Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,474

- 3,795

BLESSED are the myth makers; for theirs is the kingdom of the nonexistent. And unto us, who are not of the elect, is given the blessed privilege of belief; and belief in the four cardinal myths is the Archimedean lever that has moved the world ever since prehistoric man began to walk erect. To hitch our wagon to a star, to build airy castles in Spain, ever to pursue the unattainable, --- these are not the idle and unprofitable pastimes of the weak and foolish, but the inspired employments of those who have imbibed most deeply of the wisdom of the ages. For the dreamer of one age is the prophet of the next; and imagination has revealed more truths than the explorers of science ever suspected.

The myths of friendship, of true love, of fame, and of hidden fortune, --- these have been the real mainsprings of human action ever since some hairy troglodyte first forsook the ready bone for the secret cache of his provident neighbor, or forgot the ungainly lady that shared his humble cave to bask in the smiles of some siren affinity from afar. Thus were born the myths of hidden treasure and of true love; and doubtless the genesis of the myths of fame and friendship was equally obscure. That all are only myths each one has proved --- or must some day prove --- from dear experience. But what of that? Being myths, they are ubiquitous and immortal, unhampered by the limitations of time, place, and circumstance that circumscribe the influence of uncompromising facts.

Which of these four primal and eternal myths --- fame, friendship, love, or buried treasure --- has contributed most liberally to the sum total of human achievement, it would be vain to speculate. Had any been eliminated from the divine plan, the world would now present a very different aspect: the art, science, politics, religion, and all the amenities that make life tolerable would be nonexistent. Had all been omitted, any approximation to civilization would be unthinkable, and mankind could never have become wholly differentiated from the ancestral beast.

Nevertheless, it can hardly be questioned that the treasure myth has always appealed to the greatest number. There are millions who have been awakened from dreams of undying love by the discovery that their idols had feet of very common clay; and millions more who have found that the fondest friends are the first to betray. Those who have plucked its richest pronounce them but Dead Sea apples, turning into dust and ashes, which satisfy not. But when love is dead, friendship forsworn, and fame despised, avarice still survives; and the heart that recognizes no other passion still throbs the faster at a tale of lost or hidden or stolen treasure: the hoard of some self starved miser, the cask of a Captain Kidd, the golden cargo of a sunken galleon, a lost mine, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Everywhere, under an infinity of guises it is true, but always appealing to man's master passion, greed, the treasure myth has lured men on to fresh adventures, to epochal discoveries, to daring explorations, to wild hazards of life and honor and fortune. Never yet, perhaps, have the chasers of treasure myths found what they sought; but their self seeking has built well for those who came after.

Myth of the Quivira

TWO of the most remarkable chapters in the history of American exploration deal solely with the chase of the treasure myth. In South America it was the myth of the Dorado ---the Gilded Man --- that inspired the Conquistadores to perform deeds of almost unbelievable valor. That particular version of the treasure myth had a real foundation in fact; but long after El Dorado had disappeared forever beneath the waters of Lake Guatavita the search for him still continued.

In the north, it was the myth of the Quivira that led to the first great interior exploration of territory now comprised in the United States, sixty-seven years before Jamestown was founded. It inspired perhaps the most amazing land journey of exploration ever performed, and played a part of the first importance in the settlement and colonization of the vast territory of the Southwest, --- from the Missouri River to the coast of California. It never had a grain of fact for its foundation; but it has been paid a tribute of blood nearly every year for three hundred and sixty-eight years, and is implicitly believed to this day by hundreds of deluded victims, some of whom are doubtless wasting their energies on the burning sands of the New Mexican desert, delving for treasures that never existed, at the very moment these lines are meeting the eye of the reader.

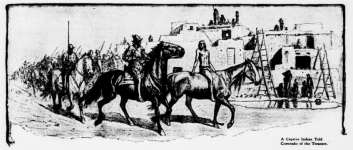

The Quivira myth was born at the Pueblo of Pecos, in Northern New Mexico, in 1540. Coronado had penetrated that far into the inhospitable wilderness, in the hope of finding another Mexico. It is not probable that he would have gone farther, had not a captive plains Indian assured him that the Quiviras, living far to the northeast, possessed an inexhaustible treasure of the yellow metal that the Spaniards sought. No doubt the lie was manufactured by the Pecos Indians, who compelled the captive to tell it to the credulous Spaniards in order to rid themselves of unwelcome guests. The bait was taken, and Coronado and his men started forth on their rainbow chase, with their informant (called the Turk) as guide.

For nearly a thousand miles that little band of treasure seekers traversed desert and plain, until at last the country of the Quiviras was reached somewhere near the present site of Kansas City. Imagine their disappointment at finding only a horde of naked nomads, ignorant of what gold looked like, and possessing no "treasure" with the exception of a little disk of copper, worn proudly by the savage chief. So far as Coronado was concerned, the Quivira myth was exploded forever. So he savagely cut off the head of the perfidious Turk, and retraced his steps back to Mexico, pronouncing the whole country to the north to be barren, sterile, and worthless.

THAT ought to have killed the fable of the wealth of the Quiviras for all time; but in a little while it bobbed up serenely, with more vitality than ever. Had not Coronado gone in search of the treasures of the Quiviras, and tailed to find them? Then of course they must still exist to reward some more lucky searcher. Among the great names enrolled on the list of the wooers of this siren of the Southwest, who have left a record of their fruitless wanderings, are those of Juan de Onate, Alonzo Vaca, Governor Luis de Rosas, Diego de Guadalajara, and Juan Dominguez de Mendoza, while thousands of others kept up an unremitting chase of the will-o’-the-wisp for three hundred years.

After the unlucky Turk lost his head, the Quivira myth became a wanderer, with none to fix its habitation. Within comparatively recent years, it has become localized at a spectral gray ruin, eighty miles southeast of Albuquerque, on the saline plains east of the Manzano Mountains, known throughout New Mexico as Gran Quivira. In reality the ruin is the crumbling remnant of the Pueblo Indian town of Tabira, with its great stone church founded by the Franciscan fathers some two and a half centuries ago, and destroyed by the Comanche Indians about 1677. How it happened that Tabira was confused with Quivira, some long dead romancer of the mining camps might be able to explain, could one interview him in the land of shades; but no living being now knows.

In any event, this spectral quadrangle fronting the dark Mesa de los Jumanos is a fit home of romance. The ruins must be counted among the most imposing in America; while the vast solitudes, rimmed by purple mountain peaks, unbalance the mind of the coolest to such an extent that he is willing to believe anything. It doesn't seem strange, therefore, that men have drilled for a hundred feet or more into solid bedrock in search of "buried" treasure; and that the fortune hunters have tunneled the fallen church and convent, the crumbling piles of the communal houses of the Indians, the half-subterranean estufas in which the forgotten priests of the pagan red men used to perform oblations to strange gods, in search of imaginary gold. Nor is it at all likely that the myth of Gran Quivira (whence came the "Gran" is another mystery) will be fully laid for centuries yet to come.

Mysteries of Tabira

IT is probable that the aboriginal population of Tabira numbered at least fifteen hundred. Yet this sepulchral ruin is more than thirty miles from water, at an elevation of six thousand and forty-seven feet. It is this fact that has brought death to many and suffering to all those who have delved for the treasures of Gran Quivira. Round about are a million acres of pasture land, on which not a hoof nor a horn can be seen, because of the dearth of water there.

Hence, for many years the Territory of New Mexico has offered a reward of ten thousand dollars to anyone who would discover the lost water of Gran Quivira. Perhaps the lost water is as mythical as the lost treasure; for the Indians who dwelt there were true children of the desert, and vast ruined reservoirs are still distinguishable. It may be that they depended for their supply upon water

caught and stored on the occasion of the infrequent rains. Others conjecture that the springs that supplied Tabira were destroyed by an earthquake shock; and the few that dig for water instead of for gold believe they were cunningly choked up and hidden by the destroyers of the community, to prevent it from ever again being occupied.

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

The myths of friendship, of true love, of fame, and of hidden fortune, --- these have been the real mainsprings of human action ever since some hairy troglodyte first forsook the ready bone for the secret cache of his provident neighbor, or forgot the ungainly lady that shared his humble cave to bask in the smiles of some siren affinity from afar. Thus were born the myths of hidden treasure and of true love; and doubtless the genesis of the myths of fame and friendship was equally obscure. That all are only myths each one has proved --- or must some day prove --- from dear experience. But what of that? Being myths, they are ubiquitous and immortal, unhampered by the limitations of time, place, and circumstance that circumscribe the influence of uncompromising facts.

Which of these four primal and eternal myths --- fame, friendship, love, or buried treasure --- has contributed most liberally to the sum total of human achievement, it would be vain to speculate. Had any been eliminated from the divine plan, the world would now present a very different aspect: the art, science, politics, religion, and all the amenities that make life tolerable would be nonexistent. Had all been omitted, any approximation to civilization would be unthinkable, and mankind could never have become wholly differentiated from the ancestral beast.

Nevertheless, it can hardly be questioned that the treasure myth has always appealed to the greatest number. There are millions who have been awakened from dreams of undying love by the discovery that their idols had feet of very common clay; and millions more who have found that the fondest friends are the first to betray. Those who have plucked its richest pronounce them but Dead Sea apples, turning into dust and ashes, which satisfy not. But when love is dead, friendship forsworn, and fame despised, avarice still survives; and the heart that recognizes no other passion still throbs the faster at a tale of lost or hidden or stolen treasure: the hoard of some self starved miser, the cask of a Captain Kidd, the golden cargo of a sunken galleon, a lost mine, the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Everywhere, under an infinity of guises it is true, but always appealing to man's master passion, greed, the treasure myth has lured men on to fresh adventures, to epochal discoveries, to daring explorations, to wild hazards of life and honor and fortune. Never yet, perhaps, have the chasers of treasure myths found what they sought; but their self seeking has built well for those who came after.

Myth of the Quivira

TWO of the most remarkable chapters in the history of American exploration deal solely with the chase of the treasure myth. In South America it was the myth of the Dorado ---the Gilded Man --- that inspired the Conquistadores to perform deeds of almost unbelievable valor. That particular version of the treasure myth had a real foundation in fact; but long after El Dorado had disappeared forever beneath the waters of Lake Guatavita the search for him still continued.

In the north, it was the myth of the Quivira that led to the first great interior exploration of territory now comprised in the United States, sixty-seven years before Jamestown was founded. It inspired perhaps the most amazing land journey of exploration ever performed, and played a part of the first importance in the settlement and colonization of the vast territory of the Southwest, --- from the Missouri River to the coast of California. It never had a grain of fact for its foundation; but it has been paid a tribute of blood nearly every year for three hundred and sixty-eight years, and is implicitly believed to this day by hundreds of deluded victims, some of whom are doubtless wasting their energies on the burning sands of the New Mexican desert, delving for treasures that never existed, at the very moment these lines are meeting the eye of the reader.

The Quivira myth was born at the Pueblo of Pecos, in Northern New Mexico, in 1540. Coronado had penetrated that far into the inhospitable wilderness, in the hope of finding another Mexico. It is not probable that he would have gone farther, had not a captive plains Indian assured him that the Quiviras, living far to the northeast, possessed an inexhaustible treasure of the yellow metal that the Spaniards sought. No doubt the lie was manufactured by the Pecos Indians, who compelled the captive to tell it to the credulous Spaniards in order to rid themselves of unwelcome guests. The bait was taken, and Coronado and his men started forth on their rainbow chase, with their informant (called the Turk) as guide.

For nearly a thousand miles that little band of treasure seekers traversed desert and plain, until at last the country of the Quiviras was reached somewhere near the present site of Kansas City. Imagine their disappointment at finding only a horde of naked nomads, ignorant of what gold looked like, and possessing no "treasure" with the exception of a little disk of copper, worn proudly by the savage chief. So far as Coronado was concerned, the Quivira myth was exploded forever. So he savagely cut off the head of the perfidious Turk, and retraced his steps back to Mexico, pronouncing the whole country to the north to be barren, sterile, and worthless.

Others Came After

THAT ought to have killed the fable of the wealth of the Quiviras for all time; but in a little while it bobbed up serenely, with more vitality than ever. Had not Coronado gone in search of the treasures of the Quiviras, and tailed to find them? Then of course they must still exist to reward some more lucky searcher. Among the great names enrolled on the list of the wooers of this siren of the Southwest, who have left a record of their fruitless wanderings, are those of Juan de Onate, Alonzo Vaca, Governor Luis de Rosas, Diego de Guadalajara, and Juan Dominguez de Mendoza, while thousands of others kept up an unremitting chase of the will-o’-the-wisp for three hundred years.

After the unlucky Turk lost his head, the Quivira myth became a wanderer, with none to fix its habitation. Within comparatively recent years, it has become localized at a spectral gray ruin, eighty miles southeast of Albuquerque, on the saline plains east of the Manzano Mountains, known throughout New Mexico as Gran Quivira. In reality the ruin is the crumbling remnant of the Pueblo Indian town of Tabira, with its great stone church founded by the Franciscan fathers some two and a half centuries ago, and destroyed by the Comanche Indians about 1677. How it happened that Tabira was confused with Quivira, some long dead romancer of the mining camps might be able to explain, could one interview him in the land of shades; but no living being now knows.

In any event, this spectral quadrangle fronting the dark Mesa de los Jumanos is a fit home of romance. The ruins must be counted among the most imposing in America; while the vast solitudes, rimmed by purple mountain peaks, unbalance the mind of the coolest to such an extent that he is willing to believe anything. It doesn't seem strange, therefore, that men have drilled for a hundred feet or more into solid bedrock in search of "buried" treasure; and that the fortune hunters have tunneled the fallen church and convent, the crumbling piles of the communal houses of the Indians, the half-subterranean estufas in which the forgotten priests of the pagan red men used to perform oblations to strange gods, in search of imaginary gold. Nor is it at all likely that the myth of Gran Quivira (whence came the "Gran" is another mystery) will be fully laid for centuries yet to come.

Mysteries of Tabira

IT is probable that the aboriginal population of Tabira numbered at least fifteen hundred. Yet this sepulchral ruin is more than thirty miles from water, at an elevation of six thousand and forty-seven feet. It is this fact that has brought death to many and suffering to all those who have delved for the treasures of Gran Quivira. Round about are a million acres of pasture land, on which not a hoof nor a horn can be seen, because of the dearth of water there.

Hence, for many years the Territory of New Mexico has offered a reward of ten thousand dollars to anyone who would discover the lost water of Gran Quivira. Perhaps the lost water is as mythical as the lost treasure; for the Indians who dwelt there were true children of the desert, and vast ruined reservoirs are still distinguishable. It may be that they depended for their supply upon water

caught and stored on the occasion of the infrequent rains. Others conjecture that the springs that supplied Tabira were destroyed by an earthquake shock; and the few that dig for water instead of for gold believe they were cunningly choked up and hidden by the destroyers of the community, to prevent it from ever again being occupied.

----- END of PART I - To Be Continued -----

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo