Gypsy Heart

Gold Member

Fort Marcy became the first United States Army post established in the Southwest. At the outbreak of the Mexican War, Gen. Stephen W. Kearny and his troops marched over the Santa Fe Trail, seizing Santa Fe on Aug. 18, 1846.

The very next day, he sent two of his engineers, lieutenants William Emory and Jeremy Gilmer, on a scout to find a good defensive site for a fort. This was considered necessary, since an uprising by the conquered population was still feared.

Lt. Emory discovered just the place-what he described as "the only point which commands the entire town." It was on the summit of a flat-topped hill, only 650 yards northeast of the Plaza. A half-dozen cannons positioned there could rule Santa Fe.

Soldiers and hired workmen threw up thick adobe walls, 9 feet high and surrounded by a deep ditch. A log structure inside the compound provided a magazine for storing gunpowder. Gen. Kearny named the new installation after William L. Marcy, the secretary of war at that time, and his boss.

Fort Marcy was originally intended for a garrison of 280 men, but no quarters were provided for them inside the fort. Instead, the men were lodged and the horses were corralled in and around the old Spanish military barracks next to the Governors' Palace.

It was thought that in case of trouble the men should scurry up to the fort and defend the walls. As late as 1853, military inspector Col. Joseph Mansfield described Marcy as "the only real fort in the territory." Fort Union, located on the Santa Fe Trail east of Las Vegas, had been founded but was still a flimsy collection of huts.

Downriver, the Post of El Paso, founded on Sept. 28, 1849, briefly had six companies of the Third Infantry, but its soldiers were soon dispersed to other stations in southern New Mexico. Its substantial successor, Fort Bliss, did not come into being until 1854.

Since Marcy's troops were all quartered in town and there existed no threat of attack, the walls of the fort on the hill were allowed to deteriorate. Only the magazine continued in use, since it remained the safest place to keep powder, away from the townsfolk.

Santa Fe resident Marian Russell remembered that after Fort Marcy fell to ruin, local people used it for a burial ground. "One dear old lady, a Mrs. Sutton," she recalled, had a 19-year-old son buried in the fort. He had been a drummer boy in the Civil War. Coming home, he had been bitten by a mad dog on the streets of Santa Fe and died of hydrophobia. Daily Mrs. Sutton climbed the steep hill to Fort Marcy to place flowers or some little offering on her son's grave."

During 1887, a small incident occurred that must have severely impacted what was left of the fort. On Sept. 30, the Silver City Enterprise reported that a local citizen, Mrs. Tassie Wilson, had gone to the territorial capital for a visit. While there, she and friends had unearthed a trove of Spanish coins buried under the walls of old Fort Marcy.

The value of the find, said the Enterprise, was more than $2,300. The oldest coins were dated 1726 and 1740, and these had been donated to the Historical Society of New Mexico. And the paper added: "After the discovery was made, large numbers of Santa Fe citizens turned out and dug the whole country up in the vicinity of the fort, but without finding anything new." That frenzied treasure hunt must have destroyed the last of the standing walls.

In 1891, the government sold the Fort Marcy property at auction. The site on the hill was acquired by the city of Santa Fe in 1961, landscaped and turned into a scenic overlook. It is not well advertised or marked, and many visitors today miss this special place.

The remains of Fort Marcy on the hill above Santa Fe consist of mounds of earth several feet high tracing the outline of the adobe fortification. There is now an apartment complex NW of the remaining mounds. Photo shows the earthen mounds of Fort Marcy, atop Fort Marcy Hill.

This Certified Site of the Santa Fe National Historic Trail is located in the Santa Fe Historic District. The earthen fort was large enough to accommodate 1,000 soldiers. It was never completed and was abandoned in 1868. Fort Marcy symbolizes the Americn conquest. Situated on a hill above town, it was built by the US Army under Gen. Stephen W. Kearny in 1846 to protect the American presence in Santa Fe. It was the 1st military post in what later became the Mexican cession.

Location Information

View the Google Map for this site (lat-long decimal degrees, NAD27) 35.68950-105.93029

Paul Weideman

February 19, 2004

One of the treasures in the files (paper, not digital) at the Santa Fe City Hall is an historic-buildings survey entry on the old Hilario Gallegos House at 334 Otero Street.

The survey writers presented a history of the known owners of the home but went further, placing it in the context of an area of importance successively to American Indians, Spanish colonists and the American, Civil-War-era Army of the West.

