Could Oak Island’s 1704 Stone Rock been a Remembrance for the Deerfield Massacre?

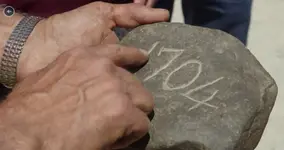

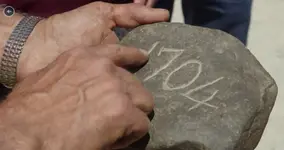

Robert Restall recovered a stone near Smith’s Cove, Oak Island, a stone with the engravings

“1704” scratched on it.

Like... San Antonio’s call

“Remember the Alamo” could this Stone have been left on the shores of Acadia to mark the terrible occurrences that took place at Deerfield,

Massachusetts,in

“1704”?

In 1702, with the outbreak of

Queen Anne's War, New England colonists had taken prisoner a successful French

pirate,

Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste.

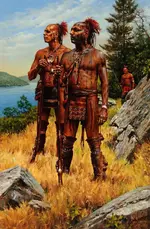

To gain his return, the French governor of Canada planned to raid the settlement of Deerfield, in alliance with the

Mohawk of the

Iroquois,

Abenaki from northeast New England and the Pocumtuc.

Their intent was to capture a prisoner of equal value to the Pirate Baptiste for exchange.

The French Raiding Party captured Deerfield, along with capturing the Reverend John Williams (a prominent man in the community) and more than 100 other English settlers.

“On the night of 28 February 1704, approximately 300 French and Indian soldiers took 112 citizens captive, besides killing a total of 56 men, women and children, including two of Williams' children (six-year-old son John Jr., and six-week-old daughter Jerushah) and his African slave Parthena.

The raiding party marched the Williams and other families on a cruel trek of 300 miles (480 km) over winter landscape to Canada.

On route to Quebec, a Mohawk killed Williams' wife after she fell while trying to cross a creek, along with Frank, another African slave.

Others of the most vulnerable older and youngest people died, some at the hands of Indians who judged them unable to go on.

Williams remained steadfast and encouraged the other captives with prayer and scripture along their journey to Quebec.

The large party had seven weeks of hard overland travel to reach

Fort Chambly.”

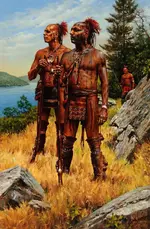

The Indian contingent included 200

Abenaki,

Iroquois,

Wyandot, and

Pocumtuc, some of whom sought revenge for incidents that had taken place years earlier.

These were joined by another 30 to 40

Pennacook led by the sachem

Wattanummon.

This party moved south toward Deerfield in January and February 1704, raising the troop size to nearly 300 by the time it reached the Deerfield area in late February.

For the 112 English captives, the raid was only the beginning of their troubles.

The raiders intended to take them to Canada, a 300-mile (480 km) journey, in the middle of winter.

Many of the captives were ill-prepared for this, and the raiders were short on provisions.

A majority of the captives taken were women and children whom the French and Indian captors viewed as being more likely than adult males to successfully integrate into native communities.

The Indians consequently engaged in a common practice by killing those captives that were unable to keep up.

Williams commented on the savage cruelty of the Indian raiders and although most killings were not random or wanton, none of those killed would have needed to be killed had they not been taken in the first place.

Most (though not all) of the slain were the slow and vulnerable, who could not keep up with the party and would likely have died less quickly on route.

Only 89 of the captives survived the ordeal.

Survival chances correlated with age and gender with infants and young children faring the worst, and older children and teenagers (all 21 of whom survived the ordeal) faring the best.

Adult men fared better than adult women, especially pregnant women, and those with small children.

Williams' wife Eunice, weak after having given birth just six weeks earlier, was one of the first to be killed during the trek.

In the first few days several of the captives escaped.

The Indians had some disagreements among themselves concerning the disposition of the captives and the French Commander Hertel de Rouville gave instructions to Reverend Williams to inform the others that recaptured escapees would be tortured.

Upon the threat of this, there were no further escapes.

This threat was not an empty one, for it was known what these Indian Raiders had done to captives on other raids.

The death of family members had a profound psychological effect upon the Iroquois and the other Indian Raiders, thus they required strong measures to relieve themselves of sadness.

Essentially, they felt that they required restitution in some form or another for their dead relatives.

Grieving matriarchs petitioned the tribe’s warriors to retrieve captives for torture.

“Of all the North American Indian tribes, the seventeenth-century Iroquois are the most renowned for their cruelty towards other human beings.

Scholars know that they ruthlessly tortured captives and that they were cannibals; in the Algonquin tongue the word Mohawk actually means flesh-eater.

There is even a story that the Indians in neighboring Iroquois territory would flee their homes upon sight of just a small band of Mohawks.”

In 1704 as a response to the French Raid on Deerfield, Massachusetts,

Benjamin Church led the retaliatory raid against

Acadia (present-day

Nova Scotia).

Benjamin Church may have used Oak Island for his base while in Acadia.

That same year, Church had raided almost all of Nova Scotia, including the villages of

Grand Pré,

Pisiquid, and

Beaubassin with the burning of these Villages, Crops, and Cattle to the ground.

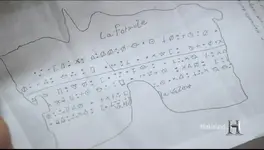

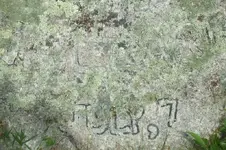

Church’s Raiding Party may have left behind on “Oak Island” the Stone Sign 1704, as a Warning and Remembrance!