Gypsy Heart

Gold Member

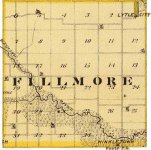

Lytle City: Fillmore Township, Section 1. Robert B. Lytle laid out an ambitious town on June 23, 1857. The town grew to substance through the 1870’s. By 1881, it had declined, and at that time contained a hotel, general store, blacksmith, wagon shop, post office, two physicians, shoemaker, carpenter, a school, and a handful of houses. When a north-south railroad was established through the county, a town was born two miles west of Lytle City. In 1884, the people of the little Irish town of Lytle City moved residences, stores, buildings, and families to where the railroad was beginning. The new town of Parnell (first called Callan) quickly lured residents and businesses away from Lytle City, which completely disappeared.

The following is abstracted from a serial that was published in January and February of 1936 in the Williamsburg Journal-Tribune and was printed in The Palimpsest, a monthly magazine of the State Historical Society of Iowa. The original was written by Harry Eugene Kelly.

Lytle City was a village in Fillmore Township, Iowa County, Iowa, located in 1857, in anticipation of the coming of a railroad. In 1884, the town ceased to exist.

When the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad (later to become a part of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad) was about to be constructed between Iowa City and Des Moines, John Lytle and his sons, Robert Bryce Lytle and Lionel Branson Lytle, of Solon, Iowa, originally from Licking County, Ohio decided to build a town site on the proposed railroad route. The site chosen was on a line between Iowa City and Des Moines, about twenty-five miles nearly straight west of Iowa City, where they thought the projected railroad would be built.

On June 24, 1857, a plat of the town site under the name of "Lytle City", and dated June 23, 1857, was filed in the recorder's office at Marengo, under the authority of the leader of the enterprise, Robert B. Lytle (erroneously written Robert "T" Lytle on the official record).

The official description of the land was the southwest quarter and the northwest quarter, of the northeast quarter of section one of township seventy-eight north, of range ten.

The three founders and their families settled and began enthusiastically to develop their project. They immediately erected some wooden dwelling houses and a stone building and opened a general store.

The town grew quickly and the population, never much over one hundred residents, soon included a blacksmith, a shoemaker, a carpenter, a wagon maker, a plasterer, a saloon keeper, and several merchants. They all lived hopefully in the expectation of enjoying great benefit from the coming railroad.

Robert B. Lytle, left before 1860 for ventures in other places, especially in the region of Sioux City; and his father, John Lytle, went to southern Iowa. Lionel Branson Lytle stayed on as the proprietor of the general store. He died in 1868, leaving his widow, three daughters, and three sons.

Lytle City had one Negro in its population, a boy named Bell, who kept the doctor's horses. The local doctor, George Welsh, a Canadian, was a graduate of the medical college of the State University of Michigan. He was the only man of science and substantial education in the place and his learning was held in great respect.

Lytle City was never incorporated. It had no town officers, no policeman, no jail, no town hall, no public meeting place, no theater, no church, no newspaper, no library, no hotel, no public lighting system for buildings or streets, no undertaker, no cemetery, no livery stable, no barber shop, and no railroad.

Each householder procured the necessary domestic water supply from his own well or cistern. For artifical light everybody carried a lantern out of doors and kerosene lamps supplied all buildings. In all kinds of weather, and in all seasons, the inhabitants walked in the common highway; in dust, or mud or snow. Occasionally an unusually industrious inhabitant laid down a stray board, at a particularly muddy place, for his use. The dead were unprofessionally attended by their fellow villagers and were taken elsewhere for burial, in farm wagons, often as far as thirty miles away. The townspeople had to go several miles to vote in elections.

They had a post office, a carpenter shop, a blacksmith shop, a wagon shop a shoemaker's shop, a tinner's shop, a saloon, a doctors office, a general store

The Civil War left Lytle City more than its share of crippled men and intense post-war bitterness of feeling toward "the Southerners". Old soldiers went about in the dingy remnants of old blue army uniforms. Empty sleeves and crutches were common insignia of practical patriotism. Daily there were rehearsals of war tragedies and atrocities in "rebel prisons". The town was steeped in fierce Union sentiment and patriotic prayers for retribution. The "rebellion" was the ever recurring topic of conversation, and the talk was ever abounding in such words as "secessionists", "rebels", "copperheads", "Southerners", "slaveholders", and "traitors".

There was nothing from the outside world but the daily stage from Iowa City or Marengo, the mail, an infrequent traveling salesman, a wayfaring "prairie schooner" on its way west, an occasional visitor to one of the families, or an inhabitant returning from market.

The mail was brought in by "stage" from Iowa City or Marengo. The coach consisted of a three-seated spring wagon with a canvas top, drawn by two horses. It also carried light freight and passengers. A town sensation was the coming of the stage. This was the most available opportunity for actual contacts with the outside world. The stage came from the railroad and the telegraph and brought occasional strangers as well as news.

The country school at the edge of Lytle City was probably a typical "district school" of the time in rural Iowa. The thick brush around it, in the opinion of successive directors, rendered expenditures for the customary outhouses unnecessary. Long benches around the room were the seats for the pupils. One small blackboard was at one end of the room. One stove, which consumed several four-foot sticks of wood at at time and was always red hot, supplied heat in the winter. The pupils burned on one side while they froze on the other. Drinking water for the pupils was carried for the pupils by them in buckets to the school house from a well six hundred feet distant. All the pupils had a perpetual cold and coughed incessantly throughout the winter. When the pupils recited, they stood in a row lengthwise of the room. There were no grades. In arithmetic the pupils worked individually; the teacher going from pupil to pupil at their seats to give needed instruction. They were regularly in various stages of advancement in the different subjects, except reading which was conducted in classes. The pupils ranged in age from six to twenty-one years.

In summer, Indians were a common sight at Lytle City, wandering from their reservation at Tama on long begging trips--braves, squaws, boys, girls, papooses, ponies, bows, and arrows. They shot arrows at targets for pennies, stared into the windows of dwelling houses, scaring women and children and begged articles of food and apparel. The same Indians returned summer after summer.

A papoose had been buried on a farm near Lytle City and Indians visited the grave every summer. The farm was sold, but the new owner could not be induced to take title while the grave was on the land; so the little body was moved to a cemetery in another town. One day the former owner's house was unexpectedly flooded with indignant In-dians, demanding explanations, apologies, sanctions, and reparations. The "grave robber" was suddenly stupefield, but he finally got his wits together and took the rebellious Indians to the cemetery. There he displayed to them the grave of the papoose with its suitable headstone appropriately in-scribed. The Indians walked aside inarticulate for a private conference. In a few minutes they returned, expressed their satisfaction and signified peace. The "grave robber" again breathed freely.

It was a difficult job to bring goods to Lytle City from the nearest railroad point, seventeen miles distant. They were hauled in wagons by horses from South Amana, through dust, mud, hot sun, or rain of summer, and cold or snow of winter. The round trip required a long day of six-teen to eighteen hours in the best of weather.

The country around Lytle City was thickly settled with farmers, who gave the town somewhat voluminous and varied activity. Many of them were Irish immigrants, but there were also English, Germans, and Yankees.

In 1884 the town's death knell was sounded by the coming of the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul Railroad, a few miles to the west, running north and south between Marion and Ottumwa. Nearby, the village of Parnell was established. To the new town the remaining inhabitants of Lytle City promptly moved, taking their very houses with them.

Thus ended Lytle City, after twenty-seven years of wistful, watchful waiting for a railroad, to be succeeded by forty acres of tall corn.