The hill on which the house was built was an attractive dwelling site because of the cultivable land of a spring-fed ciŽnega (marsh) that once stretched from just east of present-day Washington Avenue all the way to the Santa Fe River. Archaeologists believe Indians lived in the area from about 1000 to 1350 A.D. By the 1630s the hill and cienega were the property of Diego de Moraga. Indians regained control of the hill during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680-92 and used the elevation advantage to fire upon the Spanish in the villa below.

Five years after the reconquest de Moragas granddaughter, Antonia de Moraga, built a torre—n (tower), likely on the site of an Indian kiva structure, and lived in it while she farmed the land.

Another early structure in the area was a garita (guardhouse) built in 1806. (This, along with an adjacent mortuary chapel and cemetery, were tourist attractions until well into the 20th century.) The strategic importance of the hill was immediately realized by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officers upon the arrival of Gen. Stephen Watts Kearnys army in Santa Fe in August of 1846, the year a quarter century of Mexican rule in New Mexico ended.

On May 13, 1846, the United States Congress declared war with Mexico, and three months later Kearny and his Army of the West marched along the Santa Fe Trail into New Mexicos undefended northern frontier, writes Robert Torrez in an online history of New Mexico. ...

General Kearny entered Santa Fe on Aug. 18, 1846, and took possession of New Mexico without firing a shot. It was a bloodless conquest, accomplished through diplomacy and guile, much as Diego de Vargas had done during the reconquista of 1692.

Fort Marcy, the adobe stronghold Kearny built on the hill, was large enough to accommodate 1,000 soldiers. The war with Mexico ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 but the fort served the Army again during the Civil War at least until early March 1862 when Union troops at Fort Marcy evacuated the capital as Confederate forces from Texas approached Santa Fe. For two weeks before a Union victory at Apache Canyon settled the local conflict, a Confederate flag flew over Santa Fes ancient Palace of the Governors.

Old maps of the Fort Marcy facilities show the fort situated on the hill near the present-day Cross of the Martyrs (not to be confused with the original cross off Paseo de la Loma) as well as a number of structures in the downtown area: the district headquarters where the Museum of Fine Arts now sits; officers and company quarters between Grant and Lincoln; and stables, corrals, blacksmith, commissary store and a mule shed between Lincoln and Washington.

According to stories related long ago by Hispanics living in the area, the venerable house on Otero was one of the oldest in Santa Fe and was partly built by Indians. Hilario Gallegos, a young farm laborer, owned it in the 1860s. Thirty years later part of the structure, which included several units, was owned by the Conway family, one of whose children, John Conway, went on to serve as county superintendent and school superintendent. Among his accomplishments was the building of 40 schoolhouses in the rural districts of Santa Fe County.

Before the construction of the Campanilla Compound condominiums on the site the historic-buildings survey notes that the cost of the condo complex included the loss of the homes architectural integrity and historic context the Hilario Gallegos House was a sprawling adobe structure with two sets of U-shaped wings enclosing placitas.

Another of the Otero Street adobes with a dramatic piece of 19th-century history is at 300 Otero. Juan and Apollonia Holmes bought the house in 1888. Juan was a deputy sheriff who was involved in an intriguing murder case.

On March 4, 1890, the Santa Fe Daily New Mexican reported the disappearance of a citizen named Faustin Ortiz. Nine days later the paper said rumors were spreading, that the town was frazzled, and that a man who had supposedly last seen Ortiz began crying and behaving insanely on the Plaza.

By March 25 Ortiz was presumed dead and a high Mass was celebrated for him. Three days later his badly beaten and shot body was discovered in an arroyo. The investigation led that August to a grand jury indicting Holmes, sheriff Francisco Chavez and six other prominent lawmakers in the murder.

The residential development of the area east of Bishops Lodge Road began in 1887 with a plan for villa residences called Fort Marcy Heights. The plan fell through, resurfacing in 1912 as 114 lots north and east of the Fort Marcy ruins; platted streets included Prince, Emory, Gilmer and MacLean.

The Garita Addition, begun in 1910, involved 22 lots on Garita Place and Magdalena Road. By 1933 more homes were being built on new streets named Artist, Sunset and Monte Vista. The southern edge of the neighborhood was redefined with the 1972 creation of Paseo de Peralta.

Fort Marcy Park has long served as the site of the annual burning of Zozobra or Old Man Gloom. The tall figure, created and festively tortured and burned each year by the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe, was conceived by artist Will Shuster in 1926.

