Story from Desert Magazine 1938 June (Pages 6 through eight). Other than Kenworthy in the 70's (out of no-where literarlly) I wanted to find other people who had found "certain kinds of rock art designating locations". Well, this is some confirmation some 40+ years before Kenworthy. (Pictures to follow).

Hidden Valley --- Temple of Mystery

You have to crawl through a narrow tunnel to reach the valley."

The speaker gazed reflec-tively at the campfire and continued, "I reckon it's pretty safe to go inthere nowadays, but back in the 70 s a feller that wanted to remain healthy gave the valley a wide berth!" We had camped for the night at Quail Springs in the Joshua Tree National Monument of Southern California. In the little group seated around our campfire was one of those hopeful patriarchs of the desert whose strike is always just one day ahead—tomorrow, and tomorrow. From tales fanciful and real of lost mines, bonanzastrikes and frontier justice, the talk turned to cattle, cattle rustlers, and to the activities of the thieving fraternity in the area in which we were then camped.

Although it was overlooked by the Forty-Niners during the first gold rush, the territory which comprises the newly created Joshua Tree playground drew many gold seekers during the following years. After the miners had dispersed to other fields, cattlemen appeared on the scene. Galleta grass grew in abundance. The water problem was solved by building

reservoirs or "tanks" to catch the rainfall. As the cattle operations spread out it was inevitable that the gentry whose livelihood was gained by extra - legal methods should make their entry. Inaccessibility of the region made it ideal for their calling. Here stolen livestock could be kept from the eyes of the law until it could be driven across the Arizona borderand sold.

"I said that you have to crawl through a tunnel to reach the valley," the old prospector resumed, "but when those rustler fellers were active they built a regular stairway for their cattle on the south side of the valley. There is a steep wash cut through the rocky walls from the floor of the valley to the desert outside. When they were moving their stolen plunder those rascals would move enough boulders to make it passable, and then roll them back into place."

This was my introduction to Hidden Valley. The rustlers are no more. Time and the elements have removed all traces of the precipitous trail over which they drove their stolen cattle, but a narrow tunnel still affords access to one of the most picturesque spots in the Southwest.

From the huge stone figure of a bird which appears to stand guard over the outside entrance, to the granite bull high upon a rocky abutment at the western end of the valley, a fantastic array of stone figures meets the eye of the visitor.

Foremost among these is the "Trojan," a grim-visaged resemblance to a warrior of ancient Troy, which adorns the inside wall at the right of the entrance. A few feet away another figure appears in the making, crude as yet, but sharply enough defined as an iceman with a block of ice on his shoulder. Because of its perfect outline and the commanding position it occupies, the stone bull presents perhaps the most startling figure in the area and, incidentally, a challenge to those who take pride in their ability as mountain climbers. Access to the figure is not easy. The way leads over huge boulders with spaces up to several feet between them. But if one has the sure-footedness of a mountain

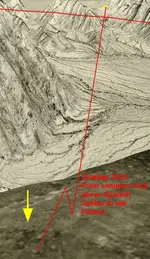

sheep, he should be able to reach the top without much difficulty. Only from such a vantage point as the stone bull affords can the remoteness of Hidden Valley and its advantages as a rendezvous for early-day cattle rustlers be fully appreciated. Not more than a few hundred feet apart, the two piles of granite boulders comprising the walls of the valley extend parallel for a distance of approximately one-half mile, then convergeto form the western end.

So deceptive are these walls when viewed from the outside that they appear as a single ridge of granite. Attesting this fact is the experience of a friend of the writer, who ignoring definite directions as to how to reach Hidden Valley, came back with the vehement assertion that no such valley existed! He had viewed both walls from

the outside and had decided that nothing larger than a kangaroo rat could pass between them.

The region surrounding Hidden Valley has been a fertile field for archeological explorations for the past decade, but the valley has been overlooked. That it may have been inhabited by some aboriginal race in times past is indicated by the fragmentary pieces of pottery which have been found on the floor of the valley. Of added significance is the fact that in the area surrounding the valley crude thick pottery has been found along with the thin highly decorated type, while only pieces of the latter have been found in

the valley. Archeologists who have worked in the surrounding territory are not sure whether these two types of pottery mark definite and separate periods in the prehistoric life of this region or the colored earthenware was brought in through barter with tribesmen residing at distant points.

Seeking to learn more about the aboriginal inhabitants of Hidden Valley, I engaged one of the numerous Indians who drift down into Banning from the reservation to accompany me into the valley. Old John, as he was known, came well recommended. He could read petroglyphs, it was said, and even determine the tribe of Indians that occupied certain

campsites. Upon being shown some writings incised in the rocks adjacent to Hidden Valley he made no comment, but over pieces of thick pottery he grew quite voluble. They were, he indicated, left by members of his tribe, the Cahuillas. After entering Hidden Valley, Old John became sullen and morose. A fragment of highly decorated pottery brought forth

the cryptic remark, "Injun no live here." Undismayed, I led him to where some petroglyphic figures showed faintly through a covering of moss.

Again the curt re-ply, "Injun no live here." Whether the failure of my guide to reveal the history of the valley was due to some ancestral taboo, or to just plain ignorance of his surroundings, I was not able to determine. If the former, it may be affirmed that Old John did nobly in keeping the taboo intact.

For those lovers of the desert to whom the beaten path has become commonplace, and who feel that there are no new trails, a trip into Hidden Valley should prove a revelation. With its bizarre examples of Nature's handiwork, its thrilling possibilities of additional discoveries, and the restful isolation that its location affords, the valley will undoubtedly take its place as one of the most attractive spots in the whole desert area.

Hidden Valley may be reached by following the Quail Springs road where it branches off to the right from the Twenty- Nine Palms highway, 29.2 miles from U. S. highway 99. Six and three-tenths miles beyond Quail Springs the road forks to the left to join the Twenty-Nine Palms to Mecca road. Continue along that road seven-tenths of a mile where the car may be parked and the rest of the journey made afoot. The tunnel entrance may be found approximately 600 feet from the road.