Gypsy Heart

Gold Member

In Stevens Passage between Admiralty and Douglas Islands in the southern reaches of the state's Pacific coast the steamer Islander went down on August 15, 1901, with a reported $3,000,000 in gold and $400,000 in currency aboard. Forty people lost their lives.

In 1898 the Islander, once the presumed unsinkable steel hulled flagship of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, struck a submerged rock or iceberg while steaming at 15 knots and went under in less than 20 minutes. Numerous attempts to salvage the wreck were made, but it was not until 1934 that the remains of the Islander were raised from 300 feet. Both the Islander and the Griffson now rest ashore.

The steamer ISLANDER and schooner barge GRIFFSON, whose histories are intertwined, are located in state tidelands south of Juneau. The ISLANDER sank in deep water after hitting an iceberg or uncharted rock in August 1901. Most of the 170 persons on board were lost. With reports of gold on board, talk of salvage began almost immediately, but the depth of the wreck exceeded the limits of contemporary diving equipment. It wasn’t until 1921 that the wreck was discovered in 300 feet of water. It was viewed from a diving bell in 1929, and in 1934 a monumental salvage attempt was undertaken by use of the GRIFFSON and another barge. By cradling the ISLANDER on cables run between the two barges and using extreme tide cycles for lifting, the vessel was moved to the beach. Not enough gold was found to pay for the massive salvage effort, and it is speculated that most of the gold was in the bow, which broke off during salvage. The wooden hull of the GRIFFSON was abandoned on the beach, where it remains today, along with remnants of the steel-hulled ISLANDER. The wrecks were documented by project scientists during a low tide cycle.

On Monday September 9, 1901, King's Council E.V. Bodwell acknowledged receipt of his instructions to appear at the inquiry on behalf of the government. He immediately won an adjournment to allow time to produce new witnesses from among the Islander's passengers. He also secured the right to cross-examine the conduct of the crew and to take other measures to ensure that the inquiry was not seen to be helping the company to "whitewash its officers."

The new witnesses painted a very different picture than what had so far emerged, testifying that the sinking was accompanied by confusion and chaos. Passengers in their cabins were not informed there had been an accident; the captain was alleged to have been inebriated; and half-empty lifeboats containing crew members left the ship, leaving passengers stranded on deck. Only after the inquest had finished, when the North West Mounted Police inquired into compensation for lost goods, was it discovered that not all of the crew members were licensed for their profession.

The final, three-page finding of the inquiry was, among other items, critical of the captain for not ensuring a proper quota of people per boat and for not realizing the imminent danger that the ship was in. However, a short handwritten paragraph was inserted into the document, stating that the loss of the Islander was not due "to the intemperance of the Master [Captain] or Officers."

Reports of lucrative amounts of gold on board the sunken ship led to many early salvage efforts and several lawsuits. The main portion of the hull was discovered in 1934, but the bow section, where the gold was located, eluded the latter-day 'gold rushers' until 1996.

References

Clipping. Vancouver Daily World. August 19, 1901. Library and Archives Canada. RG 18. Volume 217. File 714-737.

Library and Archives Canada. RG 18. Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Series A-1. Volume 218. File 815-853.\

Library and Archives Canada. RG 12. Transport. Volume 1245. File 9704-199.

Examination of photographs taken at the time, revealed an unexplained mystery: the whole bow section of the ship - from the stem bar to the passenger accommodation forward bulkhead - was missing! According to statements made by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Constables who were onboard to guard the shipment, the gold bullion was stowed in a locker on the port side of the forward well deck, just abaft the break of the focsle. An area located within the 'missing' hull section, which remained missing until August 1996, when we located what remained of the steelwork, using sidescan sonar and a Remotely Operated Vehicle.

http://www.ssislander.co.uk/

On August 14, 1901 the Islander departed Skagway, Alaska bound for Victoria, British Columbia, filled to capacity with passengers and a cargo of gold bullion valued at over $6,000,000 in 1901 dollars. Sometime after 2:00 am in the early morning of August 15, while transiting the narrow Lynn Canal south of Juneau, she struck what was reported to be an iceberg that stove a large hole in her forward port quarter. Attempts to steer the foundering vessel ashore on nearby Douglas Island were in vain; within five minutes, the tremendous weight of the water filling the ship's forward compartments had forced her bow underwater and her stern, rudder and propellers completely out of the water.

