http://www.kanepa.com/folklore%202.htm

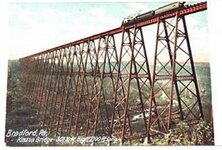

Between forty and fifty thousand dollars in gold and currency is buried in glass jars, within a short distance of what last century’s writers described as "the eighth wonder of the world." Nor were they extravagant in their claims, for on July 5, 1975, the historic Kinzua Viaduct was dedicated as a state park by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Since the value of the lost money was calculated by the standards of the time, it could mean the gold coins could conceivably be worth five times their original value. Believed to be buried a few inches below the ground and covered by a tri-cornered rock, the lost loot is thought to be in the Wildcat Hollow region of Pennsylvania’s McKean County, somewhere between the extinct village of Marvindale and Mt. Jewett. Marvindale, the seat of a chemical factory for almost a century, passed into obscurity a few decades back. Mt. Jewett, a bustling Scandinavian community on Route 6, is noted for its annual Swedish Festival, visited by thousands of tourists from all over America. Kinzua Bridge is but three miles from Mt. Jewett.

The great viaduct soars 301 feet into the air, and stretches across the gorge of the same name. It was completed in just 94 days working time, using only a gin pole to erect the first great steel tower, and then a crane for each of the following nineteen. More than 3,000,000 pounds of wrought iron went into the construction of the bridge, which teetered like a hammock whenever a string of cars passed overhead.

Anthony Bonzano, builder of the bridge, calculated that wind pressure of thirty pounds per square foot would sweep every car from the tracks. So it was ordered that engineers had to proceed at the speed of five miles per hour when crossing the shimmying iron viaduct. Oftentimes gondolas were completely emptied of their cargo of pine bark by the awesome force of the winds, and there are records of box cars having their roof snatched.

The great bridge, the brainchild of General Thomas Kane, railway magnate and founder of the famous Bucktail Regiment of Civil War fame, became one of the greatest tourist attractions of its time, and remains high on the list to this very day. For almost half a century, excursion trains of fourteen cars each, winded their way through Pennsylvania’s mountains to the bridge dedicated by General U. S. Grant, sometimes meeting another dozen trains at the site.

In 1893, about ten miles from the great bridge, was the little town of Palmerville, then a hustling, bustling lumber town. A sawmill, hotels, company store, post office, several stores, a stagecoach stop and perhaps as many as five hundred residents made Palmerville a beehive. The stagecoach often delivered quantities of gold and specie to the company store for meeting payrolls, and in turn postal deposits were shipped by stagecoach.

In the summer of that year, an unknown young man hitched his horse to the rail outside the company store and entered the building. Visiting with the clerk, he pulled a gun at the precise moment that the stage driver entered the store with his bulging leather money bags. Covering the cowering clerk and driver, the lone desperado backed from the store and leaped upon the back of his horse.

Racing like fury westward toward present day Route 6, the lone gunman was seen by farmers in fields. Stopping for a second at the junction of the old dirt Wildcat Hollow Road, the bandit looked in each direction and then headed westward at a furious rate of speed.

For days the woods were combed by volunteers looking for the robber and his loot. Almost a week after the robbery, the searchers came upon a young man who was desperately ill, and wandering through the woods in delirium. Examined by a physician it was determined that the unknown man was critically ill with pneumonia, so he was taken to Smethport, the county seat, where he might be under the care of medical authorities. Upon his recovery he was to be questioned.

For days the bedraggled youth, in his delirium of fever, raved about ". . . the money, the money . . . see the bridge, see the bridge." Then he would lapse into another deep coma.

The young man failed to pass the crisis and expired one morning. Shortly before his death he is alleged to have described a three-cornered rock under which there was money "in glass bottles." Many people felt he was trying to describe the burying place of the stolen loot. Suffice to say, no one has ever reported finding it.

Most contemporaries believe the Kinzua Bridge would have been visible for several miles, 80 years ago, due to the fact that most of the great forests had just been cut away. Only a jungle of stumps and blueberry thickets covered the horizon. Today the great structure is hidden from all, until they are almost on its edge, due to the tremendous second growth timber.

It is believed that in the Wildcat Hollow region, just northeast of the famous bridge, the money is still buried. Hundreds have searched for it, and never found a trace.

However, the affair at Palmerville is well known to the authorities of the McKean County Historical Society, and the curator, Mrs. James McKean, vividly recalls her father’s description of the famous day from her childhood. The Palmerville holdup is often discussed by hunters and fishermen who pass beneath the great arch on an autumn afternoon, and still remains as much of a mystery today as it did then.

