- Jan 27, 2009

- 18,792

- 11,909

- 🥇 Banner finds

- 1

- Detector(s) used

- Tesoro Conquistador freq shift

Fisher F75

Garrett AT-Pro

Garet carrot

Neodymium magnets

5' Probe

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

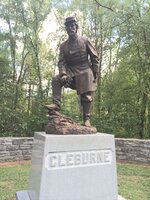

Sun was setting and I had a crappy camera but tried to lighten them a little. This guy was the man. I have hunted many of his battles around my area.And am hunting one more now. He always held his positions or advanced when other fell. Enjoy the pics and the short story.

Click to enlarge and see the details.

The Death of Major-General Patrick Cleburne

In the early afternoon of 30th November 1864 Brigadier-General Daniel C. Govan stood with his Division Commander Major-General Patrick Cleburne on Winstead Hill, Tennessee. As they prepared their troops for an attack on the fortified Federal positions around the town of Franklin, Govan looked out across the exposed plain over which the Army of Tennessee must advance. Their prospects of success looked bleak. Govan was the last to speak to Cleburne prior to the assault, remarking to him: ‘Well General, there will not be many of us that will get back to Arkansas.’ Cleburne, who Govan felt appeared despondent, replied: ‘Well Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men’ (1). While Govan did survive to see Arkansas once again, by day’s end, in the words of his former Adjutant Captain Irving A. Buck, ‘the inspiring voice of Cleburne was already hushed in death’ (2).

The Confederate assault against the Union centre at the Battle of Gettysburg, ‘Pickett’s Charge’, has become the iconic symbol of a desperate but futile Southern effort to break their enemy’s line. However, the Confederate assault by the Army of Tennessee at Franklin was both larger and bloodier. The heaviest of the fighting took place in a period of two hours, with the general engagement lasting some five hours. When the battle ended, at least 8,500 Union and Confederate soldiers were casualties (3). The unimaginable carnage effectively destroyed the Army of Tennessee; apart from the colossal casualties experienced amongst the rank and file, no less than six Confederate Generals were killed or mortally wounded. Amongst them was Corkman Patrick Cleburne, the most highly regarded Division commander in the army and the highest ranking Irishman in the Confederacy.

But what of Cleburne’s final moments? Captain Buck, who was absent from Franklin due to wounds received at Jonesboro in September 1864, was eager to ascertain the particulars of Cleburne’s death in so far as was possible. He corresponded with members of the Army of Tennessee present at Franklin and also collected as much published information as he could relating to his old commander’s demise. The results of his research were published as part of his 1908 book Cleburne and his Command. His correspondence with Brigadier-General Govan added further detail with regard to Cleburne’s movements:

‘After receiving his final orders we were directed to advance, which was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon. We had to advance across an old open common, subjected to the heavy fire of the Federal forces. We met the enemy in a short space of time and carried the first line commanded by General Wagner [this force had foolishly been holding a position well in advance of the main Union line]. When that line was broken, General Cleburne’s object seemed to be to run into the rear line with the fleeing Federal’s from Wagner’s division. About that time General Cleburne’s horse was killed. His courier brought him another, and as he was in the act of mounting, this horse was killed. He then disappeared in the smoke of battle, and that was the last time I ever saw him alive. I spoke to his aide-de-camp, Mangum, and told him I was sure the General would be killed, as I did not see how he could escape with his life under such terrific fire, and as he never again appeared in the lines, confirmed my opinion that he was dead’ (4).

General Govan had also corresponded with Captain Dinkins for an article in the New Orleans Picayunewhere he added further detail to Cleburne’s experience at Franklin. When Cleburne’s first horse was killed under him Govan was nearby, and he noted that the mortally wounded animal’s momentum carried the horse and rider nearly to the ditch on the outside of the Federal entrenchments. The second horse was struck by a cannonball from the direction of the Cotton Ginwhile Cleburne was in the act of mounting. At this point the Irishman moved forward towards the enemy works on foot, waving his cap and encouraging his men to advance. According to Govan Cleburne’s body was eventually found some twenty yards from where he had last seen him. Another officer to comment on Cleburne’s whereabouts was C.W. Frazer who had served in Cleburne’s Division up to the Battle of Murfreesboro, and who wrote a history of the 5th Confederate Regiment after the war. This unit was principally made up of Irishmen from Memphis, and Frazer maintained that the General sought out the Regiment at Franklin, ‘charged in with it, and died with it’ (5).

