sailaway

Hero Member

- Joined

- Mar 2, 2014

- Messages

- 623

- Reaction score

- 816

- Golden Thread

- 0

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Don Juan de Oñate led the first effort to colonize the region in 1598, establishing Santa Fe de Nuevo México as a province of New Spain. Under Juan de Oñate and his son, the capital of the province was the settlement of San Juan de los Caballeros north of Santa Fe near modern Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo. New Mexico's second Spanish governor, Don Pedro de Peralta, however, founded a new city at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in 1607, which he called La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís, the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi. In 1610, he made it the capital of the province, which it has almost constantly remained,[7] making it the oldest state capital in the United States.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santa_Fe,_New_Mexico

deducer, I take it you are in the same boat as Gene Botts and may even be him by the sounds of your investigation. Gene spent more than thirty years of his life as a federal criminal investigator. Writes for Deasert USA and claims the stone Maps are Fakes. http://www.desertusa.com/mag02/sep/per_stone.html

Peralta arrived in Mexico City during the winter of 1608–09 following his university studies in Spain. In March 1609 the viceroy of Mexico appointed him to the post of governor of New Mexico; and, from April to October of that year, Peralta organized an expedition to that province. He evidently reached the colony’s San Gabriel settlement, which had served as the colonial capital, by the following spring. He then moved the capital to another settlement, which became known as Santa Fe.

Peralta’s authority as governor of New Mexico was challenged by the Franciscan missionaries. In 1612 one of the missionaries, Fray Isidrio de Ordoñez, declared Peralta a “schismatic heretic” and proclaimed that he was excommunicated. A short time thereafter, Peralta was arrested and was imprisoned for almost a year, until he sent word of his situation to the viceroy, who ordered his release.

Peralta continued to serve the Spanish monarchy in the Americas, first as lieutenant commander of the Pacific seaport of Acapulco and then as alcalde of Mexico City’s royal warehouse, 1621–22. In 1637 he traveled to Caracas, Venezuela, where he married and entered a commercial enterprise. From 1644 to 1652 Peralta served as auditor and, later, as treasurer of the royal treasury in Caracas. He returned to Spain in the latter year, after sustaining injuries from residents who resented his attempts to collect debts owed to the monarchy. He resigned his commission in 1654 and lived in retirement in Madrid until his death.

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/450991/Pedro-de-Peralta

Things I noticed that seem to relate to the Peralta stones:Don Pedro de Peralta was a bachelor of canon law. A report of possessions found in his house after his arrest includes a law book. Peralto was appointed governor of New Mexico by the Viceroy, Luis de Velasco, marqués de Salinas on 31 March 1609, shortly after Peralta had arrived from Spain. Juan de Oñate had asked Velasco for compensation for his efforts in New Mexico, and asked that his son Christóbal be allowed to succeed him. Valasco replied that he had named Peralta as governor, and that Onate should hand over to him when he arrived at the Rio Grande and should then return with his son to Mexico City without delay. An expedition with supplies and reinforcements left for the north late in 1609. Peralta reached the capital, La Villa de San Gabriel, early in 1610. He was met by Oñate, who left for the south in early February to face charges of maladministration. Peralta brought twelve soldiers and eight Franciscan priests with him. His instructions included searching for the Straits of Anián,[ on which he should establish a secure port.

San Gabriel was remote from the main Pueblo Indian population centers. Juan de Oñate had planned to move the capital south to the Santa Fe River valley. Peralta selected a defensible site with ample available land and a good water supply for the town, which he called Santa Fe. He and his surveyor laid out the town, including the districts, house and garden plots and the Santa Fe Plaza for the government buildings. These included the governor's headquarters, government offices, a jail, arsenal and a chapel. On completion, the plaza could hold "1,000 people, 5000 head of sheep, 400 head of horses, and 300 head of cattle without crowding." The palace was built for defense with three-foot-thick adobe walls. The Palace of the Governors is now the oldest continuously occupied building in the United States, and as of 1999 housed the Museum of New Mexico.

The church assumed that the main objective in New Mexico was to convert the Indians, and the civil power existed only in order to provide protection and to support this goal. As chief magistrate and head of the army, the governor had equal powers but different objectives, so clashes were inevitable. The church argued that the friars had a duty to protect the Indians from abuses by the military and civilians. Perhaps to weaken the church position, Peralta issued strict regulations that imposed imprisonment for ten days by the civil authority for any Spaniard found guilty of abusing an Indian worker. A fine was also payable to the victim. This resulted in some incidents where Pueblos deliberately provoked violence in order to earn the fine.

Fray Isidro de Ordóñez, who had twice before been in New Mexico, arrived with the supply train in 1612 as the leader of nine Franciscan friars. When he reached the southernmost mission at Sandia Pueblo, he produced a document that apparently made him Father Commissary, or head of the church in New Mexico, although later the document was said to be a forgery. In Santa Fe, despite Peralta's protests, Ordóñez proclaimed that any soldier or colonist could leave if they wanted to. Ordóñez also accused Peralta of underfeeding the natives who were working on the construction of Santa Fe. The struggle for power intensified, and in May 1613 Ordonez excommunicated Peralta, posting a notice announcing this on the doors of the Santa Fe church.

On 12 August 1613 Ordóñez and his followers arrested Peralta and had him chained and imprisoned in the mission of Neustra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) at Sandia. His jailer was Fray Esteban de Perea, who disapproved but obeyed. Ordóñez assumed full civil as well as religious power in New Mexico until a new temporal governor, don Bernardino de Ceballos, arrived in New Mexico in the spring of 1614. Peralta was not allowed to leave until November 1614, after Ordóñez and the new governor had taken most of his possessions. This was the start of long-running disputes between the friars and the secular administration, which later became so violent that in 1620 the King himself had to intervene, taking the side of his governors.

Peralta returned to Mexico City and told his version of the dispute with Ordóñez. The Mexican Inquisition eventually ordered Ordóñez to return to Mexico City, and reprimanded him. Peralta was vindicated. Shortly afterwards, he was appointed alcalde mayor of the port of Acapulco. Peralta moved to Caracas, in what is now Venezuela, where he served as an official in the royal treasury the 1640s and early 1650s. Pedro de Peralta died in 1666.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_de_Peralta

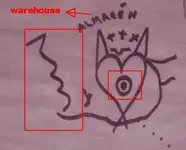

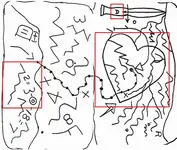

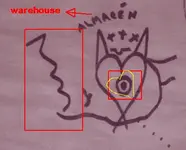

1. Pedro is on the flank of the horse

2. Santa Fe was founded by Don Pedro de Peralta and Santa Fe is on the Peralta Stones

3. Don was the title of Pedro given to him by the King of Spain and Don is on the Peralta Stones

4. Don Pedro Peralta was replaced by Ceballos (different spelling but ?) and the Peralta Stones have on them Cobollo

5. Don Pedro was jailed by the Church

6. Don Pedro de Peralta served as an official in the treasury and he had a grudge against the church and would be hard on those padre's who were mining

The Peralta Stones have no connection to Don Pedro de Peralta? Even if the connection was that he was the one whom they were convinced that they needed to hide the treasure from?

Last edited: