by Donald T. Garate

Arizona is a Basque word with a very straightforward meaning:

Ariz - oak tree

on - good

a - the

The Good Oak Tree

First because of a myth that there was a Real de Minas, or a Royal Mining Camp, or District, named “Arizonac” that has been perpetuated in the secondary literature as historical fact, he theorized that the name might come from the Basque arri (rock) and ona (good) with the letter “c” added onto the end of the word to make it plural, as is customary in the Basque language. In short, this would provide a possible meaning of “the good rocks,” describing a mythical mining district in which silver was being extracted from the rocks.

Secondly, however, he suggested that the name very possibly means “the good oaks,” coming from the two Basque words aritz (oak) and ona (good) with the pluralizing letter “c” added at the end. Although any speaker of the Basque language, anywhere in the world would recognize aritz onak to mean “the good oak trees,” Dr. Douglass did not make it clear for the non-speaker that is a modern spelling of the word which came about largely as a result of the Euskara Batua, or Unified Basque Language effort of this century to unify all the Basque dialects and establish a uniform spelling system for writing the language. Although he gave examples of Basque surnames that use the word “oak,” such as Ariz (oak), Ariza (the oak), Arizandi (big oak), Arizmendi (oak mountain), and Arizmendiarrieta (the rocky, oak covered mountains), many readers did not understand that there is a modern spelling, aritz, and a universal historic spelling of ariz or aris. One other surname that should be added to this list is that of Arizona. Though not common, the fact that it was used as a surname is evidenced by the appointment of Fr. Antonio de Arizona as calificador (book examiner) for the office of the inquisition in Mexico City in 1721.

It is necessary to give a brief history of the discovery of the planchas de plata for those who are not familiar with the story, and to review the subject and make corrections in the historical inaccuracies for those who are. To accomplish all of the foregoing, this article will use

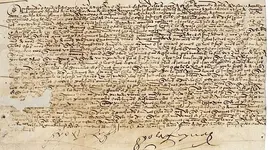

the original documents of the 1736 silver discovery - something that has not been done before. Everyone else who has written about the subject has either quoted secondary sources for their information and interpretation, or, if they have used the Spanish documents, they have used copies (or copies of copies) of the original documents which were written by the men who were there. Although Spanish escribanos generally copied documents closely and accurately, even an accurate transcription does not tell the reader who's handwriting the original was in or what spelling ability the person had. Copies often correct what the scribe interpreted to be grammatical errors or misspellings in the original, which, when dealing in the subject of ethnic or language differences can have a profound effect on our understanding of the subject. And, as will be shown in the case of Prudhom's map, scribes and cartographers of a different era sometimes added their own interpretation to someone else=s work, often for purposes known only to themselves or those for whom they were working

The story begins in October of 1736. At that time, the most northwestern settlement in Sonora that had a large enough Spanish population to be considered a village was a newly established Real de Minas, or Royal Mining Camp, called Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Concepción del Agua Caliente.

In todays world Agua Caliente lies ten air miles south of the international border between Arizona and Sonora. Although it is the same place as described in the 1736 documents, the patron name of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception was long ago dropped from the name. The tiny settlement of a few ranch houses in the narrow Planchas de Plata Canyon is eighteen air miles southwest down the mountain from Nogales, Sonora, across a precipitous system of rocky, oak covered canyons and ridges. At the time of this writing, as in 1736, a stones throw from Agua Caliente in La Cienega Canyon near its confluence with the Planchas de Plata, is what todays English speaking cowboy would call a line camp. It was, and is, known as Arizona.

It would appear that there were several people living at Arizona and probably two or three times as many at Agua Caliente in 1736. These were mostly prospectors who were scouring the mountains to the north for mineral deposits and it is clear from their statements that they made no clear cut distinction as to where Agua Caliente ended and Arizona began.

A little over twenty air miles northeast of the Agua Caliente and Arizona settlements (about four miles due east of present-day Nogales) across this rugged and harsh, remote mountainous terrain was an older and larger Spanish settlement. Located in the San Luis and the Upper Santa Cruz River Valleys, which today straddle the international border, were two missions, Guevavi and Suamca, a number of Spanish ranches, and numerous Piman rancherías. Though the majority of the 1736 Spanish ranches were in the San Luis Valley in present-day Sonora, at least two, the Guevavi Ranch and the San Mateo Ranch were located in the upper Santa Cruz Valley in what is today the State of Arizona.

It was on a hill almost equidistant between these Spanish settlements of the San Luis Valley and Agua Caliente/Arizona that a Yaqui Indian prospector, Antonio Siraumea, stumbled onto some large chunks of almost pure silver. Since he was living at Agua Caliente, he returned home and took some of his children back up to the site to help look for more pieces of the precious metal. News of the discovery, of course, spread like wildfire. The first wealth seekers on the scene were residents of Agua Caliente. Francisco de Longoria filed the first, and what appears to be the only legal mining claim at the site of the discovery before the authorities arrived on the scene and put a stop to the digging. Others, illegally and without registering, scooped up the pieces of silver which were lying on or near the surface of the ground. José Fermín de Almazan discovered a single slab that weighed over one hundred arrobas, or roughly one and a quarter tons. He chipped some pieces off of the gigantic chunk and rode over the mountain to Diego Romeros ranch in the San Luis Valley, where he exchanged the silver for trade goods. Word of the marvelous discovery spread from there all over Sonora. Practically over night a frenzied silver rush was on.

Ninety miles away at the village of Bacanuchi where he was conducting court on Tuesday, November 13, 1736, Justicia Mayor, or Chief Justice of Sonora, Juan Bautista de Anza heard of the unusual discovery. Anza was also Capitán Vitalicio, or Captain for Life of the Fronteras Presidio and father of the more famous Juan Bautista de Anza who, in the next generation, lead colonists to San Francisco, orchestrated the Pecos peace treaty with the Comanches, and was governor of New Mexico for ten years. The younger Juan Bautista was four months and six days old when his father received word of the silver strike. As the King's official representative to make decisions in such matters, the senior Anza immediately set to work. Antonio Siraumea, who claimed his rights as the first discoverer, wanted a decision that would force the others who arrived later on the scene, to pay him a share of all the silver they were able to find. However, there were more weighty decisions that needed to be made. Everything, that Anza had been told about the nature of the silver led him to believe that it was somebody's buried treasure or a clandestine smelting operation, and not a natural vein of silver. If that was the case, all of the precious metal would belong to the King. On the other hand, if it was a vein, mining claims must be properly filed and the King's fifth extracted from the total.

Captain Anza obtained opinions from three Jesuit priests, the best educated and most knowledgeable of the law of all the citizens on the frontier.20 With their statements in hand he set out for the discovery site, traveling first via his Guevavi Ranch where he enlisted the help of his ranch foreman and cousin by marriage, Manuel José de Sosa. When the two men and what was evidently a fairly sizeable soldier escort arrived at the scene on November 20, they immediately began taking depositions. Anza named the site after his patron saint, San Antonio de Padua.

Santiago Ruiz de Ael, a merchant who was on the scene selling food and other supplies from a heavily laden pack string he had brought over 150 miles from Motepore, estimated that there were four hundred people there scratching in the earth, searching for more of the bolas y planchas. Whatever the numbers may have been, Anza quickly put a stop to their unregistered and illegal prospecting. He placed an embargo on the silver until such time as a determination could be made concerning how much of it belonged to the King. He put a soldier guard around the site to make sure that everyone abided by his orders. Then he did what seems to have brought Arizona to

the forefront and left San Antonio de Padua in obscurity. He rode the twelve miles down the canyon to Bernardo de Urrea's house where he spent from November 28 to Decemeber 3 dictating and signing dispatches and orders, and impounding all the silver that had been found. Urrea was his teniente, or deputy justice over the Realito of Agua Caliente and its district, but his house was located, not in the real, but in el puesto, the place or residence called Arizona.

Thus sixteen important documents dictated to Sosa and signed by Anza, were written and dated at Bernardo de Urrea's house in el puesto del Arizona. Statements from other individuals were also taken there. It was at Urrea's house at Arizona that Santiago Ruiz de Ael, the merchant of Motepore, first filed his petition with Anza to get his impounded silver back. Over the course of the next few years in far away locations like Mexico city, or even other areas of Sonora, the place called Arizona began to be confused with the place called San Antonio de Padua. Arizona soon began to take on a much larger than life image in the eyes of those who had never been there.

Anza appointed a couple of miners to take samples and assay the silver. Just before he left Arizona to ride back up to San Antonio, as he was about to mount his horse, he was presented with a petition from fifteen residents of the Real of Agua Caliente, asking that the embargo be lifted as soon as possible so they could have their silver back. At the site of the discovery, he tightened up security, examined Almazan's one-ton chunk more closely, dictated more orders, and then continued on up and across the mountains to the San Luis Valley. There, at Nicolas Romero's Santa Barbara Ranch, between December 5 and 20 he dictated and received more dispatches. Orders were sent to his deputies throughout Sonora, to confiscate and impound the silver wherever it had been taken in trade. On December 20, 1736, having been informed that everyone had vacated the site of the discovery, and leaving Urrea in charge of its security, Anza headed back to Fronteras to be with his family during the celebration of the “Holy Days.”

In January when the silver had all been impounded, Anza dispatched Sosa to Mexico city with copies of all the letters, orders, dispatches, petitions, etc. Two court cases also developed simultaneously. Ruiz de Ael petitioned the Real Audiencia through appointed lawyers in Mexico City to order Anza to return the impounded silver that he had taken in trade, a case which he lost.

José de Meza and Francisco de Longoria filed suit with the Audiencia in Guadalajara against Sonora's Alcalde Mayor, Francisco de Garrastegui. This came about because Garrastegui had previously opened the borders of Sonora to Anza for further exploration. Now with the magnificent silver discovery on the very northern border, it seemed eminent that the Viceroy would approve such an exploration party. Meza, who was obviously the instigator and main pusher of the suit, sought to block Anza from receiving the commission that he might obtain the honor for himself and carry out the exploration as soon as his impounded silver was returned. He also lost his case when it was pointed out by the court that, He was not the first discoverer of silver, as he claimed and Just because he had fought valiantly while his family was being killed by Apaches did not qualify him to be commissioned a captain and lead an important exploratory expedition.

Investigation of the nature of the planchas de plata now shifted to Mexico City. Fiscal Ambrosio Melgarejo, state attorney, believed that the silver was a treasure, hidden there by some ancient people. Consequently, it should all belong to the King. The Fiscal's report was sent to the Real Acuerdo for their opinion. They reviewed it and five of the six members leaned toward the treasure theory but felt there should be further investigation. The sixth and dissenting member offered the opinion that the silver must have come from a natural vein. Viceroy Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta, Archbishop of Mexico, followed the advice of the five and ordered further assays and studies.

After reviewing all the opinions and studies and Ruiz de Ael=s court case, Vizarrón sent orders to Anza on June 8, 1737 “...to go immediately, with the most expert miners of those regions, to survey the make-up and quality of the land in the canyon where the silver was found...” and determine exactly how the silver chunks had been produced. Anza acknowledged receipt of the order on July 19, but estimated it would take him three weeks to gather a group of expert miners at the site because they were all fifty or sixty leagues (roughly 150 miles) away. In time, he and five of the leading miners of Sonora gathered at San Antonio de Padua on August 8, 1737. The chosen “experts” unanimously concurred that the silver had come from several natural veins. Anza scoured the surrounding hills in search of any evidence of covert smelting operations, finding nothing. He interviewed Pima Indians from Saric but they had no knowledge of the silver, claiming that they never entered the remote area because of its inaccessibility and ever-present Apache danger.

Captain Anza then proceeded to Agua Caliente where he lifted the embargo and returned everyone's silver to them, minus the King's fifth and enough for expenses that had been incurred.

Turning back once again to the discovery site, he surveyed a 160-vara (1440 square foot) claim and registered it to Antonio Siraumea. A three hundred pound piece of the one-ton plancha was sawed off to be transported to Mexico City for further studies. Almazan was to receive payment for it as it now truly belonged to him. By the end of September Anza was back at Fronteras where he compiled his final report on the matter to the Viceroy.

One year after the initial discovery, several miners were now legally working the area and some new silver had been discovered. The three hundred-pound piece of silver was on its way to Mexico City, where it would arrive by March of 1738. The original prospectors had been given most of their impounded silver back and everyone on the frontier seemed content. Fiscal Melgarejo, however, was furious! He ranted about Anza's and the five mining experts' incompetency and the inconsistencies between their statements in 1737 as compared to the statements Anza had made in November of 1736. He stopped just short of calling Viceroy Vizarrón, himself, incompetent and demanded that “true” experts be sent to the site for further study.

http://www.nps.gov/tuma/historyculture/upload/TUMA-Arizona-article.pdf

! In trying to decide on a 'reading plan' for this mystery, I decided to start with the etymology. Found this article by Donald Garate with the NPS, wherin he makes some interesting statements which I copy here:

! In trying to decide on a 'reading plan' for this mystery, I decided to start with the etymology. Found this article by Donald Garate with the NPS, wherin he makes some interesting statements which I copy here:

,

,