After drifting for about 15 minutes in a strong southerly outbound tide, the Islander began her final plunge to the bottom.

Survivors clinging to the few seaworthy lifeboats reported that a 'whoosh' of escaping air and steam from the boilers blew the wooden upper works from the sinking ship, which rained down upon the horrified passengers in a hail of splinters and debris. The witnesses further reported that the Islander broke amidships before the once-proud steamer slipped beneath the seas to her final resting place in 175 feet of frigid water.

In addition to the financial blow, the Islander disaster claimed numerous prominent victims, among them Mrs. James H. Ross and her daughter, the wife and child of the Commissioner, the highest government official in the Yukon Territory; Charles Keating, a multimillionaire and Director of the Commerce Bank of Canada, with two of his sons; and Peter Warren Bell, a retired senior officer of the Hudson Bay Company, who was in the Yukon on personal business for a confidant of England's King Edward VII.

No sooner had the Islander sunk than efforts to locate the shipwreck began. Within days, her sister ship, the Haling, was sounding the uncharted bottom in order to determine the depth of the sunken liner. The first attempt to find the Islander was a failure, but within one year, Henry Finch, a seasoned deep sea diver with 40 years underwater experience, was on the Lynn Canal dragging the bottom for the sunken hull. He eventually located the hull in 1902 but was not able to progress further at that time with an actual salvage effort. In 1904, equipped with a newly designed barge and diving bell, the tenacious Finch succeeded in relocating the shipwreck in 175 feet of frigid water. Peering into the black abyss from a primitive diving bell, Finch reported a "gaping hole" in the Islander's bow. Unfortunately, the salvors did not have the ability to grapple the wreck with sufficient strength to gain access to the reputed location of the gold bullion in the Purser's Office amidships. As a consequence, only a piece of the Islander's deck rail and grating were recovered that year. In spite of his frustration, Finch could never forget the tantalizing lure of the vast shipwrecked treasure. Over the next 25 years, a seemingly never-ending procession of bold professional salvors pitted themselves against the formidable challenge of the Islander. Each of these well financed operations succeeded in reaching the sunken liner, but none was able to penetrate her hold or recover any of the gold cargo. The adverse conditions of poor weather topside, nearly nonexistent visibility, powerful currents and extremely cold temperature notwithstanding, salvage from such depths was virtually unheard of in those days. Nevertheless, at least a dozen separate salvage ventures were attempted during 21 different seasons. In 1929 the Willey group teamed with Frank Curtis, a professional house mover with extensive experience in transporting large structures. Their plan was to string 20 sturdy steel cables beneath the sunken liner that were connected to surface vessels. The cables were cinched up with each low tide, enabling the shipwreck to be inched toward shore with each high tide. This grueling operation took two full salvage seasons until, on July 20, 1934, the Islander once again broke the surface near Green's Cove, Admiralty Island, Alaska.

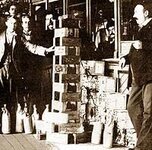

In the cruelest of disappointments, however, the Islander would yield the paltry sum of $75,000.00 worth of gold nuggets and dust. When cleared of muck, the long anticipated Purser's Office proved to be a truly bitter washout: none of the reputed ironbound strong boxes of bullion ingots were found; its safe contained a handful of U.S. $10.00 and $20.00 gold pieces and a stack of rancid U.S. and Canadian paper currency. After 33 years of virtual nonstop, back-and-spirit breaking toil, the Islander, having been laboriously wrenched from her frozen tomb, had the last laugh: her priceless tons of gold bullion lay undisturbed on the bottom of Lynn Canal, still ensconced in the Mail and Storage Room, in the unrecovered bow of the shipwreck.

