- Jun 27, 2004

- 551

- 1,007

Montezuma's Treasuire: An Essay

I wrote this a number of years ago as a final essay for a history class on The Spanish Borderlands that I had taken. In many ways the essay stands as a reflection, though much more brief, of a book I'm working on comprising the same topic. I would love your feedback on the essay, or the topic as a whole. Given the limitations of posting styles, indented long quotes are instead italicized...

--------------------------

Montezuma’s Treasure

The folklore of the American Southwest has been composed of a patchwork of traditions comprising the people and cultures of the region. One does not have to look far to see how stories of buried treasure and lost mines have played a vital role in weaving the fabric of the Southwest. The Lost Dutchman Mine, the Lost Adams Diggings, the Treasure of Victorio Peak, the San Saba Mine; regionally these stories evoke a sense of local identity, mysterious discourse and cultural flavor. The story of Montezuma’s Treasure is one of the American Southwest’s most prevalent legends: A vast hoard of gold and jewels carried out of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán and hidden to prevent the Spanish from acquiring it. Strangely the association of the treasure with Montezuma is in itself a historical misnomer. The Aztec emperor would have been dead when the treasure was carried from the city following the flight of the Spaniards in the wake of “Noche Triste,” or “Bad Night,” where the Spaniards slaughtered untold numbers of Aztecs, apparently without provocation. Historically Montezuma’s name is associated with the Spanish Conquest and it would seem his interactions with the Spanish, in particular Cortés, have forever associated Montezuma with the fabled treasure despite historical details to the contrary. Research reveals this merely one of many associations the Montezuma Treasure has with details that are not necessarily supported by history. But then again, history itself is often speculated about, especially in the last three decades where more emphasis has been placed on more holistic approaches to historical context rather than the one-sided accounts that tend to be most prevalent and solely represent the side of those with the power to propagate history. A good example of this is Montezuma, whose death remains a mystery despite what were likely hundreds of witnesses from both sides. The Spanish who’s version of history has been the most widely consumed for almost five centuries maintain that Montezuma was stoned to death by his own people, the Aztecs, however, reported that Montezuma was executed by the Spaniards via stabbing, hanging, or in some cases both. If historical details that should have been so easily recorded could be convoluted with the passage of time it is small wonder that something as mysterious as a buried treasure would likewise be shrouded in uncertainty centuries later. In the aftermath of the Spanish Conquest the Montezuma Treasure and the Spanish quest to reclaim it would plant the seeds of folklore throughout the Spanish territories. In time, these territories would change hands, ultimately becoming the United States Southwest, but these stories of lost treasure took root and flourish to this day as a defining characteristic of the folklore of the Southwest.

One of the few aspects of Montezuma’s Treasure that seems to be beyond dispute is the treasure itself. One of the major motivators for the Spanish expeditions into what is now Mexico was a quest for riches. The 1519 expedition of Hernán Cortés and approximately 600 soldiers would not be the first attempt by the Spanish to explore and ultimately secure what is now Mexico. Cortés’ expedition was the first of its type to result in the founding of a Spanish outpost. Establishing this outpost would serve as the foundation of what would ultimately culminate in the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec nation. Hearing of Emperor Montezuma (who is actually Montezuma II, but as the treasure legends are concerned Montezuma I has been relegated to obscurity) and gold he possesses, Cortés resigned himself to seeing the Emperor (and his riches) first hand. Montezuma was aware of the Spanish presence in the Aztec territories not long after and sent forth envoys. Cortés allied himself with tribes who were under the dominion of the Aztecs, and paid tribute by way of individuals that the Aztecs would use in human sacrifice as part of their religious rituals. Manipulating the tribes he encountered, Cortés made the best of this situation by promising to free these tribes from Aztec oppression in exchange for their support in overtaking Montezuma and the Aztec capital. Montezuma had plans of his own that did not include dealing directly with the Spanish. Montezuma’s envoys arrived with gifts for the strangers and a message from Montezuma himself. Richard Lee Marks describes a portion of this first distribution of gifts:

There was a calendar stone in gold, as big as the wheel of a cart, depicting the sun and its rays with many strange markings incised, and another wheel of highly polished silver depicting the moon. There were sculptures in gold of ducks, dogs, pumas, monkeys. There were ten magnificent and heavy gold collars, and gold necklaces inlaid with precious stones. …A bow and arrows were made of gold with even the bowstring in gold. The Spanish soldier’s guilt helmet, a little rustier than it used to be, was returned, filled with fine grains of gold. (62-63)

These gifts and many more were also presented with a message. Montezuma did not wish to meet with the Spanish and encouraged them to come no farther into the Aztec territory and that he (Montezuma) would not meet with the Spanish envoy. The Spanish would not be discouraged and despite the wishes of Montezuma continued their trek through the jungle, amassing allies as they went. Montezuma continued to ply the Spanish with gifts in hopes of turning them back but the unintended result was encouragement of the intrusion. Ultimately Montezuma resigned himself to meeting with the ever-growing party of Spanish party and their Native porters. Not long after the Spanish entered the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán through a series of political ventures and legal maneuverings the Spanish literally placed Montezuma under house arrest but managed to do so without jeopardizing their safety. While housed in Tenochtitlán the Spanish discovered recent masonry and plasterwork concealing a room full of treasure. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortés’ men present at the time, described the incident in his journals some year later:

When it was opened Cortés and some of his Captains went in first, and they saw such a number of jewels and slabs and plates of gold and chalchihuites and other great riches, that they were carried away and did not know what to say about such wealth. The news soon spread among all the other Captains and soldiers, and very secretly we went in to see it. When I saw it I marveled, and as at that time I was a youth and had never seen such riches as those in my life before, I took it for certain that there could not be another such store of wealth in the whole world. (226)

Cortés would later have vast amounts of gold ornaments and religious items melted down into ingots that could be transported more easily while he maintained his position in Tenochtitlán and plotted his next move.

As fate would have it Cortés would be called out of the city with a significant portion of his troops in response to the arrival (on the coast) of another group of Spanish sent to capture Cortés who had betrayed the Governor of Cuba, who had originally commissioned Cortés’ expedition in his own name. Pedro de Alvarado would be left in charge while Cortés went on to capture and assimilate this new party of soldiers, promising them gold for their allegiance. In his absence, Alvarado carried out a bloody massacre that would incite the Aztec people into rebellion against the Spanish. Cortés and his men returned to Tenochtitlán and managed to reunite with the besieged men he had left behind. With the Spanish were vastly outnumbered, Cortés made the decision to surrender the capital and retreat. With the hope of clearing a path, Cortés commanded Montezuma to speak to his people and encourage them to let the Spanish leave peacefully. It is during this time that Montezuma was killed, and as noted previously the details have been disputed ever since. Cortés and his men made a daring nighttime retreat from the city, carrying as much gold as they could. For many this gold was their undoing. Encumbered by the heavy metal and greed, one third of Cortés’ retreating force fell into the canals and drowned or were overtaken by the Aztecs and subsequently sacrificed. Miguel Leon-Portilla describes, in the Aztecs own words, their efforts to recover the gold from the bodies of the drowned Spanish soldiers: “…They recovered the gold ingots, the gold disks, the tubes of gold dust and the chalchihuite collars with their gold pendants. They gathered up everything they could find and searched the waters of the canal with the greatest of care.” (89) This event, tragic though it was, proved only a setback for the determined Cortés. In 1521 Cortés would finally conquer the Aztecs after laying siege to Tenochtitlán. The ravages of disease would lay waste the majority of Tenochtitlán vast populace, the rest would fall victim to starvation induced by the months-long siege. The Spanish then claimed Tenochtitlán and the Aztec territories in the name of the crown. The treasure they sought proved far more elusive than they could have imagined. William Prescott notes that, “The booty found there—that is, the treasures of gold and jewels, the only booty of much value in the eyes of the Spaniards—fell far below their expectations. …Yet the Aztecs must have been in possession of a much larger treasure, if it were only the wreck of that recovered from the Spaniards on the night of the memorable flight from Mexico.” (812)

Some have speculated Montezuma gave the order for the Aztec treasury and the recovered gold from the Spanish to be carried out of the city while Alvarado was in charge. It seems more likely, however, that one of Montezuma’s successors gave the order following his death and their ascension to the throne. This seems to be supported by written history of attempts by the Spanish to locate the missing gold following the capture of Tenochtitlán as Hugh Thomas notes:

…Alderete insisted that Cuauhtémoc and the King of Tacuba be put to the torture to provide information about the whereabouts of the missing gold. … Cuauhtémoc was tortured by being tied to a pole and having his feet (perhaps his hands) dipped in oil, which was then set, alight. The poor Emperor tried to hang himself first. The Castilians similarly treated Tetlepanquetzatzin, King of Tacuba. The latter kept an eye on Cuauhtémoc in the hope that he would have mercy on him and say something or give him leave to say what he knew. …Cuauhtémoc in the end confessed that the gods had told him some days before the fall of the city that defeat was inevitable. He had given orders for such gold as there was to be thrown into the lake. He made no other statement. Castilian divers went to look in the lake at the place where Cuauhtémoc said that the gold had been dropped. They found a few ornaments, but nothing substantial. (546)

Regardless of who ordered it, there is little doubt that a vast portion of a treasure the Spaniards had anticipated was absent upon their return. Carried from Tenochtitlán, this treasure would inspire and ultimately elude the Spanish who sought it. For the traditions and culture of the future American Southwest, an indelible mark was forever carved.

The stories that would sprout up in the wake of the fall of Tenochtitlán concerning the treasure began almost immediately and would spread with time over the face of the Southwest United States. First hand reports of the treasure’s movement are to date nonexistent, but the legend that has grown around the treasure is apparently self-sustaining. Despite no evidence to support the story, legend has it that 2,000 porters carried the vast Aztec hoard North from Tenochtitlán to be taken to the place from whence the Aztec originated, the land known as Aztlan. Some versions of the story refer to a trip that took the course of two moons (2 months) ending when the treasure was deposited in the Seven Caves known as Chicomoztoc. For the Aztec, Chicomoztoc represents the birthplace of seven tribes. From these tribes came the Aztec people who would settle the fabled Aztlan. Richard Townsend writes in reference to Chicomoztoc that, “The exact locations of these sites remain unclear, although there is agreement among some scholars that they lie somewhere between 60 and 180 miles to the northeast of the Valley of Mexico.” (57) Sixty to 180 miles from Mexico seems a much more feasible hiding place for a treasure, especially when compared to other proposed sites for the treasure (including but not limited to Utah). Some individuals have used the Chicomoztoc legend as a foundation to theorize that Montezuma’s Treasure is in fact secreted in seven separate locations. Connections might also be drawn between the idea of Chicomoztoc or the Seven Caves and the Spanish quest for Cibola, the Seven Cities of Gold. Coronoado sought these cities in what would be one of the grandest wild-goose chases in recorded history. The search for the Seven Cities of Gold yielded a humiliating truth, there was no gold and the cities fell far short of the Spanish expectations. Many in the treasure hunting community now argue that Coronado’s expedition was in fact a quest to recover Montezuma’s Treasure by attempting to retrace the steps of the supposed 2,000 porters and follow their path back to Aztlan. Writers site alleged oral traditions of Native Americans in the region that speak of a large group of strangers carrying gold. Unfortunately these writers never offer specifics in way of citations that can be properly investigated. The stories are further complicated, even when printed, by writers that omit details, invent dialogue (for the sake of story-telling), and take liberties to make stories seem more compelling or interesting.

From Sonora to Colorado, California to Texas, far flung communities separated by miles, geography, cultures and borders would lay claim to the legend of Montezuma’s Treasure and the idea that there’s was the place the treasure was buried. Some locations seem to have richer, deeper histories with the legend and thus lay a more “legitimate” claim despite the fact that no treasure has ever been recovered. One site in particular seems more unlikely than most, but has received more attention than all the others put together. That place is Kanab, Utah. The story itself achieved initial prominence in an October 1949 article by Maurine Whipple that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. Subsequent versions of the stories have appeared in Men’s magazines, Western Magazines, and Treasure Magazines…with each retelling the story seems to lose detail and reach a smaller audience. It’s fairly obvious by reading proceeding references that have cropped up in the proceeding decades that most of these other articles either draw heavily from the Whipple piece, or from other articles that themselves drew heavily from the Whipple piece. What follows is a very brief description of events that occurred in Kanab Utah and their relevance to the Montezuma Treasure story but the reader is encouraged to read the Whipple article for additional details, clarity, or specific reference points.

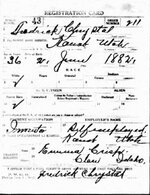

The story itself begins in 1914 with an enigmatic prospector named Freddie Crystal that resided at the Oscar Robinson Ranch. By all accounts Crystal did not work for the ranch but merely stayed there because the owner liked him. Crystal apparently made no secret that he was looking for Montezuma’s Treasure and believed it was in the Kanab region based on the presence of certain Indian petroglyphs he felt were clues to the treasure’s location. Eventually Crystal narrowed his search to a specific region known as Johnson’s Canyon where the symbols were present but that more information was needed to uncover the treasures final resting point. In 1916 Freddie Crystal disappeared with no fanfare and to the relief of the ranch hands who felt he was a freeloader. Four years later Freddie Crystal reappeared at the Robinson Ranch as abruptly as he had disappeared and was immediately welcomed back by Robinson. Freddie claimed that in the last four years he had traveled to Mexico and had discovered a 400 year-old map in a monastery that led to the fabled Montezuma Treasure. Amidst the ridicule of the ranch-hands who taunted Crystal, he again set out to find the treasure, this time by matching land features in the area with those on the map. It would take two years for Crystal to make the connection between a ring of mountains depicted in the map and the landmarks themselves but when he did the mood of the townspeople changed rather quickly (not to mention positively). The maps called for a series of steps cut into the side of a particular mountain, White Mountain, and upon investigation the steps were indeed found. Rough-hewn, the steps cut a clear path up a steep grade. Following the steps, Crystal and several of the ranch hands found the steps led to a wall that would later be determined to be man made. Digging into the wall with pocketknives, the men broke into a chamber that led deep inside the mountain. The plug proved to be the first of many similar plugs composed, it is said, of blue limestone bricks not native to the region. In the coming weeks the townspeople (by accounts most all of them) began to help by transporting materials, food, and water 20 miles, the distance from White Mountain to the city of Kanab. Keeping the story secret from outsiders was a fairly easy undertaking; in 1922 Kanab, Utah was the most remote city in the continental United States. The town council allegedly made it illegal to say the word “treasure” in public and imposed a stiff fine for those who violated this regulation. Sixty feet into the mountain a chamber with multiple passages was revealed but no treasure. Excavations continued for two years as the townspeople cleared out tunnels of sand, dirt and rubble revealing what is described as a “honeycomb of passages,” but still no treasure. The townspeople began to lose faith, despite the evidences that led Crystal to the site in the first place. Crystal himself began to suspect the tunnel had been a decoy and that the real entrance to the treasure vault was now buried at the base of the mountain by the fill they had removed. Disillusioned by the treasure that eluded him, and abandoned by the people who had assisted him for two years, Crystal disappeared leaving a legacy of unrealized riches and en enduring mystery. Subsequent retellings of this story have been indulged considerably by the authors, most notably by the inclusion of alleged booby-traps the townspeople encountered. Large stones on counter balances, deep pits, and secret passages allegedly greeted those digging for the treasure. Whipple makes no mention of these in her original story, although a visit to the site even now does in fact reveal several vertical shafts of considerable depth that could quite easily be fallen into. Whether these were present during the 1922 digs or were dug out since the initial discovery of the cave is uncertain.

The most enduring argument against the notion that the Aztecs might have moved a vast depository to Utah from Mexico is simple logistics. The distance involved, the time it would take, and the man power when tied in with the basic motive: Why would the Aztecs go to all this trouble? To the determined treasure hunter, these realities are often brushed aside, glossed over, or merely denied. Basing a treasure search on a minimal amount of historical fact and a generous amount of legend and lore leaves a lot of room for invented evidences. Once born, stories of this type (i.e. treasure) tend to take on a life of their own as details are picked up along the way with little emphasis placed on reality, and in some cases logic. Despite these realities many have searched for Montezuma’s Treasure based on the premise that the Aztec treasure was returned to the homeland known as Aztlan. For treasure hunters the plan is simple: Find Aztlan and you find the treasure. Much like the treasure, however, Aztlan has proved elusive. Separating the historical Aztlan from the legendary one passed on orally is not only difficult in itself, but is complicated by the source material which was largely transcribed five centuries ago from a native spoken language to a foreign written tongue. Add to this the fact that the Aztecs providing this information likely made no distinction between legend and fact because the story teller would have likely believed his stories to be the truth with little regard (or need to regard) the validity or the origins of the material.

