Having never seen knappers using such drift punches , it is interesting to see the punches.

Pressure flaking to finish by using a fine point of an antler tine ,or a heavy copper wire embedded in a tine is a common method here in modern fabrication...

I do see other references to the drifts though.

Pardon me if this one has been posted prior.

[1868 - "A mode of flaking by using a punch is mentioned by some travellers. Catlin thus describes the mode adopted by the Apachees in making flint arrow-heads :

"Like most of the tribes west of and in the Rocky Mountains, they manufacture the blades of their spears and points for their arrows of flints, and also of obsidian, which is scattered over those volcanic regions west of the mountains; and, like the other tribes, they guard as a profound secret the mode by which the flints and obsidian are broken into the shapes they require.

"Every tribe has its factory, in which these arrow-heads are made, and in those, only certain adepts are able or allowed to make them, for the use of the tribe. Erratic boulders of flint are collected (and sometimes brought an immense distance), and broken with a sort of sledge-hammer, made of a rounded pebble of horn-stone, set in a twisted withe, holding the stone, and forming a handle."

"The flint, at the indiscriminate blows of the sledge, is broken into a hundred pieces, and such flakes selected as, from the angles of their fracture and thickness, will answer as the basis of an arrow-head."

"The master workman, seated on the ground, lays one of these flakes on the palm of his left hand, holding it firmly down with two or more fingers of the same hand, and with his right hand, between the thumb and two fore-fingers, places his chisel (or punch) on the point that is to be broken off; and a cooperator (a striker) sitting in front of him, with a mallet of very hard wood, strikes the chisel (or punch) on the upper end, flaking the flint off on the under side, below each projecting point that is struck. The flint is then turned and chipped in the same manner from the opposite side, and so turned and chipped until the required shape and dimensions are obtained, all the fractures being made on the palm of the hand."

"In selecting a flake for the arrowhead, a nice judgment must be used, or the attempt will fail: a flake with two opposite parallel, or nearly parallel, planes is found, and of the thickness required for the centre of the arrow-point. The first chipping reaches near to the centre of these planes, but without quite breaking it away, and each chipping is shorter and shorter, until the shape and the edge of the arrow-head are formed."

"The yielding elasticity of the palm of the hand enables the chip to come off without breaking the body of the flint, which would be the case if they were broken on a hard substance. These people have no metallic instruments to work with, and the instrument (punch) which they use, I was told, was a piece of bone ; but on examining it, I found it to be a substance much harder, made of the tooth (incisor) of the sperm-whale, which cetaceans are often stranded on the coast of the Pacific. This punch is about six or seven inches in length, and one inch in diameter, with one rounded side and two plane sides ; therefore presenting one acute and two obtuse angles, to suit the points to be broken.

This operation is very curious, both the holder and the striker singing, and the strokes of the mallet given exactly in time with the music, and with a sharp and rebounding blow, in which, the Indians tell us, is the great medicine (or mystery) of the operation." (Last Rambles among the Indians, Catlin).]

Revelantchair,

It is not by accident that you have not seen knappers using antler drifts.

Between the 1960's and the 1970's modern knappers thought that they had "debunked" the proposed use of antler cylinders in indirect percussion styled flintknapping.

During the 1980's, and 1990's, the subject appears to have been more or less forgotten by modern flintknappers. During that time, "billet styled" knapping became very popular. But, by the 1980's, many archaeologists were noticing the lack of billets in archaeological sites, as culturally predictable traits.

In other words, archaeologists finally began to see that the predictable manufacture, use, and final disposal, of antler billets could not be documented as a cultural trait pertaining to any culture. Flintknappers wrote this off by saying things like, "The soil acids ate all of the billets".

But, if an honest person went through fifty years worth of site reports, he would have to admit that archaeologists have been digging up antler artifacts in all of these sites, going back to the turn of the 20th century, and in some cases, even earlier.

But, something else happened within the flintknapping community, that threw a wrench in the works. The best flintknappers ended up using copper percussion, and not antler percussion. These were people who were true forgers. These were people who were making big bucks off of flintknapping. As one late world class knapper told me, they just could not get the right flake scars with antler percussion. But, they could with copper percussion.

So, if we see the flintkapping community as having both "black hat" knappers, and "white hat" knappers, the black hat knappers proved that antler billet flaking was inferior to methods that could not possibly have been used, since the advent of the Ice Age. In other words, one wing of the flintknapping community, to some degree, undermined the claims made by the other wing, at least in the minds of honest people. Also, the "white hat" knappers were used to using heavy moose and elk club billets - something that is hardly a culturally predictable trait, anywhere.

So, what happened to the original evidence? It was conveniently being overlooked by people who did not have the means to explain it.

Between 2005 and 2010, I frequented flintknapping forums, more out of my interest in ancient knapping, then anything else. And, between looking at what modern knappers were doing, and what I saw in artifacts, I arrived at the conclusion that what is seen in artifacts cannot always be explained by billet knapping. For example, who could a flute be removed from inside an indentation, when the percussor cannot fit inside the indentation, or the base, of an artifact? Back in the 1930's archaeologists looked at Folsom points, and wondered the very same thing. And, they concluded - as I concluded - that maybe indirect percussion was involved, at least in removing a channel flake.

So, before 2010, I found myself suspecting that something else was going on, in some instances. But, what I did not know. And, when I wrote to modern replicators like Bob Patten, I was not satisfied by some of the answers...

Then, in 2010, I found out about an obscure Lacandon blade core technology that I had never heard about, before. So, I set out to find further information, which was very hard to come by.

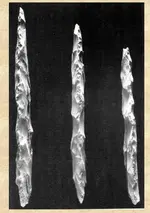

Surprisingly, this quest for information led me to stumble upon a class of artifacts, known from North America, as "antler drift". This term, I believe, was coined around 1940 by Webb. But, the actual tools were described under various names going back to, possibly, the 1880's or 1890's, which early references pertaining to the Madisonville cemetery site, in Ohio.

Now, here is what I can say, from 2005 until 2010, I never heard one knapper bring up the subject of antler drift on any flintknapping site, forum, or thread. But, I found them in archaeological reports, from every decade, spanning from around 1900 all the way through the 1970's. And, what became clear is that the more archaeologists actually dug sites, the more they found these tools, and wrote about them. And, later archaeologists who do not do so much digging, and much more theorizing, seemed to know less about them. In other words, archaeologists did not know about the tool on account of any theory. They knew about the tool because they found it over and over again.

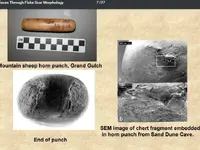

In fact, a greater presence of such tools was correlated with a greater presence of chipped stone industry. A lack of such tools was negatively correlated with a lack of chipped stone tool production. The tools were frequently found in prehistoric workshops. By the 1960's the presence of an antler drift in a grave was recognized as a predictable sign that the burial was that of a prehistoric flintknapper. Some researchers noticed the cellular compaction of cells from pounding. Still, other researchers noted the signs of silicate materials being embedded in the ends. The list of observations made by many independent researchers, spans for over a half a century.

But, modern flintknappers said that the tools were of no use. And, it was really a handful of modern knappers who used to hold a great deal of sway, before the advent of the internet. So, we basically were stuck with the opinions of a relatively small cabal of both white hat, and black hat knappers.

Anyway, between 2005 and 2010, I was well liked on various flintknapping forums. I was given gifts, and invited to go to knapins. Better knappers were kind enough to share their pointers with me, etc.

Also, during that time, I had a very overly-generalized view about prehistoric flintknapping. I envisioned the opposite of what actually had taken place. I thought that knappers figured out how to make up special technologies "on the fly", McGyver style.

But, in 2010, I saw a discrepancy between all of these generalized ideas about knapping, and the issue of "antler drift". or "antler cylinders". So, I carefully started going through dozens - maybe hundreds - of archaeological reports. And, the more I looked, the more evidence I found. Only, it was nothing that I had ever heard flintknappers speak about.

So, finally, one day in 2010, I wrote the following words on the Paleoplanet flintknapping forum: "It seems to me that Native American knappers had been using some sort of indirect percussion that has never been understood."

This statement was immediately rebuffed by a nationally known replicator, and author, named Bob Patten. He responded by saying that "there is no evidence", and the idea is a "pipedream", and indirect percussion was only used in blade core work, but not bifacial reduction.

Well, to the charge of "no evidence", I new that he was wrong. But, his pronouncements were followed by a sort of "public pile on", with flintkappers demanding to see such evidence.

So, I started posting archaeological evidence, as I have done here . This eventually led to a division between factions of flintknappers. Some refused to address or acknowledge the evidence that was posted, while others demanded that I "prove it".

Now, to the latter charge, they were demanding something that not even Don Crabtree had been able to do, and that they had not been able to do.

So, I began to carry out experiments, and post the results, which were mostly ridiculed or disparaged. But, I saw that the "black hat" and "white hat" flintknappers were actually quite divided. And, so I realized that even though one faction wanted the subject dismissed, the other faction wanted to contest everything that was said or shown.

I also saw that their weakness was that no one could give an honest accounting for why they were not doing better with antler billet flaking. It was something that no one wanted to talk about, while almost all of them quietly jumped ship, for copper percussion. And, I reasoned that they had to have more honest people in the mix, especially new people.

So, while I saw that the archaeological data was never going to get a fair trial, I realized that I would be able to get the data out there by driving a permanent wedge into the flintknapping community, until the people could never reunite, as they had previously done under a small "cabal" of nationally known leaders.

So, after six months of patiently showing evidence from archaeology, I changed tactics and began to vigorously respond to everyone who contested the evidence.