lookingharder

Sr. Member

- Feb 27, 2015

- 433

- 753

- Detector(s) used

- Whites Coin Master. Garrett AT Gold, Garrett Ace 350

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

This is the story I shared a while back. I lived right behind the Singleton Plantation. We found so many mini balls, we melted them down for sinkers. On two different occasions, I seen someone dig up a full box of musket rifles still wrapped in greased burlap. There's no way this site is hunted out, especially with today's new metal detectors. I would be willing to make a road trip if anyone wanted to go hunt this site. Stay in Sumter which in about a 30 minuet drive to where we park and a two mile walk into the swamp along the rail road track.

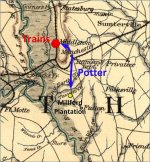

Potter’s Raid, April 20, 1865: “The explosions were terrific” – destruction of trains at Middleton

20 April 2015 Craig Swain American Civil War, Potter's Raid157th New York Infantry, 25th Ohio Infantry, 54th Massachusetts, Camden Branch Railroad, Edmund Clark, Edward Culp, Edward E. Potter, John Laurence Manning, Luis Emilio, Middelton Depot, Millford Plantation, Nathaniel F. Potter, Philip Brown, Singleton Plantation, Susan Hampton Manning

On April 20, 1865, having driven off the last Confederate forces between his forces and the trains on the Camden Branch Railroad the previous day, Brigadier-General Edward Potter sent detachments to Middleton Depot. The destruction of those trains would mark the completion of Potter’s assigned mission – a hard earned completion of the task.

PotterRaidApr20

At least three regiments “worked on the railroad” that morning. Captain Luis Emilio of the 54th Massachusetts recalled:

The rolling-stock was ours, massed on the Camden Branch, whence it could not be taken, as the Fifty-forth had destroyed the trestle at Wateree Junction, on the 11th. General Potter devoted the 20th to its destruction. That day the Fifty-fourth marched to Middleton Depot and with other regiments assisted in the work. About this place for a distance of some two miles were sixteen locomotives and 245 cars containing railway supplies, ordnance, commissary and quartermaster’s stores. They were burned, those holding powder and shells during several hours blowing up with deafening explosions and scattering discharges, until property of immense value and quantity disappeared in smoke and flame. Locomotives were rendered useless before the torch was applied. The Fifty-fourth alone destroyed fifteen locomotives, one passenger, two box and two platform cars with the railway supplies they held.

The 25th Ohio and 157th New York Infantry regiments from First Brigade were also detailed to assist the destruction of the trains. Colonel Philip Brown recorded similar tallies as Emilio’s, indicating some overlap in the accounting by the participants. Major Edward Culp, of the 25th, was closer to the scene:

The next morning, April 20th, the 25th Ohio was sent to the railroad, where for two miles the road was crowded with cars, including sixteen locomotives. The cars were loaded with clothing, ammunition, provisions, and, in fact, everything imaginable. The Regiment was bivouacked some distance from the railroad, and men detailed to fire the train. Several cars were loaded entirely with powder, and in other cars were thousands of loaded shells. The explosions were terrific, and for several hours it seemed as if a battle was being fought. After completely destroying the train the Regiment returned to camp at Singleton’s.

Around noon the work on the trains was nearing completion. Potter’s official report stated the day was spent “thoroughly destroying locomotives, 18 in number, and in burning the cars, of which there were 176.”

While this was going on, Confederate cavalry continued to spar with Potter’s rear guard. Lieutenant Edmund Clark reported, “one howitzer was engaged on the Statesburg road; fired four rounds.” Culp mentioned, “The rebel cavalry still hovered about, and fired into camp continually, but without much damage.” Thus, while no “battle” was taking place, the “fighting” in South Carolina continued, after the “last battle” in South Carolina was over.

Potter’s force returned to the Singleton Plantation, where it had camped from April 12-14. Local residents throughout Sumter County were by that time huddling at various plantations, reeling from over a week of Federal foraging and fighting. To the south of Potter’s camp that evening was Millford Plantation, the home of John Laurence Manning, former state governor. Manning’s wife was Susan Hampton Manning, an aunt of Lieutenant-General Wade Hampton III. Given the connections, one might have expected Millford to become one of many homes in the area to be set afire. But it survived.

The story of how that happened is attributed to different dates, but most often to sometime on April 19 or 20th. The story goes that Potter arrived at Millford and remarked of the beauty of the architecture. Manning responded that the home was designed and built by Nathaniel F. Potter of Rhode Island, adding “and it will be destroyed by a Potter.” With that Potter is said to have responded, “No, you are protected. Nathaniel Potter was my brother.” And thus the Rhode Island granite structure was saved and survives to this day.

A standing representative of the Old South spared to be mixed with the New South as Potter’s raid drew to a close.

Potter’s Raid, April 20, 1865: “The explosions were terrific” – destruction of trains at Middleton

20 April 2015 Craig Swain American Civil War, Potter's Raid157th New York Infantry, 25th Ohio Infantry, 54th Massachusetts, Camden Branch Railroad, Edmund Clark, Edward Culp, Edward E. Potter, John Laurence Manning, Luis Emilio, Middelton Depot, Millford Plantation, Nathaniel F. Potter, Philip Brown, Singleton Plantation, Susan Hampton Manning

On April 20, 1865, having driven off the last Confederate forces between his forces and the trains on the Camden Branch Railroad the previous day, Brigadier-General Edward Potter sent detachments to Middleton Depot. The destruction of those trains would mark the completion of Potter’s assigned mission – a hard earned completion of the task.

PotterRaidApr20

At least three regiments “worked on the railroad” that morning. Captain Luis Emilio of the 54th Massachusetts recalled:

The rolling-stock was ours, massed on the Camden Branch, whence it could not be taken, as the Fifty-forth had destroyed the trestle at Wateree Junction, on the 11th. General Potter devoted the 20th to its destruction. That day the Fifty-fourth marched to Middleton Depot and with other regiments assisted in the work. About this place for a distance of some two miles were sixteen locomotives and 245 cars containing railway supplies, ordnance, commissary and quartermaster’s stores. They were burned, those holding powder and shells during several hours blowing up with deafening explosions and scattering discharges, until property of immense value and quantity disappeared in smoke and flame. Locomotives were rendered useless before the torch was applied. The Fifty-fourth alone destroyed fifteen locomotives, one passenger, two box and two platform cars with the railway supplies they held.

The 25th Ohio and 157th New York Infantry regiments from First Brigade were also detailed to assist the destruction of the trains. Colonel Philip Brown recorded similar tallies as Emilio’s, indicating some overlap in the accounting by the participants. Major Edward Culp, of the 25th, was closer to the scene:

The next morning, April 20th, the 25th Ohio was sent to the railroad, where for two miles the road was crowded with cars, including sixteen locomotives. The cars were loaded with clothing, ammunition, provisions, and, in fact, everything imaginable. The Regiment was bivouacked some distance from the railroad, and men detailed to fire the train. Several cars were loaded entirely with powder, and in other cars were thousands of loaded shells. The explosions were terrific, and for several hours it seemed as if a battle was being fought. After completely destroying the train the Regiment returned to camp at Singleton’s.

Around noon the work on the trains was nearing completion. Potter’s official report stated the day was spent “thoroughly destroying locomotives, 18 in number, and in burning the cars, of which there were 176.”

While this was going on, Confederate cavalry continued to spar with Potter’s rear guard. Lieutenant Edmund Clark reported, “one howitzer was engaged on the Statesburg road; fired four rounds.” Culp mentioned, “The rebel cavalry still hovered about, and fired into camp continually, but without much damage.” Thus, while no “battle” was taking place, the “fighting” in South Carolina continued, after the “last battle” in South Carolina was over.

Potter’s force returned to the Singleton Plantation, where it had camped from April 12-14. Local residents throughout Sumter County were by that time huddling at various plantations, reeling from over a week of Federal foraging and fighting. To the south of Potter’s camp that evening was Millford Plantation, the home of John Laurence Manning, former state governor. Manning’s wife was Susan Hampton Manning, an aunt of Lieutenant-General Wade Hampton III. Given the connections, one might have expected Millford to become one of many homes in the area to be set afire. But it survived.

The story of how that happened is attributed to different dates, but most often to sometime on April 19 or 20th. The story goes that Potter arrived at Millford and remarked of the beauty of the architecture. Manning responded that the home was designed and built by Nathaniel F. Potter of Rhode Island, adding “and it will be destroyed by a Potter.” With that Potter is said to have responded, “No, you are protected. Nathaniel Potter was my brother.” And thus the Rhode Island granite structure was saved and survives to this day.

A standing representative of the Old South spared to be mixed with the New South as Potter’s raid drew to a close.

Upvote

0