The treasure hunting community has received some vindication in the last ten years as research has come forth that strongly suggests the Aztecs may have in fact migrated from Utah. A recent newspaper article by Tim Sullivan describes attempts by various historians to promote the idea that Utah is indeed the ancestral home of the Aztecs. These scholars cite 18th and 19th Century maps which indicate the Utah region has been designated as Aztlan. In particular the 1847 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo map that identifies the Utah region as the “Ancient Homeland of the Aztecs.” Sullivan also writes, “Researchers also cite the close connection between the languages of the Aztecs and the Ute Indians in the “Uto-Aztecan” linguistic group, as well as the coincidence that the Anasazi culture began to decline at about the same time the Aztecs’ ancestors may have moved north before moving south.” (1) Time will tell what other evidences emerge that will support or refute the notion of the Utah-Aztlan connection, for now Aztlan is a mystery contested every bit as much as the resting place of Montezuma’s Treasure. Guy E. Powell provides what he describes as, “…a rough list of some of the distinguishing features of Aztlan, taken from Indian records and legends. (4) The list is composed of 44 items, none of which include specific citations or references. For the sake of space only a partial list follows where specific details could possibly reflect aspects of the Salt Lake, Utah region, and thus lend credence to the notion that Utah may in fact be the Aztecs ancestral home of Aztlan:

1. Aztlan was a shallow lake area, with many smaller lakes in the valley.

3. The area was covered with reeds. (One of the names the Aztecs gave the lake was Reed Sea.)

4. The area was the home of blue herons. (The Aztecs called Aztlan the Heron Place.)

5. The area was inhabited by cranes. (The Aztecs called themselves the Crane People.)

11. There were three migrations prompted by the lake’s receding three times. (There are three lake levels evident)

13. At Aztlan was Chicimorto, the Place of the Seven Caves of Grottoes.

15. The Place of the Seven Caves was located on an island in a lake area.

(5)

It is important to note that when Powell composed this list he was actually referring to a site in Texas that he felt was the location of Aztlan and the premise of this book is to support this theory. However, as is demonstrated by the above list, many of his descriptors are fairly vague or are composed of things one would naturally expect in similar regions (i.e. reeds in a lake area) so the evidence is far from compelling. However, if one assumes his list of Aztlan features has merit (and in the absence of quoted source material the list’s merit is debatable), then much of the evidence could be applied to the Salt Lake region, or various other Utah regions (or non-Utah regions) for that matter.

Montezuma County, Colorado; Cortez, Colorado; Cibola County, New Mexico; Aztec, New Mexico; Montezuma’s Castle and Montezuma’s Well, Arizona; Montezuma Creek, Utah: The United States Southwest is replete with place names that reflect the founder’s fascination with the Spanish Conquest and the Aztec people. While the origins of these place names might be lost (or in some cases found with some investigation) there is little doubt that over the decades and even centuries these names have evoked nostalgia, a sense of adventure, and American’s fascination with the people, places, and events that shaped the American continent. Add to this the lure of quick and vast riches for the taking. This idea motivated the conquistadors and three centuries later would open up much of the United States West as the California Gold Rush gripped the nation. Unique people and cultures separated by vast periods of time are amalgamated as these stories create a sense of unity. Diverse peoples converge due to a common thread. The Native American protecting his land, the Spanish Friar, the Mexican Miner, and the late-comer, the American Cowboy; all linked with their own agenda, identity and history. Each adds to the lore, both in detail and in the preservation and distribution of these stories. These stories continue to influence us in this modern era where treasures and mines seem more like fairy-tales than folktales; where the participants in the stories seem like little more than ghostly stereotypes. Not only has the history and lore been embraced, but so have the legends and their influence on American society and culture. Most recently the notion of Aztec treasure (and the search for it) was glamorized in the motion picture, “Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.” Some years ago one of the most popular computer video game titles involved the adventures of Panama Jack and his attempts to recover Aztec Gold in, “Montezuma’s Revenge.” As a cultural influence, many travelers are aware of the colloquial phrase Montezuma’s Revenge, which refers to Dysentery, a sickness often associated with Mexican drinking water. A lesser-known figure of speech, “holding your feet to the fire,” is a direct reference to the tortures suffered by Cuauhtémoc at the hands of the Spanish. Stories of Montezuma’s Gold have persisted for almost five centuries and in that time these stories regarding the treasure’s ultimate resting place have spread far and wide. How these stories began is often as big a mystery as the treasure itself. The fact that at least 50 different locations have been proposed throughout North America seems to matter little to those who are determined to believe their own proposed location is in fact the correct one. To date no major Aztec treasure associated with Montezuma’s hoard has been reported found despite years of searching and countless man hours dedicated to the endeavor. To those who embrace the legends as fact, the failure thus far of the treasure to be discovered serves only to motivate based on the belief that the treasure still remains hidden, waiting to be found. In the absence of treasure, however, one could argue that these tales, legends and their legacy are the true treasure and have long since been found.

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico. Ed. Genaro Garcia.

Trans. A. P. Maudslay. Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1956.

Leon-Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of

Mexico. Trans. Lysander Kemp. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1990.

Marks, Richard Lee. Cortés: The Great Adventurer and the Fate of Aztec Mexico.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1993.

Powell, Guy E. Latest Aztec Discoveries: Origin and Untold Riches. San Antonio, TX:

The Naylor Company, 1970.

Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Mexico. New York: The Modern

Library, 2001.

Sullivan, Tim. “Bits of History Suggest Utah is Location of Mythic Aztlan.” The Salt

Lake Tribune 17 November 2002: 1-2.

Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York:

Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Townsend, Richard F. The Aztecs. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1992.

Whipple, Maurine. “Anybody’s Gold Mine.” The Saturday Evening Post 1 Oct. 1949:

21-22, 102-103, 105-106, 108.