Between forty and fifty thousand dollars in gold and currency is buried in glass jars, within a short distance of what last century’s writers described as "the eighth wonder of the world." Nor were they extravagant in their claims, for on July 5, 1975, the historic Kinzua Viaduct was dedicated as a state park by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Since the value of the lost money was calculated by the standards of the time, it could mean the gold coins could conceivably be worth five times their original value. Believed to be buried a few inches below the ground and covered by a tri-cornered rock, the lost loot is thought to be in the Wildcat Hollow region of Pennsylvania’s McKean County, somewhere between the extinct village of Marvindale and Mt. Jewett. Marvindale, the seat of a chemical factory for almost a century, passed into obscurity a few decades back. Mt. Jewett, a bustling Scandinavian community on Route 6, is noted for its annual Swedish Festival, visited by thousands of tourists from all over America. Kinzua Bridge is but three miles from Mt. Jewett.

The great viaduct soars 301 feet into the air, and stretches across the gorge of the same name. It was completed in just 94 days working time, using only a gin pole to erect the first great steel tower, and then a crane for each of the following nineteen. More than 3,000,000 pounds of wrought iron went into the construction of the bridge, which teetered like a hammock whenever a string of cars passed overhead.

Anthony Bonzano, builder of the bridge, calculated that wind pressure of thirty pounds per square foot would sweep every car from the tracks. So it was ordered that engineers had to proceed at the speed of five miles per hour when crossing the shimmying iron viaduct. Oftentimes gondolas were completely emptied of their cargo of pine bark by the awesome force of the winds, and there are records of box cars having their roof snatched.

The great bridge, the brainchild of General Thomas Kane, railway magnate and founder of the famous Bucktail Regiment of Civil War fame, became one of the greatest tourist attractions of its time, and remains high on the list to this very day. For almost half a century, excursion trains of fourteen cars each, winded their way through Pennsylvania’s mountains to the bridge dedicated by General U. S. Grant, sometimes meeting another dozen trains at the site.

In 1893, about ten miles from the great bridge, was the little town of Palmerville, then a hustling, bustling lumber town. A sawmill, hotels, company store, post office, several stores, a stagecoach stop and perhaps as many as five hundred residents made Palmerville a beehive. The stagecoach often delivered quantities of gold and specie to the company store for meeting payrolls, and in turn postal deposits were shipped by stagecoach.

In the summer of that year, an unknown young man hitched his horse to the rail outside the company store and entered the building. Visiting with the clerk, he pulled a gun at the precise moment that the stage driver entered the store with his bulging leather money bags. Covering the cowering clerk and driver, the lone desperado backed from the store and leaped upon the back of his horse.

Racing like fury westward toward present day Route 6, the lone gunman was seen by farmers in fields. Stopping for a second at the junction of the old dirt Wildcat Hollow Road, the bandit looked in each direction and then headed westward at a furious rate of speed.

For days the woods were combed by volunteers looking for the robber and his loot. Almost a week after the robbery, the searchers came upon a young man who was desperately ill, and wandering through the woods in delirium. Examined by a physician it was determined that the unknown man was critically ill with pneumonia, so he was taken to Smethport, the county seat, where he might be under the care of medical authorities. Upon his recovery he was to be questioned.

For days the bedraggled youth, in his delirium of fever, raved about ". . . the money, the money . . . see the bridge, see the bridge." Then he would lapse into another deep coma.

The young man failed to pass the crisis and expired one morning. Shortly before his death he is alleged to have described a three-cornered rock under which there was money "in glass bottles." Many people felt he was trying to describe the burying place of the stolen loot. Suffice to say, no one has ever reported finding it.

Most contemporaries believe the Kinzua Bridge would have been visible for several miles, 80 years ago, due to the fact that most of the great forests had just been cut away. Only a jungle of stumps and blueberry thickets covered the horizon. Today the great structure is hidden from all, until they are almost on its edge, due to the tremendous second growth timber.

It is believed that in the Wildcat Hollow region, just northeast of the famous bridge, the money is still buried. Hundreds have searched for it, and never found a trace.

However, the affair at Palmerville is well known to the authorities of the McKean County Historical Society, and the curator, Mrs. James McKean, vividly recalls her father’s description of the famous day from her childhood. The Palmerville holdup is often discussed by hunters and fishermen who pass beneath the great arch on an autumn afternoon, and still remains as much of a mystery today as it did then.