Salvage Efforts 1996

OceanMar Inc of Seattle, having first obtained a 'Salvage Agreement' from the Salvage Association of London, raised sufficient capital in the USA and UK, to charter a suitable vessel, the MV Jolly Roger out of Santa Barbara, and mount a properly equipped expedition. Sailing from Tacoma Seattle, where the ship had been extensively fitted out, Ted Jaynes, founder and President of OceanMar, Nick Messinger submariner and former deep diving operations manager, Ian Blamire, another Englishman and Managing Director of Sea Eye Marine of Gosport, had high expectations of salvaging Islander's bow section and recovering the elusive gold bullion and ore in concentrate. The three men, all former employees of InterSub - International Submarine Services of Marseilles, France, were highly experienced professionals, and with an extensive sidescan sonar suite, high-tech Sea Eye Marine 'Surveyor' ROV (remotely operated vehicle) and surface and subsea acoustic navigation and tracking systems, they were the most well equipped expedition thus far. On arrival Juneau, alongside the jetty and taking on fresh water, the Jolly Roger was boarded by a US Deputy Marshall, who served a Temporary Restraining Order, obtained by another salvage company, Yukon Recovery of Seattle. Yukon claimed rights to the wreck on the basis that they had removed a light fitting and a bottle, under the law of 'finder's keepers' and the Abandoned Shipwreck Act. OceanMar, having spent over seven years extensively researching the Islander disaster, claimed that the wreck had never been abandoned and that their Salvage Agreement with the original insurers, therefore took precedence. OceanMar were also able to demonstrate that they had located the bow long before Yukon appeared on the scene. A visit to Anchorage and a meeting with the judge, fortunately an expert in maritime affairs, resulted in permission being granted for OceanMar to survey and video the wreck site, but on the strict understanding that nothing would be removed. Somewhat demoralized at the turn of events, Jolly Roger and her crew set sail, and spent the next five weeks on site, recording every aspect of the bow section and side-scanning the debris field, between the original point of impact and the final resting place. They were on site in the Gastineau Canal, on the 95th anniversary of the sinking, 15th August 1996. There then followed four long years of expensive legal battle with Yukon Recovery, resulting in the US Court of Appeal For the 9th District, finding in favour of OceanMar on 7th March 2000, Case Number 98-36015

In 1898 the Islander, once the presumed unsinkable steel hulled flagship of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, struck a submerged rock or iceberg while steaming at 15 knots and went under in less than 20 minutes. Numerous attempts to salvage the wreck were made, but it was not until 1934 that the remains of the Islander were raised from 300 feet. Both the Islander and the Griffson now rest ashore.

The steamer ISLANDER and schooner barge GRIFFSON, whose histories are intertwined, are located in state tidelands south of Juneau. The ISLANDER sank in deep water after hitting an iceberg or uncharted rock in August 1901. Most of the 170 persons on board were lost. With reports of gold on board, talk of salvage began almost immediately, but the depth of the wreck exceeded the limits of contemporary diving equipment. It wasn’t until 1921 that the wreck was discovered in 300 feet of water. It was viewed from a diving bell in 1929, and in 1934 a monumental salvage attempt was undertaken by use of the GRIFFSON and another barge. By cradling the ISLANDER on cables run between the two barges and using extreme tide cycles for lifting, the vessel was moved to the beach. Not enough gold was found to pay for the massive salvage effort, and it is speculated that most of the gold was in the bow, which broke off during salvage. The wooden hull of the GRIFFSON was abandoned on the beach, where it remains today, along with remnants of the steel-hulled ISLANDER. The wrecks were documented by project scientists during a low tide cycle.

On Monday September 9, 1901, King's Council E.V. Bodwell acknowledged receipt of his instructions to appear at the inquiry on behalf of the government. He immediately won an adjournment to allow time to produce new witnesses from among the Islander's passengers. He also secured the right to cross-examine the conduct of the crew and to take other measures to ensure that the inquiry was not seen to be helping the company to "whitewash its officers."

The new witnesses painted a very different picture than what had so far emerged, testifying that the sinking was accompanied by confusion and chaos. Passengers in their cabins were not informed there had been an accident; the captain was alleged to have been inebriated; and half-empty lifeboats containing crew members left the ship, leaving passengers stranded on deck. Only after the inquest had finished, when the North West Mounted Police inquired into compensation for lost goods, was it discovered that not all of the crew members were licensed for their profession.

The final, three-page finding of the inquiry was, among other items, critical of the captain for not ensuring a proper quota of people per boat and for not realizing the imminent danger that the ship was in. However, a short handwritten paragraph was inserted into the document, stating that the loss of the Islander was not due "to the intemperance of the Master [Captain] or Officers."

Reports of lucrative amounts of gold on board the sunken ship led to many early salvage efforts and several lawsuits. The main portion of the hull was discovered in 1934, but the bow section, where the gold was located, eluded the latter-day 'gold rushers' until 1996.

References

Clipping. Vancouver Daily World. August 19, 1901. Library and Archives Canada. RG 18. Volume 217. File 714-737.

Library and Archives Canada. RG 18. Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Series A-1. Volume 218. File 815-853.\

Library and Archives Canada. RG 12. Transport. Volume 1245. File 9704-199.

Examination of photographs taken at the time, revealed an unexplained mystery: the whole bow section of the ship - from the stem bar to the passenger accommodation forward bulkhead - was missing! According to statements made by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Constables who were onboard to guard the shipment, the gold bullion was stowed in a locker on the port side of the forward well deck, just abaft the break of the focsle. An area located within the 'missing' hull section, which remained missing until August 1996, when we located what remained of the steelwork, using sidescan sonar and a Remotely Operated Vehicle.

http://www.ssislander.co.uk/

On August 14, 1901 the Islander departed Skagway, Alaska bound for Victoria, British Columbia, filled to capacity with passengers and a cargo of gold bullion valued at over $6,000,000 in 1901 dollars. Sometime after 2:00 am in the early morning of August 15, while transiting the narrow Lynn Canal south of Juneau, she struck what was reported to be an iceberg that stove a large hole in her forward port quarter. Attempts to steer the foundering vessel ashore on nearby Douglas Island were in vain; within five minutes, the tremendous weight of the water filling the ship's forward compartments had forced her bow underwater and her stern, rudder and propellers completely out of the water.

After drifting for about 15 minutes in a strong southerly outbound tide, the Islander began her final plunge to the bottom.

Survivors clinging to the few seaworthy lifeboats reported that a 'whoosh' of escaping air and steam from the boilers blew the wooden upper works from the sinking ship, which rained down upon the horrified passengers in a hail of splinters and debris. The witnesses further reported that the Islander broke amidships before the once-proud steamer slipped beneath the seas to her final resting place in 175 feet of frigid water.

In addition to the financial blow, the Islander disaster claimed numerous prominent victims, among them Mrs. James H. Ross and her daughter, the wife and child of the Commissioner, the highest government official in the Yukon Territory; Charles Keating, a multimillionaire and Director of the Commerce Bank of Canada, with two of his sons; and Peter Warren Bell, a retired senior officer of the Hudson Bay Company, who was in the Yukon on personal business for a confidant of England's King Edward VII.

No sooner had the Islander sunk than efforts to locate the shipwreck began. Within days, her sister ship, the Haling, was sounding the uncharted bottom in order to determine the depth of the sunken liner. The first attempt to find the Islander was a failure, but within one year, Henry Finch, a seasoned deep sea diver with 40 years underwater experience, was on the Lynn Canal dragging the bottom for the sunken hull. He eventually located the hull in 1902 but was not able to progress further at that time with an actual salvage effort. In 1904, equipped with a newly designed barge and diving bell, the tenacious Finch succeeded in relocating the shipwreck in 175 feet of frigid water. Peering into the black abyss from a primitive diving bell, Finch reported a "gaping hole" in the Islander's bow. Unfortunately, the salvors did not have the ability to grapple the wreck with sufficient strength to gain access to the reputed location of the gold bullion in the Purser's Office amidships. As a consequence, only a piece of the Islander's deck rail and grating were recovered that year. In spite of his frustration, Finch could never forget the tantalizing lure of the vast shipwrecked treasure. Over the next 25 years, a seemingly never-ending procession of bold professional salvors pitted themselves against the formidable challenge of the Islander. Each of these well financed operations succeeded in reaching the sunken liner, but none was able to penetrate her hold or recover any of the gold cargo. The adverse conditions of poor weather topside, nearly nonexistent visibility, powerful currents and extremely cold temperature notwithstanding, salvage from such depths was virtually unheard of in those days. Nevertheless, at least a dozen separate salvage ventures were attempted during 21 different seasons. In 1929 the Willey group teamed with Frank Curtis, a professional house mover with extensive experience in transporting large structures. Their plan was to string 20 sturdy steel cables beneath the sunken liner that were connected to surface vessels. The cables were cinched up with each low tide, enabling the shipwreck to be inched toward shore with each high tide. This grueling operation took two full salvage seasons until, on July 20, 1934, the Islander once again broke the surface near Green's Cove, Admiralty Island, Alaska.

In the cruelest of disappointments, however, the Islander would yield the paltry sum of $75,000.00 worth of gold nuggets and dust. When cleared of muck, the long anticipated Purser's Office proved to be a truly bitter washout: none of the reputed ironbound strong boxes of bullion ingots were found; its safe contained a handful of U.S. $10.00 and $20.00 gold pieces and a stack of rancid U.S. and Canadian paper currency. After 33 years of virtual nonstop, back-and-spirit breaking toil, the Islander, having been laboriously wrenched from her frozen tomb, had the last laugh: her priceless tons of gold bullion lay undisturbed on the bottom of Lynn Canal, still ensconced in the Mail and Storage Room, in the unrecovered bow of the shipwreck.

Salvage Efforts 1996

OceanMar Inc of Seattle, having first obtained a 'Salvage Agreement' from the Salvage Association of London, raised sufficient capital in the USA and UK, to charter a suitable vessel, the MV Jolly Roger out of Santa Barbara, and mount a properly equipped expedition. Sailing from Tacoma Seattle, where the ship had been extensively fitted out, Ted Jaynes, founder and President of OceanMar, Nick Messinger submariner and former deep diving operations manager, Ian Blamire, another Englishman and Managing Director of Sea Eye Marine of Gosport, had high expectations of salvaging Islander's bow section and recovering the elusive gold bullion and ore in concentrate. The three men, all former employees of InterSub - International Submarine Services of Marseilles, France, were highly experienced professionals, and with an extensive sidescan sonar suite, high-tech Sea Eye Marine 'Surveyor' ROV (remotely operated vehicle) and surface and subsea acoustic navigation and tracking systems, they were the most well equipped expedition thus far. On arrival Juneau, alongside the jetty and taking on fresh water, the Jolly Roger was boarded by a US Deputy Marshall, who served a Temporary Restraining Order, obtained by another salvage company, Yukon Recovery of Seattle. Yukon claimed rights to the wreck on the basis that they had removed a light fitting and a bottle, under the law of 'finder's keepers' and the Abandoned Shipwreck Act. OceanMar, having spent over seven years extensively researching the Islander disaster, claimed that the wreck had never been abandoned and that their Salvage Agreement with the original insurers, therefore took precedence. OceanMar were also able to demonstrate that they had located the bow long before Yukon appeared on the scene. A visit to Anchorage and a meeting with the judge, fortunately an expert in maritime affairs, resulted in permission being granted for OceanMar to survey and video the wreck site, but on the strict understanding that nothing would be removed. Somewhat demoralized at the turn of events, Jolly Roger and her crew set sail, and spent the next five weeks on site, recording every aspect of the bow section and side-scanning the debris field, between the original point of impact and the final resting place. They were on site in the Gastineau Canal, on the 95th anniversary of the sinking, 15th August 1996. There then followed four long years of expensive legal battle with Yukon Recovery, resulting in the US Court of Appeal For the 9th District, finding in favour of OceanMar on 7th March 2000, Case Number 98-36015

Attachments

-

Douglas Island Alaska.gif92.1 KB · Views: 2,726

Douglas Island Alaska.gif92.1 KB · Views: 2,726 -

islander.jpg10.4 KB · Views: 2,759

islander.jpg10.4 KB · Views: 2,759 -

Islander 1897.jpg2.9 KB · Views: 2,720

Islander 1897.jpg2.9 KB · Views: 2,720 -

Stevens Passage.jpg115.9 KB · Views: 1,476

Stevens Passage.jpg115.9 KB · Views: 1,476 -

side scan bow and debris.jpg27.4 KB · Views: 1,447

side scan bow and debris.jpg27.4 KB · Views: 1,447 -

Klondike Gold Bars.jpg16.4 KB · Views: 2,819

Klondike Gold Bars.jpg16.4 KB · Views: 2,819 -

Bow wreck site 1996.jpg129.6 KB · Views: 1,520

Bow wreck site 1996.jpg129.6 KB · Views: 1,520