I wrote this a number of years ago as a final essay for a history class on The Spanish Borderlands that I had taken. In many ways the essay stands as a reflection, though much more brief, of a book I'm working on comprising the same topic. I would love your feedback on the essay, or the topic as a whole. Given the limitations of posting styles, indented long quotes are instead italicized...

--------------------------

The Origin, Evolution and Impact of Folklore:

Montezuma’s Treasure

The folklore of the American Southwest has been composed of a patchwork of traditions comprising the people and cultures of the region. One does not have to look far to see how stories of buried treasure and lost mines have played a vital role in weaving the fabric of the Southwest. The Lost Dutchman Mine, the Lost Adams Diggings, the Treasure of Victorio Peak, the San Saba Mine; regionally these stories evoke a sense of local identity, mysterious discourse and cultural flavor. The story of Montezuma’s Treasure is one of the American Southwest’s most prevalent legends: A vast hoard of gold and jewels carried out of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán and hidden to prevent the Spanish from acquiring it. Strangely the association of the treasure with Montezuma is in itself a historical misnomer. The Aztec emperor would have been dead when the treasure was carried from the city following the flight of the Spaniards in the wake of “Noche Triste,” or “Bad Night,” where the Spaniards slaughtered untold numbers of Aztecs, apparently without provocation. Historically Montezuma’s name is associated with the Spanish Conquest and it would seem his interactions with the Spanish, in particular Cortés, have forever associated Montezuma with the fabled treasure despite historical details to the contrary. Research reveals this merely one of many associations the Montezuma Treasure has with details that are not necessarily supported by history. But then again, history itself is often speculated about, especially in the last three decades where more emphasis has been placed on more holistic approaches to historical context rather than the one-sided accounts that tend to be most prevalent and solely represent the side of those with the power to propagate history. A good example of this is Montezuma, whose death remains a mystery despite what were likely hundreds of witnesses from both sides. The Spanish who’s version of history has been the most widely consumed for almost five centuries maintain that Montezuma was stoned to death by his own people, the Aztecs, however, reported that Montezuma was executed by the Spaniards via stabbing, hanging, or in some cases both. If historical details that should have been so easily recorded could be convoluted with the passage of time it is small wonder that something as mysterious as a buried treasure would likewise be shrouded in uncertainty centuries later. In the aftermath of the Spanish Conquest the Montezuma Treasure and the Spanish quest to reclaim it would plant the seeds of folklore throughout the Spanish territories. In time, these territories would change hands, ultimately becoming the United States Southwest, but these stories of lost treasure took root and flourish to this day as a defining characteristic of the folklore of the Southwest.

One of the few aspects of Montezuma’s Treasure that seems to be beyond dispute is the treasure itself. One of the major motivators for the Spanish expeditions into what is now Mexico was a quest for riches. The 1519 expedition of Hernán Cortés and approximately 600 soldiers would not be the first attempt by the Spanish to explore and ultimately secure what is now Mexico. Cortés’ expedition was the first of its type to result in the founding of a Spanish outpost. Establishing this outpost would serve as the foundation of what would ultimately culminate in the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec nation. Hearing of Emperor Montezuma (who is actually Montezuma II, but as the treasure legends are concerned Montezuma I has been relegated to obscurity) and gold he possesses, Cortés resigned himself to seeing the Emperor (and his riches) first hand. Montezuma was aware of the Spanish presence in the Aztec territories not long after and sent forth envoys. Cortés allied himself with tribes who were under the dominion of the Aztecs, and paid tribute by way of individuals that the Aztecs would use in human sacrifice as part of their religious rituals. Manipulating the tribes he encountered, Cortés made the best of this situation by promising to free these tribes from Aztec oppression in exchange for their support in overtaking Montezuma and the Aztec capital. Montezuma had plans of his own that did not include dealing directly with the Spanish. Montezuma’s envoys arrived with gifts for the strangers and a message from Montezuma himself. Richard Lee Marks describes a portion of this first distribution of gifts:

There was a calendar stone in gold, as big as the wheel of a cart, depicting the sun and its rays with many strange markings incised, and another wheel of highly polished silver depicting the moon. There were sculptures in gold of ducks, dogs, pumas, monkeys. There were ten magnificent and heavy gold collars, and gold necklaces inlaid with precious stones. …A bow and arrows were made of gold with even the bowstring in gold. The Spanish soldier’s guilt helmet, a little rustier than it used to be, was returned, filled with fine grains of gold. (62-63)

These gifts and many more were also presented with a message. Montezuma did not wish to meet with the Spanish and encouraged them to come no farther into the Aztec territory and that he (Montezuma) would not meet with the Spanish envoy. The Spanish would not be discouraged and despite the wishes of Montezuma continued their trek through the jungle, amassing allies as they went. Montezuma continued to ply the Spanish with gifts in hopes of turning them back but the unintended result was encouragement of the intrusion. Ultimately Montezuma resigned himself to meeting with the ever-growing party of Spanish party and their Native porters. Not long after the Spanish entered the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán through a series of political ventures and legal maneuverings the Spanish literally placed Montezuma under house arrest but managed to do so without jeopardizing their safety. While housed in Tenochtitlán the Spanish discovered recent masonry and plasterwork concealing a room full of treasure. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortés’ men present at the time, described the incident in his journals some year later:

When it was opened Cortés and some of his Captains went in first, and they saw such a number of jewels and slabs and plates of gold and chalchihuites and other great riches, that they were carried away and did not know what to say about such wealth. The news soon spread among all the other Captains and soldiers, and very secretly we went in to see it. When I saw it I marveled, and as at that time I was a youth and had never seen such riches as those in my life before, I took it for certain that there could not be another such store of wealth in the whole world. (226)

Cortés would later have vast amounts of gold ornaments and religious items melted down into ingots that could be transported more easily while he maintained his position in Tenochtitlán and plotted his next move.