................................

additional info

http://www.nmgs.org/artcuar6.htm

The very next day, he sent two of his engineers, lieutenants William Emory and Jeremy Gilmer, on a scout to find a good defensive site for a fort. This was considered necessary, since an uprising by the conquered population was still feared.

Lt. Emory discovered just the place-what he described as "the only point which commands the entire town." It was on the summit of a flat-topped hill, only 650 yards northeast of the Plaza. A half-dozen cannons positioned there could rule Santa Fe.

Soldiers and hired workmen threw up thick adobe walls, 9 feet high and surrounded by a deep ditch. A log structure inside the compound provided a magazine for storing gunpowder. Gen. Kearny named the new installation after William L. Marcy, the secretary of war at that time, and his boss.

Fort Marcy was originally intended for a garrison of 280 men, but no quarters were provided for them inside the fort. Instead, the men were lodged and the horses were corralled in and around the old Spanish military barracks next to the Governors' Palace.

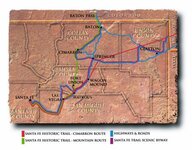

It was thought that in case of trouble the men should scurry up to the fort and defend the walls. As late as 1853, military inspector Col. Joseph Mansfield described Marcy as "the only real fort in the territory." Fort Union, located on the Santa Fe Trail east of Las Vegas, had been founded but was still a flimsy collection of huts.

Downriver, the Post of El Paso, founded on Sept. 28, 1849, briefly had six companies of the Third Infantry, but its soldiers were soon dispersed to other stations in southern New Mexico. Its substantial successor, Fort Bliss, did not come into being until 1854.

Since Marcy's troops were all quartered in town and there existed no threat of attack, the walls of the fort on the hill were allowed to deteriorate. Only the magazine continued in use, since it remained the safest place to keep powder, away from the townsfolk.

Santa Fe resident Marian Russell remembered that after Fort Marcy fell to ruin, local people used it for a burial ground. "One dear old lady, a Mrs. Sutton," she recalled, had a 19-year-old son buried in the fort. He had been a drummer boy in the Civil War. Coming home, he had been bitten by a mad dog on the streets of Santa Fe and died of hydrophobia. Daily Mrs. Sutton climbed the steep hill to Fort Marcy to place flowers or some little offering on her son's grave."

During 1887, a small incident occurred that must have severely impacted what was left of the fort. On Sept. 30, the Silver City Enterprise reported that a local citizen, Mrs. Tassie Wilson, had gone to the territorial capital for a visit. While there, she and friends had unearthed a trove of Spanish coins buried under the walls of old Fort Marcy.

The value of the find, said the Enterprise, was more than $2,300. The oldest coins were dated 1726 and 1740, and these had been donated to the Historical Society of New Mexico. And the paper added: "After the discovery was made, large numbers of Santa Fe citizens turned out and dug the whole country up in the vicinity of the fort, but without finding anything new." That frenzied treasure hunt must have destroyed the last of the standing walls.

In 1891, the government sold the Fort Marcy property at auction. The site on the hill was acquired by the city of Santa Fe in 1961, landscaped and turned into a scenic overlook. It is not well advertised or marked, and many visitors today miss this special place.

The remains of Fort Marcy on the hill above Santa Fe consist of mounds of earth several feet high tracing the outline of the adobe fortification. There is now an apartment complex NW of the remaining mounds. Photo shows the earthen mounds of Fort Marcy, atop Fort Marcy Hill.

This Certified Site of the Santa Fe National Historic Trail is located in the Santa Fe Historic District. The earthen fort was large enough to accommodate 1,000 soldiers. It was never completed and was abandoned in 1868. Fort Marcy symbolizes the Americn conquest. Situated on a hill above town, it was built by the US Army under Gen. Stephen W. Kearny in 1846 to protect the American presence in Santa Fe. It was the 1st military post in what later became the Mexican cession.

Location Information

View the Google Map for this site (lat-long decimal degrees, NAD27) 35.68950-105.93029

Paul Weideman

February 19, 2004

One of the treasures in the files (paper, not digital) at the Santa Fe City Hall is an historic-buildings survey entry on the old Hilario Gallegos House at 334 Otero Street.

The survey writers presented a history of the known owners of the home but went further, placing it in the context of an area of importance successively to American Indians, Spanish colonists and the American, Civil-War-era Army of the West.

The hill on which the house was built was an attractive dwelling site because of the cultivable land of a spring-fed ciŽnega (marsh) that once stretched from just east of present-day Washington Avenue all the way to the Santa Fe River. Archaeologists believe Indians lived in the area from about 1000 to 1350 A.D. By the 1630s the hill and cienega were the property of Diego de Moraga. Indians regained control of the hill during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680-92 and used the elevation advantage to fire upon the Spanish in the villa below.

Five years after the reconquest de Moragas granddaughter, Antonia de Moraga, built a torre—n (tower), likely on the site of an Indian kiva structure, and lived in it while she farmed the land.

Another early structure in the area was a garita (guardhouse) built in 1806. (This, along with an adjacent mortuary chapel and cemetery, were tourist attractions until well into the 20th century.) The strategic importance of the hill was immediately realized by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officers upon the arrival of Gen. Stephen Watts Kearnys army in Santa Fe in August of 1846, the year a quarter century of Mexican rule in New Mexico ended.

On May 13, 1846, the United States Congress declared war with Mexico, and three months later Kearny and his Army of the West marched along the Santa Fe Trail into New Mexicos undefended northern frontier, writes Robert Torrez in an online history of New Mexico. ...

General Kearny entered Santa Fe on Aug. 18, 1846, and took possession of New Mexico without firing a shot. It was a bloodless conquest, accomplished through diplomacy and guile, much as Diego de Vargas had done during the reconquista of 1692.

Fort Marcy, the adobe stronghold Kearny built on the hill, was large enough to accommodate 1,000 soldiers. The war with Mexico ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 but the fort served the Army again during the Civil War at least until early March 1862 when Union troops at Fort Marcy evacuated the capital as Confederate forces from Texas approached Santa Fe. For two weeks before a Union victory at Apache Canyon settled the local conflict, a Confederate flag flew over Santa Fes ancient Palace of the Governors.

Old maps of the Fort Marcy facilities show the fort situated on the hill near the present-day Cross of the Martyrs (not to be confused with the original cross off Paseo de la Loma) as well as a number of structures in the downtown area: the district headquarters where the Museum of Fine Arts now sits; officers and company quarters between Grant and Lincoln; and stables, corrals, blacksmith, commissary store and a mule shed between Lincoln and Washington.

According to stories related long ago by Hispanics living in the area, the venerable house on Otero was one of the oldest in Santa Fe and was partly built by Indians. Hilario Gallegos, a young farm laborer, owned it in the 1860s. Thirty years later part of the structure, which included several units, was owned by the Conway family, one of whose children, John Conway, went on to serve as county superintendent and school superintendent. Among his accomplishments was the building of 40 schoolhouses in the rural districts of Santa Fe County.

Before the construction of the Campanilla Compound condominiums on the site the historic-buildings survey notes that the cost of the condo complex included the loss of the homes architectural integrity and historic context the Hilario Gallegos House was a sprawling adobe structure with two sets of U-shaped wings enclosing placitas.

Another of the Otero Street adobes with a dramatic piece of 19th-century history is at 300 Otero. Juan and Apollonia Holmes bought the house in 1888. Juan was a deputy sheriff who was involved in an intriguing murder case.

On March 4, 1890, the Santa Fe Daily New Mexican reported the disappearance of a citizen named Faustin Ortiz. Nine days later the paper said rumors were spreading, that the town was frazzled, and that a man who had supposedly last seen Ortiz began crying and behaving insanely on the Plaza.

By March 25 Ortiz was presumed dead and a high Mass was celebrated for him. Three days later his badly beaten and shot body was discovered in an arroyo. The investigation led that August to a grand jury indicting Holmes, sheriff Francisco Chavez and six other prominent lawmakers in the murder.

The residential development of the area east of Bishops Lodge Road began in 1887 with a plan for villa residences called Fort Marcy Heights. The plan fell through, resurfacing in 1912 as 114 lots north and east of the Fort Marcy ruins; platted streets included Prince, Emory, Gilmer and MacLean.

The Garita Addition, begun in 1910, involved 22 lots on Garita Place and Magdalena Road. By 1933 more homes were being built on new streets named Artist, Sunset and Monte Vista. The southern edge of the neighborhood was redefined with the 1972 creation of Paseo de Peralta.

Fort Marcy Park has long served as the site of the annual burning of Zozobra or Old Man Gloom. The tall figure, created and festively tortured and burned each year by the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe, was conceived by artist Will Shuster in 1926.

................................

additional info

http://www.nmgs.org/artcuar6.htm