pegleglooker

Bronze Member

- Jun 9, 2006

- 1,857

- 238

- Detector(s) used

- ace 250

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Has anyone else heard of this  Or any comments

Or any comments  ? Oroblanco you there

? Oroblanco you there

PLL

[size=12pt]

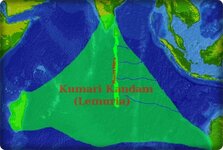

Perhaps the most popular example of Mount Shasta lore, and a legend involving the first claim by non-Native Americans for a spiritual connection with the mountain, concerns the mystical brotherhood believed to roam through jeweled corridors deep inside the mountain. According to Miesse, "In the mid-19th Century paleontologists coined the term "Lemuria" to describe a hypothetical continent, bridging the Indian Ocean, which would have explained the migration of lemurs from Madagascar to India. Lemuria was a continent which submerged and was no longer to be seen. By the late 19th Century occult theories had developed, mostly through the theosophists, that the people of this lost continent of Lemuria were highly advanced beings. The location of the folklore 'Lemuria' changed over time to include much of the Pacific Ocean. In the 1880s a Siskiyou County, California, resident named Frederick Spencer Oliver wrote A Dweller on Two Plants, or, the Dividing of the Way which described a secret city inside of Mount Shasta, and in passing mentioned Lemuria. Edgar Lucian Larkin, a writer and astronomer, wrote in 1913 an article in which he reviewed the Oliver book. In 1925 a writer by the name of Selvius wrote "Descendants of Lemuria: A Description of an Ancient Cult in America" which was published in the Mystic Triangle, Aug., 1925 and which was entirely about the mystic Lemurian village at Mount Shasta. Selvius reported that Larkin had seen the Lemurian village through a telescope. In 1931 Wisar Spenle Cerve published a widely read book entitled Lemuria: The Lost Continent of the Pacific in which the Selvius material appeared in a slightly elaborated fashion. The Lemuria-Mount Shasta legend has developed into one of Mount Shasta's most prominent legends" (1993; 136).

According to Zanger, Frederick Spencer Oliver was a Yrekan teen who claimed that his hand began to uncontrollably write a manuscript dictated to him by Phylos, a Lemurian spirit (1993). Meisse points out that Oliver's novel of spiritual fiction is "The single most important source of Mount Shasta's esoteric legends. The book contains the first published references linking Mt. Shasta to: 1) a mystical brotherhood; 2) a tunnel entrance to a secret city inside Mount Shasta; 3) Lemuria; 4) the concept of "I AM"; 5) "channeling" of ethreal spirits; 6)a panther surprise" (1993; 143). The author claims to have written most of the novel within sight of Mount Shasta, and autobiographical telling of the story from Phylos the Thibetan's point of view is an interesting twist. We have included a few pages of text from the novel, including the reference to the mystic brotherhood that lives amid "the walls, polished as by jewelers, though excavated by giants; floors carpeted with long, fleecy gray fabric that looked like fur, but was a mineral product; ledges intersected by the builders, and in their wonderful polish exhibiting veinings of gold, of silver, of green copper ores, and maculations of precious stones." (Oliver 1905; 248).

[youtube=425,350]v/OvvpcKHn3DQ&hl=en&fs=1&"[/youtube]

In 1908, Adelia H. Taffinder wrote an article, "A Fragment of the Ancient Continent of Lemuria," for the Atlantic Monthly. In her article she links the concept of Lemuria to California, and Meisse proposses that the article, "with its Theosophical teachings and extension of the Lemurian Myth to California, may have been part of the research material involved in the creation of the Mount Shasta Lemurian Myth as presented by Selvius in 1925 and Creve in 1931" (1993; 147).

Selvius' 1925 two-page article, "Decendants of Lemuria" is, according to Meisse, "the singlemost inportant document in the establishment of the modern Mt. Shasta-Lemurian myth," so we have included Selvius' full-text article. Selvius claims that Professor Edgar Lucian Larkin viewed the Lemurian site on Mount Shasta using his telescope: "Even no less a careful investigator and scientist than Prof. Edgar Lucin Larkin, for many years director of Mount Lowe Observatory, said in newspaper and magazine articles that he had seen, on many occasions, the great temple of this mystic village, while gazing through a long-distance telescope."

Although Selvius' article is the most historically interesting, Wishar Spenle Cerve's 1931 Lemuria: The Lost Continent of the Pacific is, according to Meisse, "responsible for the legend's widespread popularity" (1993; 146). Perhaps most intriging is Meisse's speculation that "it appears from the similarity of material that "Selvius" and "Cerve" were one and the same person" (1993; 145). Further muddying the waters is Edward Stul's worth claim that "Wishar Spenly Cerve" is really a letter-for-letter pseudonym for "Harve Spencer Lewis," first Imperator of the Rosicrucian Order of North and South America. Still, it is Cerve's book, published by the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, that has provided the popular description of the Lemurians as "tall, graceful, and agile," and as visitors that "would come to one of the smaller towns and trade nuggets and gold dust for some modern commodities" (250).

The idea of a lost continent (and the subsequent existence of Lemurians on Mount Shasta), quickly became widely known, though perhaps not so widely believed. In 1939, Mount Shasta botanist William Cooke was in a Cincinati library when he was asked if he "knew anything about the LeMurians." A few months later, in a Mount Shasta Herald article called "Lights on Mt. Shasta: Evidences Discounted," Cooke questions the legend that Larkin could have used a telescope to see any structures on Mount Shasta. About a year later, in another Herald article, titled "Wm. Bridge Cooke Discusses 'Lost Continent' Book," Cooke questioned the possibility of a Lemuria or Mu (1941).