As fate would have it Cortés would be called out of the city with a significant portion of his troops in response to the arrival (on the coast) of another group of Spanish sent to capture Cortés who had betrayed the Governor of Cuba, who had originally commissioned Cortés’ expedition in his own name. Pedro de Alvarado would be left in charge while Cortés went on to capture and assimilate this new party of soldiers, promising them gold for their allegiance. In his absence, Alvarado carried out a bloody massacre that would incite the Aztec people into rebellion against the Spanish. Cortés and his men returned to Tenochtitlán and managed to reunite with the besieged men he had left behind. With the Spanish were vastly outnumbered, Cortés made the decision to surrender the capital and retreat. With the hope of clearing a path, Cortés commanded Montezuma to speak to his people and encourage them to let the Spanish leave peacefully. It is during this time that Montezuma was killed, and as noted previously the details have been disputed ever since. Cortés and his men made a daring nighttime retreat from the city, carrying as much gold as they could. For many this gold was their undoing. Encumbered by the heavy metal and greed, one third of Cortés’ retreating force fell into the canals and drowned or were overtaken by the Aztecs and subsequently sacrificed. Miguel Leon-Portilla describes, in the Aztecs own words, their efforts to recover the gold from the bodies of the drowned Spanish soldiers: “…They recovered the gold ingots, the gold disks, the tubes of gold dust and the chalchihuite collars with their gold pendants. They gathered up everything they could find and searched the waters of the canal with the greatest of care.” (89) This event, tragic though it was, proved only a setback for the determined Cortés. In 1521 Cortés would finally conquer the Aztecs after laying siege to Tenochtitlán. The ravages of disease would lay waste the majority of Tenochtitlán vast populace, the rest would fall victim to starvation induced by the months-long siege. The Spanish then claimed Tenochtitlán and the Aztec territories in the name of the crown. The treasure they sought proved far more elusive than they could have imagined. William Prescott notes that, “The booty found there—that is, the treasures of gold and jewels, the only booty of much value in the eyes of the Spaniards—fell far below their expectations. …Yet the Aztecs must have been in possession of a much larger treasure, if it were only the wreck of that recovered from the Spaniards on the night of the memorable flight from Mexico.” (812)

Some have speculated Montezuma gave the order for the Aztec treasury and the recovered gold from the Spanish to be carried out of the city while Alvarado was in charge. It seems more likely, however, that one of Montezuma’s successors gave the order following his death and their ascension to the throne. This seems to be supported by written history of attempts by the Spanish to locate the missing gold following the capture of Tenochtitlán as Hugh Thomas notes:

…Alderete insisted that Cuauhtémoc and the King of Tacuba be put to the torture to provide information about the whereabouts of the missing gold. … Cuauhtémoc was tortured by being tied to a pole and having his feet (perhaps his hands) dipped in oil, which was then set, alight. The poor Emperor tried to hang himself first. The Castilians similarly treated Tetlepanquetzatzin, King of Tacuba. The latter kept an eye on Cuauhtémoc in the hope that he would have mercy on him and say something or give him leave to say what he knew. …Cuauhtémoc in the end confessed that the gods had told him some days before the fall of the city that defeat was inevitable. He had given orders for such gold as there was to be thrown into the lake. He made no other statement. Castilian divers went to look in the lake at the place where Cuauhtémoc said that the gold had been dropped. They found a few ornaments, but nothing substantial. (546)

Regardless of who ordered it, there is little doubt that a vast portion of a treasure the Spaniards had anticipated was absent upon their return. Carried from Tenochtitlán, this treasure would inspire and ultimately elude the Spanish who sought it. For the traditions and culture of the future American Southwest, an indelible mark was forever carved.

The stories that would sprout up in the wake of the fall of Tenochtitlán concerning the treasure began almost immediately and would spread with time over the face of the Southwest United States. First hand reports of the treasure’s movement are to date nonexistent, but the legend that has grown around the treasure is apparently self-sustaining. Despite no evidence to support the story, legend has it that 2,000 porters carried the vast Aztec hoard North from Tenochtitlán to be taken to the place from whence the Aztec originated, the land known as Aztlan. Some versions of the story refer to a trip that took the course of two moons (2 months) ending when the treasure was deposited in the Seven Caves known as Chicomoztoc. For the Aztec, Chicomoztoc represents the birthplace of seven tribes. From these tribes came the Aztec people who would settle the fabled Aztlan. Richard Townsend writes in reference to Chicomoztoc that, “The exact locations of these sites remain unclear, although there is agreement among some scholars that they lie somewhere between 60 and 180 miles to the northeast of the Valley of Mexico.” (57) Sixty to 180 miles from Mexico seems a much more feasible hiding place for a treasure, especially when compared to other proposed sites for the treasure (including but not limited to Utah). Some individuals have used the Chicomoztoc legend as a foundation to theorize that Montezuma’s Treasure is in fact secreted in seven separate locations. Connections might also be drawn between the idea of Chicomoztoc or the Seven Caves and the Spanish quest for Cibola, the Seven Cities of Gold. Coronoado sought these cities in what would be one of the grandest wild-goose chases in recorded history. The search for the Seven Cities of Gold yielded a humiliating truth, there was no gold and the cities fell far short of the Spanish expectations. Many in the treasure hunting community now argue that Coronado’s expedition was in fact a quest to recover Montezuma’s Treasure by attempting to retrace the steps of the supposed 2,000 porters and follow their path back to Aztlan. Writers site alleged oral traditions of Native Americans in the region that speak of a large group of strangers carrying gold. Unfortunately these writers never offer specifics in way of citations that can be properly investigated. The stories are further complicated, even when printed, by writers that omit details, invent dialogue (for the sake of story-telling), and take liberties to make stories seem more compelling or interesting.

