Law

A body of rules of conduct of binding legal force and effect, prescribed, recognized, and enforced by controlling authority.

In U.S. law, the word

law refers to any rule that if broken subjects a party to criminal punishment or civil liability. Laws in the United States are made by federal, state, and local legislatures, judges, the president, state governors, and administrative agencies.

Law in the United States is a mosaic of statutes, treaties, case law,

Administrative Agency regulations, executive orders, and local laws. U.S. law can be bewildering because the laws of the various jurisdictions—federal, state, and local—are sometimes in conflict. Moreover, U.S. law is not static. New laws are regularly introduced, old laws are repealed, and existing laws are modified, so the precise definition of a particular law may be different in the future from what it is today.

The U.S. Constitution

The highest law in the United States is the U.S. Constitution. No state or federal law may contradict any provision in the Constitution. In a sense the federal Constitution is a collection of inviolable statutes. It can be altered only by amendment. Amendments pass after they are approved by two-thirds of both houses of Congress or after petition by two-thirds of the state legislatures. Amendments are then ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures or by conventions in three-fourths of the states. Upon ratification, the amendment becomes part of the Constitution.

Beneath the federal Constitution lies a vast body of other laws, including federal statutes, treaties, court decisions, agency regulations, and executive orders, and state constitutions, statutes, court decisions, agency regulations, and executive orders.

Statutes and Treaties

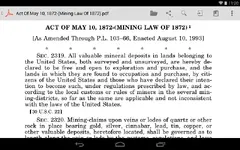

After the federal Constitution, the highest laws are written laws, or statutes, passed by elected federal lawmakers. States have their own constitution and statutes.

Federal laws generally involve matters that concern the entire country. State laws generally do not reach beyond the borders of the state. Under Article VI, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution, federal laws have supremacy over state and local laws. This means that when a state or local law conflicts with a federal law, the federal law prevails.

Federal statutes are passed by Congress and signed into law by the president. State statutes are passed by state legislatures and approved by the governor. If a president or governor vetoes, or rejects, a proposed law, the legislature may override the

Veto if at least two-thirds of the members of each house of the legislature vote for the law.

Statutes are contained in statutory codes at the federal and state levels. These statutory codes are available in many public libraries, in law libraries, and in some government buildings, such as city halls and courthouses. They are also available on the World Wide Web. For example, the statutory codes that are in effect in the state of Michigan can be accessed at <http://www.michigan.gov/orr>. A researcher may access the United States Code, which is the compilation of all federal laws, at <http://uscode.house.gov>. The site is maintained by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives.

On the federal level, the president has the power to enter into treaties, with the advice and consent of Congress. Treaties are agreements with sovereign nations concerning a wide range of topics such as environmental protection and the manufacture of nuclear missiles. A treaty does not become law until it is approved by two-thirds of the U.S. Senate. Most treaties are concerned with the actions of government employees, but treaties also apply to private citizens.

Case Law

Statutes are the primary source of law, and the power to enact statutes is reserved to elected lawmakers. However, judicial decisions also have the force of law. Statutes do not cover every conceivable case, and even when a statute does control a case, the courts may need to interpret it. Judicial decisions are known collectively as case law. A judicial decision legally binds the parties in the case, and also may serve as a law in the same prospective sense as does a statute. In other words, a judicial decision determines the outcome of the particular case, and also may regulate future conduct of all persons within the jurisdiction of the court.

The opinions of courts, taken together, comprise the

Common Law. When there is no statute specifically addressing a legal dispute, courts look to prior cases for guidance. The issues, reasoning, and holdings of prior cases guide courts in settling similar disputes. A prior opinion or collection of opinions on a particular legal issue is known as precedent, and courts generally follow precedent, if any, when deciding cases. Breaking with precedent may be justified when circumstances or attitudes have changed, but following precedent is the norm. This gives the common law a certain predictability and consistency. The common law often controls civil matters, such as contract disputes and personal injury cases (torts). Almost all criminal laws are statutory, so common law principles are rarely applied in criminal cases.

Sometimes courts hear challenges to statutes or regulations based on constitutional grounds. Courts can make law by striking down part or all of a particular piece of legislation. The Supreme Court has the power to make law binding throughout the country on federal constitutional issues. The highest court in each state has the same power to interpret the state constitution and to issue holdings that have the force of law.

Occasionally courts create new law by departing from existing precedent or by issuing a decision in a case involving novel issues, called a case of first impression. If legislators disagree with the decision, they may nullify the holding by passing a new statute. However, if the court believes that the new statute violates a constitutional provision, it may strike down all or part of the new law. If courts and lawmakers are at odds, the precise law on a certain topic can change over and over.

Common-Law Courts

Courts of law are a fundamental part of the U.S. judicial system. The U.S. Constitution and all state constitutions recognize a judicial branch of government that is charged with adjudicating disputes. Beginning in the 1990s, vigilante organizations challenged the judicial system by establishing their own so-called common-law courts. By 1996 these common-law courts existed in more than 30 states. Though they have no legitimate power, being created without either constitutional or statutory authority, and in fact sometimes contravene established law.

Traditionally, common-law courts administered the

Common Law, that is, law based on prior decisions rather than statutes. These new common-law courts, however, are premised on a mixture of U.S.

Constitutional Law, English common law, and the Bible, all filtered through an often racist and anti-Semitic world view that holds the U.S. legal system to be illegitimate. These common-law courts imitate the formalities of the U.S. justice system, issuing subpoenas, making criminal indictments, and hearing cases. Most of their cases involve

Divorce decrees and foreclosure actions. Many of the persons on the courts or seeking their assistance are in dire financial circumstances. They wish to prevent the loss of their property by having a common-law court declare them free of the loans they have secured from banks.

Though common-law courts appeared to be merely a symbolic attempt by extremists to assert their political legitimacy, the actions of some of them led to prosecution for criminal conspiracy. Common-law courts have issued arrest warrants for judges and prosecutors in Montana and Idaho and have threatened sheriffs who refused to follow their instructions. In 1994 the Garfield County, Montana, prosecutor charged members of a common-law court with criminal syndicalism, for advocating violence against public officials. One court member was sentenced to ten years in prison, and others received shorter sentences.

When researching a legal issue, it is helpful to consult relevant case law. The researcher first finds the relevant annotated statutes, and then reads the cases that are listed under the statutes. Reading case law helps the researcher understand how the courts interpret statutes, and also how the courts analyze related issues that are not covered in the statutes. Volumes of case law can be found in some public libraries, in law libraries, in courthouses, and in state government buildings such as statehouses and state libraries. Case law research can also be conducted using the

Internet. For example, Cornell University's online Legal Information Institute (<http://www.law.cornell.edu>) offers recent and historic U.S. Supreme Court decisions, as well as recent New York appeals decisions.

Agency Regulations and Executive Orders

Administrative agencies may also create laws. The federal and state constitutions implicitly give the legislatures the power to create administrative agencies. Administrative agencies are necessary because lawmakers often lack detailed knowledge about important issues, and they need experts to manage the regulation of complex subjects. On the federal level, for example, the Department of the Interior was created by Congress to manage the nation's natural resources. In creating the agency, Congress gave it power to promulgate regulations concerning the use and protection of natural resources.

Administrative agency regulations have the force of law if they have a binding effect on the rights and duties of persons. For example,

Interior Department regulations that prohibit mining or logging in certain areas of the country are considered law, even though they are not formulated by an elected official or judge. Federal administrative agency rules are approved by Congress, so ultimately they are a product of the will of elected officials. Similarly, on the state and local levels, an administrative agency may promulgate rules that have the force of law, but only at the pleasure of the elected lawmakers that created the agency. If an agency seeks to change a regulation, it must, in most cases, inform the public of its intentions and provide the public with an opportunity to voice concerns at a public meeting.

Not all agency regulations have the force of law. Agency rules that merely interpret other rules, state policy, or govern organization, procedure, and practice need not be obeyed by parties outside the agency.

Some administrative agencies have

Quasi-Judicial powers. That is, they have limited authority to hear disputes and make binding decisions on matters relevant to the agency. For example, the

Health and Human Services Department (HHS) has a court with authority to hear cases concerning actions by the HHS, such as the denial of

Social Security benefits. An administrative law judge (ALJ) presides over the court, and appeals from ALJ decisions can be taken to an HHS appeals council. If an administrative agency has quasi-judicial powers, decisions made by the ALJ and boards of appeals have the force of law.

The quickest way to uncover information about state agency regulations is to search the World Wide Web. Most state agencies maintain a comprehensive website. Each state's

Secretary of State can also be accessed on the Web. Most agencies are named according to their area of concern. For example, a department of

Gaming is concerned with gambling, and a department of fish, game, and wildlife is concerned with issues related to hunting and wildlife conservation.

Executive orders are issued to interpret, implement, or administer laws. On the federal level, executive orders are issued by the president or by another

Executive Branch official under the president's direction. Executive orders range from commands for detailed changes in federal administrative agency procedures to commands for military action. To have the force of law, a federal

Executive Order must be published in the

Federal Register, the official government publication of executive orders and federal administrative agency regulations. On the state level, governors have similar authority to make laws concerning state administrative agencies and state military personnel.

Local Laws

Counties, cities, and towns also have the authority to make laws. Local laws are issued by elected lawmakers and local administrative agencies. Local laws cannot conflict with state or federal laws. Decisions by local courts generally operate as law insofar as they apply to the participants in the case. To a lesser extent, local court decisions may have a prospective effect. That is, a local court decision can operate as precedent, but only in cases brought within the same jurisdiction. For example, a decision by a court in Green County may affect future court cases in Green County, but it has no bearing on the law in any other county. Local laws can be found in local courthouses, in local libraries, and in state government libraries. Local laws may also be accessed via the World Wide Web.

Cross-references

Administrative Law and Procedure;

Civil Law;

Congress of the United States;

Constitutional Amendment;

Constitution of the United States;

Court Opinion;

Criminal Law;

Equity;

Federalism;

Federal Register;

Judicial Review;

Private Law;

Public Law;

Stare Decisis.

West's Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.