Today the belief that Lemurians inhabit the mountain is still very popular, and anyone visiting the local bookstores will likely be suprised by the plethora of texts on the subject.

Or any comments

Or any comments  ? Oroblanco you there

? Oroblanco you there

PLL

[size=12pt]

The Origin of the Lemurian Legend

Perhaps the most popular example of Mount Shasta lore, and a legend involving the first claim by non-Native Americans for a spiritual connection with the mountain, concerns the mystical brotherhood believed to roam through jeweled corridors deep inside the mountain. According to Miesse, "In the mid-19th Century paleontologists coined the term "Lemuria" to describe a hypothetical continent, bridging the Indian Ocean, which would have explained the migration of lemurs from Madagascar to India. Lemuria was a continent which submerged and was no longer to be seen. By the late 19th Century occult theories had developed, mostly through the theosophists, that the people of this lost continent of Lemuria were highly advanced beings. The location of the folklore 'Lemuria' changed over time to include much of the Pacific Ocean. In the 1880s a Siskiyou County, California, resident named Frederick Spencer Oliver wrote A Dweller on Two Plants, or, the Dividing of the Way which described a secret city inside of Mount Shasta, and in passing mentioned Lemuria. Edgar Lucian Larkin, a writer and astronomer, wrote in 1913 an article in which he reviewed the Oliver book. In 1925 a writer by the name of Selvius wrote "Descendants of Lemuria: A Description of an Ancient Cult in America" which was published in the Mystic Triangle, Aug., 1925 and which was entirely about the mystic Lemurian village at Mount Shasta. Selvius reported that Larkin had seen the Lemurian village through a telescope. In 1931 Wisar Spenle Cerve published a widely read book entitled Lemuria: The Lost Continent of the Pacific in which the Selvius material appeared in a slightly elaborated fashion. The Lemuria-Mount Shasta legend has developed into one of Mount Shasta's most prominent legends" (1993; 136).

According to Zanger, Frederick Spencer Oliver was a Yrekan teen who claimed that his hand began to uncontrollably write a manuscript dictated to him by Phylos, a Lemurian spirit (1993). Meisse points out that Oliver's novel of spiritual fiction is "The single most important source of Mount Shasta's esoteric legends. The book contains the first published references linking Mt. Shasta to: 1) a mystical brotherhood; 2) a tunnel entrance to a secret city inside Mount Shasta; 3) Lemuria; 4) the concept of "I AM"; 5) "channeling" of ethreal spirits; 6)a panther surprise" (1993; 143). The author claims to have written most of the novel within sight of Mount Shasta, and autobiographical telling of the story from Phylos the Thibetan's point of view is an interesting twist. We have included a few pages of text from the novel, including the reference to the mystic brotherhood that lives amid "the walls, polished as by jewelers, though excavated by giants; floors carpeted with long, fleecy gray fabric that looked like fur, but was a mineral product; ledges intersected by the builders, and in their wonderful polish exhibiting veinings of gold, of silver, of green copper ores, and maculations of precious stones." (Oliver 1905; 248).

[youtube=425,350]v/OvvpcKHn3DQ&hl=en&fs=1&"[/youtube]

In 1908, Adelia H. Taffinder wrote an article, "A Fragment of the Ancient Continent of Lemuria," for the Atlantic Monthly. In her article she links the concept of Lemuria to California, and Meisse proposses that the article, "with its Theosophical teachings and extension of the Lemurian Myth to California, may have been part of the research material involved in the creation of the Mount Shasta Lemurian Myth as presented by Selvius in 1925 and Creve in 1931" (1993; 147).

Selvius' 1925 two-page article, "Decendants of Lemuria" is, according to Meisse, "the singlemost inportant document in the establishment of the modern Mt. Shasta-Lemurian myth," so we have included Selvius' full-text article. Selvius claims that Professor Edgar Lucian Larkin viewed the Lemurian site on Mount Shasta using his telescope: "Even no less a careful investigator and scientist than Prof. Edgar Lucin Larkin, for many years director of Mount Lowe Observatory, said in newspaper and magazine articles that he had seen, on many occasions, the great temple of this mystic village, while gazing through a long-distance telescope."

Although Selvius' article is the most historically interesting, Wishar Spenle Cerve's 1931 Lemuria: The Lost Continent of the Pacific is, according to Meisse, "responsible for the legend's widespread popularity" (1993; 146). Perhaps most intriging is Meisse's speculation that "it appears from the similarity of material that "Selvius" and "Cerve" were one and the same person" (1993; 145). Further muddying the waters is Edward Stul's worth claim that "Wishar Spenly Cerve" is really a letter-for-letter pseudonym for "Harve Spencer Lewis," first Imperator of the Rosicrucian Order of North and South America. Still, it is Cerve's book, published by the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, that has provided the popular description of the Lemurians as "tall, graceful, and agile," and as visitors that "would come to one of the smaller towns and trade nuggets and gold dust for some modern commodities" (250).

The idea of a lost continent (and the subsequent existence of Lemurians on Mount Shasta), quickly became widely known, though perhaps not so widely believed. In 1939, Mount Shasta botanist William Cooke was in a Cincinati library when he was asked if he "knew anything about the LeMurians." A few months later, in a Mount Shasta Herald article called "Lights on Mt. Shasta: Evidences Discounted," Cooke questions the legend that Larkin could have used a telescope to see any structures on Mount Shasta. About a year later, in another Herald article, titled "Wm. Bridge Cooke Discusses 'Lost Continent' Book," Cooke questioned the possibility of a Lemuria or Mu (1941).

Today the belief that Lemurians inhabit the mountain is still very popular, and anyone visiting the local bookstores will likely be suprised by the plethora of texts on the subject.