From Sonora to Colorado, California to Texas, far flung communities separated by miles, geography, cultures and borders would lay claim to the legend of Montezuma’s Treasure and the idea that there’s was the place the treasure was buried. Some locations seem to have richer, deeper histories with the legend and thus lay a more “legitimate” claim despite the fact that no treasure has ever been recovered. One site in particular seems more unlikely than most, but has received more attention than all the others put together. That place is Kanab, Utah. The story itself achieved initial prominence in an October 1949 article by Maurine Whipple that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. Subsequent versions of the stories have appeared in Men’s magazines, Western Magazines, and Treasure Magazines…with each retelling the story seems to lose detail and reach a smaller audience. It’s fairly obvious by reading proceeding references that have cropped up in the proceeding decades that most of these other articles either draw heavily from the Whipple piece, or from other articles that themselves drew heavily from the Whipple piece. What follows is a very brief description of events that occurred in Kanab Utah and their relevance to the Montezuma Treasure story but the reader is encouraged to read the Whipple article for additional details, clarity, or specific reference points.

The story itself begins in 1914 with an enigmatic prospector named Freddie Crystal that resided at the Oscar Robinson Ranch. By all accounts Crystal did not work for the ranch but merely stayed there because the owner liked him. Crystal apparently made no secret that he was looking for Montezuma’s Treasure and believed it was in the Kanab region based on the presence of certain Indian petroglyphs he felt were clues to the treasure’s location. Eventually Crystal narrowed his search to a specific region known as Johnson’s Canyon where the symbols were present but that more information was needed to uncover the treasures final resting point. In 1916 Freddie Crystal disappeared with no fanfare and to the relief of the ranch hands who felt he was a freeloader. Four years later Freddie Crystal reappeared at the Robinson Ranch as abruptly as he had disappeared and was immediately welcomed back by Robinson. Freddie claimed that in the last four years he had traveled to Mexico and had discovered a 400 year-old map in a monastery that led to the fabled Montezuma Treasure. Amidst the ridicule of the ranch-hands who taunted Crystal, he again set out to find the treasure, this time by matching land features in the area with those on the map. It would take two years for Crystal to make the connection between a ring of mountains depicted in the map and the landmarks themselves but when he did the mood of the townspeople changed rather quickly (not to mention positively). The maps called for a series of steps cut into the side of a particular mountain, White Mountain, and upon investigation the steps were indeed found. Rough-hewn, the steps cut a clear path up a steep grade. Following the steps, Crystal and several of the ranch hands found the steps led to a wall that would later be determined to be man made. Digging into the wall with pocketknives, the men broke into a chamber that led deep inside the mountain. The plug proved to be the first of many similar plugs composed, it is said, of blue limestone bricks not native to the region. In the coming weeks the townspeople (by accounts most all of them) began to help by transporting materials, food, and water 20 miles, the distance from White Mountain to the city of Kanab. Keeping the story secret from outsiders was a fairly easy undertaking; in 1922 Kanab, Utah was the most remote city in the continental United States. The town council allegedly made it illegal to say the word “treasure” in public and imposed a stiff fine for those who violated this regulation. Sixty feet into the mountain a chamber with multiple passages was revealed but no treasure. Excavations continued for two years as the townspeople cleared out tunnels of sand, dirt and rubble revealing what is described as a “honeycomb of passages,” but still no treasure. The townspeople began to lose faith, despite the evidences that led Crystal to the site in the first place. Crystal himself began to suspect the tunnel had been a decoy and that the real entrance to the treasure vault was now buried at the base of the mountain by the fill they had removed. Disillusioned by the treasure that eluded him, and abandoned by the people who had assisted him for two years, Crystal disappeared leaving a legacy of unrealized riches and en enduring mystery. Subsequent retellings of this story have been indulged considerably by the authors, most notably by the inclusion of alleged booby-traps the townspeople encountered. Large stones on counter balances, deep pits, and secret passages allegedly greeted those digging for the treasure. Whipple makes no mention of these in her original story, although a visit to the site even now does in fact reveal several vertical shafts of considerable depth that could quite easily be fallen into. Whether these were present during the 1922 digs or were dug out since the initial discovery of the cave is uncertain.

The most enduring argument against the notion that the Aztecs might have moved a vast depository to Utah from Mexico is simple logistics. The distance involved, the time it would take, and the man power when tied in with the basic motive: Why would the Aztecs go to all this trouble? To the determined treasure hunter, these realities are often brushed aside, glossed over, or merely denied. Basing a treasure search on a minimal amount of historical fact and a generous amount of legend and lore leaves a lot of room for invented evidences. Once born, stories of this type (i.e. treasure) tend to take on a life of their own as details are picked up along the way with little emphasis placed on reality, and in some cases logic. Despite these realities many have searched for Montezuma’s Treasure based on the premise that the Aztec treasure was returned to the homeland known as Aztlan. For treasure hunters the plan is simple: Find Aztlan and you find the treasure. Much like the treasure, however, Aztlan has proved elusive. Separating the historical Aztlan from the legendary one passed on orally is not only difficult in itself, but is complicated by the source material which was largely transcribed five centuries ago from a native spoken language to a foreign written tongue. Add to this the fact that the Aztecs providing this information likely made no distinction between legend and fact because the story teller would have likely believed his stories to be the truth with little regard (or need to regard) the validity or the origins of the material.