The following morning the death of Patrick Cleburne was confirmed. Mr. John McQuade of Vicksburg, Mississippi takes up the story: ‘I and two others were the first to discover his dead body at early dawn the next morning. He was about 40 or 50 yards from the works. He lay flat upon his back as if asleep, his military cap partly over his eyes. He had on a new gray uniform, the coat of the sack or blouse pattern. It was unbuttoned and open; the lower part of his vest was unbuttoned and open. He wore a white linen shirt, which was stained with blood on the front part of the left side, or just left of the abdomen. This was the only sign of a wound I saw on him, and I believe it is the only one he had received. I have always been inclined to think that feeling the end was near, he had thus laid himself down to die, or that his body had been carried there during the night. He was in his sock feet, his boots having been stolen. His watch, sword belt and other valuables were all gone, his body having been robbed during the night’ (6). McQuade approached an ambulance picking up wounded men and dead officers under the charge of Reverend Thomas Markham. Cleburne’s body was placed beside that of Brigadier-General John Adams and taken to the McGavock residence at the nearby Carnton Plantation. There Generals Cleburne, Adams, Strahl and Granbury would lie side by side on the porch prior to their burial. Earlier in the year Cleburne had become engaged to Susan Tarleton of Mobile, Alabama. On 5th December 1864 Susan was walking in the garden in Mobile where she and Patrick had become engaged. A boy on the street selling papers shouted out the days headline ‘Reports from Tennessee! Cleburne and other Generals killed’. She promptly fainted (7).

Major-General Patrick Ronanyne Cleburne was initially interred at Rose Hill near Franklin. His body was moved to St. John’s Church, Ashwood, Tennessee thereafter; Cleburne had passed the cemetery a few days earlier during the advance into Tennessee and had remarked that it was ‘almost worth dying for, to be buried in such a beautiful spot’ (8). In 1870 he would be moved once again, this time returning to his adopted State in Arkansas, where he remains in Maple Hill Cemetery, Helena.

The impact of the death of Major-General Patrick Cleburne was keenly felt. No less a personage than Robert E. Lee described him as ‘A meteor shining from a clouded sky’. The memory of the Irishman remains strong in the United States today. He has had locations named for him in Alabama, Arkansas and Texas, a Confederate Cemetery named after him in Georgia, been the subject of a number of books, has had a society set up in his honour, a statue erected at the scene of perhaps his greatest victory in Ringgold, Georgia, and a park created at the scene of his death in Franklin. In stark contrast, he remains virtually unheard of in his native country, a situation which it is hoped can be altered in the not too distant future.

(

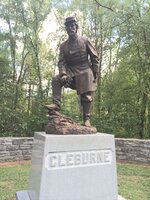

Click to enlarge and see the details.

The Death of Major-General Patrick Cleburne

In the early afternoon of 30th November 1864 Brigadier-General Daniel C. Govan stood with his Division Commander Major-General Patrick Cleburne on Winstead Hill, Tennessee. As they prepared their troops for an attack on the fortified Federal positions around the town of Franklin, Govan looked out across the exposed plain over which the Army of Tennessee must advance. Their prospects of success looked bleak. Govan was the last to speak to Cleburne prior to the assault, remarking to him: ‘Well General, there will not be many of us that will get back to Arkansas.’ Cleburne, who Govan felt appeared despondent, replied: ‘Well Govan, if we are to die, let us die like men’ (1). While Govan did survive to see Arkansas once again, by day’s end, in the words of his former Adjutant Captain Irving A. Buck, ‘the inspiring voice of Cleburne was already hushed in death’ (2).

The Confederate assault against the Union centre at the Battle of Gettysburg, ‘Pickett’s Charge’, has become the iconic symbol of a desperate but futile Southern effort to break their enemy’s line. However, the Confederate assault by the Army of Tennessee at Franklin was both larger and bloodier. The heaviest of the fighting took place in a period of two hours, with the general engagement lasting some five hours. When the battle ended, at least 8,500 Union and Confederate soldiers were casualties (3). The unimaginable carnage effectively destroyed the Army of Tennessee; apart from the colossal casualties experienced amongst the rank and file, no less than six Confederate Generals were killed or mortally wounded. Amongst them was Corkman Patrick Cleburne, the most highly regarded Division commander in the army and the highest ranking Irishman in the Confederacy.

But what of Cleburne’s final moments? Captain Buck, who was absent from Franklin due to wounds received at Jonesboro in September 1864, was eager to ascertain the particulars of Cleburne’s death in so far as was possible. He corresponded with members of the Army of Tennessee present at Franklin and also collected as much published information as he could relating to his old commander’s demise. The results of his research were published as part of his 1908 book Cleburne and his Command. His correspondence with Brigadier-General Govan added further detail with regard to Cleburne’s movements:

‘After receiving his final orders we were directed to advance, which was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon. We had to advance across an old open common, subjected to the heavy fire of the Federal forces. We met the enemy in a short space of time and carried the first line commanded by General Wagner [this force had foolishly been holding a position well in advance of the main Union line]. When that line was broken, General Cleburne’s object seemed to be to run into the rear line with the fleeing Federal’s from Wagner’s division. About that time General Cleburne’s horse was killed. His courier brought him another, and as he was in the act of mounting, this horse was killed. He then disappeared in the smoke of battle, and that was the last time I ever saw him alive. I spoke to his aide-de-camp, Mangum, and told him I was sure the General would be killed, as I did not see how he could escape with his life under such terrific fire, and as he never again appeared in the lines, confirmed my opinion that he was dead’ (4).

General Govan had also corresponded with Captain Dinkins for an article in the New Orleans Picayunewhere he added further detail to Cleburne’s experience at Franklin. When Cleburne’s first horse was killed under him Govan was nearby, and he noted that the mortally wounded animal’s momentum carried the horse and rider nearly to the ditch on the outside of the Federal entrenchments. The second horse was struck by a cannonball from the direction of the Cotton Ginwhile Cleburne was in the act of mounting. At this point the Irishman moved forward towards the enemy works on foot, waving his cap and encouraging his men to advance. According to Govan Cleburne’s body was eventually found some twenty yards from where he had last seen him. Another officer to comment on Cleburne’s whereabouts was C.W. Frazer who had served in Cleburne’s Division up to the Battle of Murfreesboro, and who wrote a history of the 5th Confederate Regiment after the war. This unit was principally made up of Irishmen from Memphis, and Frazer maintained that the General sought out the Regiment at Franklin, ‘charged in with it, and died with it’ (5).

The following morning the death of Patrick Cleburne was confirmed. Mr. John McQuade of Vicksburg, Mississippi takes up the story: ‘I and two others were the first to discover his dead body at early dawn the next morning. He was about 40 or 50 yards from the works. He lay flat upon his back as if asleep, his military cap partly over his eyes. He had on a new gray uniform, the coat of the sack or blouse pattern. It was unbuttoned and open; the lower part of his vest was unbuttoned and open. He wore a white linen shirt, which was stained with blood on the front part of the left side, or just left of the abdomen. This was the only sign of a wound I saw on him, and I believe it is the only one he had received. I have always been inclined to think that feeling the end was near, he had thus laid himself down to die, or that his body had been carried there during the night. He was in his sock feet, his boots having been stolen. His watch, sword belt and other valuables were all gone, his body having been robbed during the night’ (6). McQuade approached an ambulance picking up wounded men and dead officers under the charge of Reverend Thomas Markham. Cleburne’s body was placed beside that of Brigadier-General John Adams and taken to the McGavock residence at the nearby Carnton Plantation. There Generals Cleburne, Adams, Strahl and Granbury would lie side by side on the porch prior to their burial. Earlier in the year Cleburne had become engaged to Susan Tarleton of Mobile, Alabama. On 5th December 1864 Susan was walking in the garden in Mobile where she and Patrick had become engaged. A boy on the street selling papers shouted out the days headline ‘Reports from Tennessee! Cleburne and other Generals killed’. She promptly fainted (7).

Major-General Patrick Ronanyne Cleburne was initially interred at Rose Hill near Franklin. His body was moved to St. John’s Church, Ashwood, Tennessee thereafter; Cleburne had passed the cemetery a few days earlier during the advance into Tennessee and had remarked that it was ‘almost worth dying for, to be buried in such a beautiful spot’ (8). In 1870 he would be moved once again, this time returning to his adopted State in Arkansas, where he remains in Maple Hill Cemetery, Helena.

The impact of the death of Major-General Patrick Cleburne was keenly felt. No less a personage than Robert E. Lee described him as ‘A meteor shining from a clouded sky’. The memory of the Irishman remains strong in the United States today. He has had locations named for him in Alabama, Arkansas and Texas, a Confederate Cemetery named after him in Georgia, been the subject of a number of books, has had a society set up in his honour, a statue erected at the scene of perhaps his greatest victory in Ringgold, Georgia, and a park created at the scene of his death in Franklin. In stark contrast, he remains virtually unheard of in his native country, a situation which it is hoped can be altered in the not too distant future.

(

Upvote

0