DIGGING UP EVIDENCE OF 400-YEAR-OLD GLOBAL TRADE AND WEALTH

Largest 17th Century Bead Repository Found in Coastal Georgia

First Evidence of Spanish Beadmaking

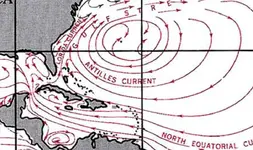

French and Chinese blue glass, Dutch layered glass, Baltic amber: roughly 70,000 beads manufactured all over the world have been excavated at one of the Spanish empire's remotest outposts, the Santa Catalina de Guale Mission. The beads were found as part of an extensive, ongoing research project led by a team of scientists from the American Museum of Natural History on St. Catherines Island off the coast of Georgia. Comprising the largest repository ever from Spanish Florida, the beads enlighten archaeologists about past trade routes and provide clues to the social structure and wealth of the people.

"This is the northernmost outpost of the Spanish empire, but we see evidence of ancient trade routes from China via Manila's galleons to Mexico and Spain," says Lorann Pendleton, Director of the Archaeology Laboratory at the Museum. "We also have found perhaps the first evidence of Spanish beadmaking, along with beads from the main centers of Italy, France, and the Netherlands."

The mission of Santa Catalina de Guale was inhabited by Franciscan missionaries and local people for most of the 17th century. The mission was a major source of grain for Spanish Florida and a provincial capital until1680, when the mission was abandoned after a British attack. Since 1974, David Hurst Thomas, Curator of Anthropology at the Museum, and colleagues have been carefully unearthing this part of the island's history. The current research is based on the complete excavation of the church's cemetery and extensive survey and excavation in other parts of the mission. Years of analysis reveal roughly 130 different types of beads on the island, and numbers of specimens per type range from one to 20,000. Most of the more common beads are of Venetian and potentially French origin, with new research suggesting that one of the most common beads of the 17th century, the Ichtucknee blue, was manufactured in France. Some of the unique beads, though, may be Spanish, Chinese, Bohemian, Indian, or Baltic in origin.

While roughly 2,000 beads were found elsewhere at the mission (such as in the convent), most were found in the cemetery under the church. These were items intentionally deposited with individuals as grave goods, and the analysis of these items shows that there were subtle temporal and spatial changes in how the cemetery was used. Most burials found with large numbers of beads appear to date to the earlier part of the mission's history (the first half of the 17th century); items found with burials that date to the latter half of the 17th century are more likely to be religious medallions and rosaries. But because almost half the beads in the cemetery were buried with a few individuals who tended to be near the altar, it is often assumed that they were of high status in the community.

"A higher number of beads were found toward the altar, and some of the highest-status individuals (by number of beads) were children," says Pendleton. "This gives us lots of information about Guale society and means that status was ascribed with birth."

Elliot Blair, graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California at Berkeley, agrees but points out that "the picture that is emerging is turning out to be much more complicated than people had thought. It's hard to say whether the presence of the beads reflects native or church hierarchies, the presence of wealthy individuals, or something else entirely. Still, this is the largest assemblage of beads ever found in a Spanish mission in La Florida, and the study of these materials has yielded considerable information about how Guale society, burial practices, and Spanish missionization changed during the 17th century."

The number of beads found on St. Catherines Island suggests that Santa Catalina de Guale was a relatively wealthy outpost. The island is fertile and was the capital of a mission province, both potential explanations for the high number of beads found when compared to other missions.

From left to right: Common cobalt blue seed bead, most likely from Venice (20,906 found); unique blue green melon bead from China; Spanish gilded oval glass bead (15 found); ichtucknee plain turquoise blue bead with white patinas now thought to be manufactured in France (one of 5,265); On top greenish blue faceted bead or charlotte from the Margariteri guild of Venice (138 found); bottom Venetian turquoise/green-blue seed bead or rocaille (5777 found); five layer chevron compound bead from the Netherlands (3 fragments); unique bead of opaque blue over transparent blue with stripes, probably from the Paternostri guild of Venice; Green Heart bugle bead with a thin clear veneer over red-orange glass over green glass from the Margariteri guild of Venice (one of 5); and a speo Green Hearts from the Paternostri Venetian guild (one of 12).

From left to right: On top French manganese black opaque bead, some created with the a speo process; bottom Spanish spherical dot-incised gilded glass bead (6 found); cut crystal, potentially manufactured in Spain because of inferior quality to known beads from France or Venice (6 found, as well as other nonglass beads of carnelian, jet and amber); On top unique yellow melon shaped bead, possibly from China; bottom Chinese wound translucent-transparent green (4 found); blown black bead with greenish-yellow dots (13 found with one burial that are potentially French); wound green faceted teardrop (unique, of unknown origin, and not found with a burial); and Spanish cross of manganese black glass decorated with white waves and light blue dots (one of 5).

American history books have long disparaged the Spanish presence in America, discounting “poor little St. Augustine” as one of the most impoverished outposts in the Spanish global community. The colonists self-characterized La Florida as a place of neglect and ruin.

For 15 years, I directed Museum excavation at this extraordinarily well-preserved 16th- and 17th-century Franciscan mission, and I can safely say that those history books are dead wrong.

The archaeology produced surprises from the very start. The church and surrounding mission buildings were well constructed and carefully laid out on a town grid. Knowing that Franciscan customs dictated that the mission cemetery be placed inside the church, we encountered the remains of more than 400 people interred there. We were shocked by the quantity and quality of the grave goods we recovered. Having excavated several burial mounds on the island—often loaded with mortuary offerings—we knew that indigenous St. Catherines Islanders had long felt that “you can take it with you” to the afterlife. The Guale people clearly continued to place grave goods with the Christian burials. We puzzled over why the Franciscan friars would permit such “heathen” customs to be practiced at Mission Santa Catalina.

As the archaeological evidence accumulated, we began to question the conventional historical wisdom.We were also startled by the remarkable artifacts we found—

gold and silver medallions, silver sacred heart rings, bells, mirrors, several complete ceramic vessels, and more than 65,000 glass trade beads. How did the mission Indians at Santa Catalina obtain some of the world’s most valuable beads, imported from Europe, China, and India? How did this tiny settlement on the Georgia coast—the so-called outpost of an impoverished outpost—become enmeshed in a global exchange network?