The treasure hunting community has received some vindication in the last ten years as research has come forth that strongly suggests the Aztecs may have in fact migrated from Utah. A recent newspaper article by Tim Sullivan describes attempts by various historians to promote the idea that Utah is indeed the ancestral home of the Aztecs. These scholars cite 18th and 19th Century maps which indicate the Utah region has been designated as Aztlan. In particular the 1847 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo map that identifies the Utah region as the “Ancient Homeland of the Aztecs.” Sullivan also writes, “Researchers also cite the close connection between the languages of the Aztecs and the Ute Indians in the “Uto-Aztecan” linguistic group, as well as the coincidence that the Anasazi culture began to decline at about the same time the Aztecs’ ancestors may have moved north before moving south.” (1) Time will tell what other evidences emerge that will support or refute the notion of the Utah-Aztlan connection, for now Aztlan is a mystery contested every bit as much as the resting place of Montezuma’s Treasure. Guy E. Powell provides what he describes as, “…a rough list of some of the distinguishing features of Aztlan, taken from Indian records and legends. (4) The list is composed of 44 items, none of which include specific citations or references. For the sake of space only a partial list follows where specific details could possibly reflect aspects of the Salt Lake, Utah region, and thus lend credence to the notion that Utah may in fact be the Aztecs ancestral home of Aztlan:

1. Aztlan was a shallow lake area, with many smaller lakes in the valley.

3. The area was covered with reeds. (One of the names the Aztecs gave the lake was Reed Sea.)

4. The area was the home of blue herons. (The Aztecs called Aztlan the Heron Place.)

5. The area was inhabited by cranes. (The Aztecs called themselves the Crane People.)

11. There were three migrations prompted by the lake’s receding three times. (There are three lake levels evident)

13. At Aztlan was Chicimorto, the Place of the Seven Caves of Grottoes.

15. The Place of the Seven Caves was located on an island in a lake area.

(5)

It is important to note that when Powell composed this list he was actually referring to a site in Texas that he felt was the location of Aztlan and the premise of this book is to support this theory. However, as is demonstrated by the above list, many of his descriptors are fairly vague or are composed of things one would naturally expect in similar regions (i.e. reeds in a lake area) so the evidence is far from compelling. However, if one assumes his list of Aztlan features has merit (and in the absence of quoted source material the list’s merit is debatable), then much of the evidence could be applied to the Salt Lake region, or various other Utah regions (or non-Utah regions) for that matter.

Montezuma County, Colorado; Cortez, Colorado; Cibola County, New Mexico; Aztec, New Mexico; Montezuma’s Castle and Montezuma’s Well, Arizona; Montezuma Creek, Utah: The United States Southwest is replete with place names that reflect the founder’s fascination with the Spanish Conquest and the Aztec people. While the origins of these place names might be lost (or in some cases found with some investigation) there is little doubt that over the decades and even centuries these names have evoked nostalgia, a sense of adventure, and American’s fascination with the people, places, and events that shaped the American continent. Add to this the lure of quick and vast riches for the taking. This idea motivated the conquistadors and three centuries later would open up much of the United States West as the California Gold Rush gripped the nation. Unique people and cultures separated by vast periods of time are amalgamated as these stories create a sense of unity. Diverse peoples converge due to a common thread. The Native American protecting his land, the Spanish Friar, the Mexican Miner, and the late-comer, the American Cowboy; all linked with their own agenda, identity and history. Each adds to the lore, both in detail and in the preservation and distribution of these stories. These stories continue to influence us in this modern era where treasures and mines seem more like fairy-tales than folktales; where the participants in the stories seem like little more than ghostly stereotypes. Not only has the history and lore been embraced, but so have the legends and their influence on American society and culture. Most recently the notion of Aztec treasure (and the search for it) was glamorized in the motion picture, “Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.” Some years ago one of the most popular computer video game titles involved the adventures of Panama Jack and his attempts to recover Aztec Gold in, “Montezuma’s Revenge.” As a cultural influence, many travelers are aware of the colloquial phrase Montezuma’s Revenge, which refers to Dysentery, a sickness often associated with Mexican drinking water. A lesser-known figure of speech, “holding your feet to the fire,” is a direct reference to the tortures suffered by Cuauhtémoc at the hands of the Spanish. Stories of Montezuma’s Gold have persisted for almost five centuries and in that time these stories regarding the treasure’s ultimate resting place have spread far and wide. How these stories began is often as big a mystery as the treasure itself. The fact that at least 50 different locations have been proposed throughout North America seems to matter little to those who are determined to believe their own proposed location is in fact the correct one. To date no major Aztec treasure associated with Montezuma’s hoard has been reported found despite years of searching and countless man hours dedicated to the endeavor. To those who embrace the legends as fact, the failure thus far of the treasure to be discovered serves only to motivate based on the belief that the treasure still remains hidden, waiting to be found. In the absence of treasure, however, one could argue that these tales, legends and their legacy are the true treasure and have long since been found.

Works Cited

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico. Ed. Genaro Garcia.

Trans. A. P. Maudslay. Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1956.

Leon-Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of

Mexico. Trans. Lysander Kemp. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1990.

Marks, Richard Lee. Cortés: The Great Adventurer and the Fate of Aztec Mexico.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1993.

Powell, Guy E. Latest Aztec Discoveries: Origin and Untold Riches. San Antonio, TX:

The Naylor Company, 1970.

Prescott, William H. History of the Conquest of Mexico. New York: The Modern

Library, 2001.

Sullivan, Tim. “Bits of History Suggest Utah is Location of Mythic Aztlan.” The Salt

Lake Tribune 17 November 2002: 1-2.

Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico. New York:

Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Townsend, Richard F. The Aztecs. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1992.

Whipple, Maurine. “Anybody’s Gold Mine.” The Saturday Evening Post 1 Oct. 1949:

21-22, 102-103, 105-106, 108.

Last edited: