Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,474

- 3,797

The Lost Mines of the Desert - Part IX:

LOST MINE of ARIZONA.

from The Miner’s Guide; A Ready Handbook for the Prospector and Miner, by Horace J. West (Los Angeles: Second Edition — 1925)

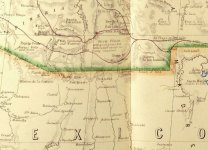

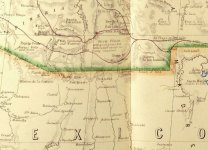

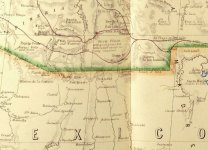

Note where the green border between the US and Old Mexico comes from the northwest and turns straight east

In the last century, one of the most notable mines of what is now Arizona was the one called the Planchas de Plata, the “planks of silver.” Its exact location is unknown now, though the neighborhood in which it was found is plainly indicated by the old records and letters. Don Manual Retes, in 1861 Capitan of the port of Mazatlan, thus spoke of this mine, in an essay on the mineral resources of Northern Sonora:

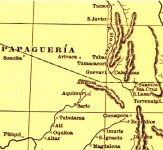

“This mineral deposit, situated 31 1/2° north, long. 111 1/2° west of Greenwich, is described by the Jesuits as having been discovered by a Yaqui Indian, towards the commencement of the last century [1800s], distant from four to five leagues from the line of Arizona; about fifteen from the town of Tumacaicori, the nearest settlement; about twenty-five from the Presidio of Santa Cruz; nearly ninety from Ures, and about one hundred and thirty from Guaymas. The silver was discovered in sheets of different size, from which the name of Planchas de Plata, ‘sheets of silver,’ originated. They were found almost on the surface, perfectly pure, and without adhering to any foreign substance; in a flexible state, capable of receiving impressions, and only hardening on being exposed to the atmosphere. The region which produces the same is an earth of the color of, and very similar to, ashes, which extends in visible leads more or less wide, and in parts subdivided in veins, over all the hills and mountains adjoining the main deposit. Among the sheets extracted, two are worth mentioning — especially one which on account of its almost fabulous size, weighing one hundred and forty-nine arrobas[SUP]1[/SUP], it was found necessary to employ the heat of four forges at the same time to reduce to a smaller bulk — the other weighed twenty-one arrobas, though according to other accounts it was much larger. The news of such immense lumps having been found, without the investment of much labor, could not fail to convey a great number of people to that region, not only from the neighboring settlements, but also from the most distance provinces. The amount of silver extracted within a very short period, amounted to 400 arrobas, or five tons.”

Another mine very rich in silver was the Arizona; the position of which is also lost. It was in search of this mine that Count Raousset de Boulbon [the “Little Wolf” — Baily] made his celebrated expedition into Sonora, whither he went, at first, in good faith and with peaceable intentions, though after he had been defrauded and attacked, he turned filibuster. There are persons who are ready to assert that the exact position of the Arizona mine is known; but the best informed say it is not.

--- o0o ---

When I started on these Notes I thought they would be easy. After all, this is the shortest story in the Lost Mines of the Desert West saga. It turned out to be the most complicated. This, of course, is the reason we actually do the research. You can’t know the whole story until you really look into it.

Almost all versions of this legend point out the combination of a remarkably hostile part of the world and very hostile native residents (Apache, Papago and Pima) made the Planchas de Plata very difficult to develop, once the prospect had been located. The dangers of the desert remain, so this is an excellent opportunity to again quote these words of wisdom from the old prospector Philip Baily:

To begin with, sadly, it must be acknowledged that West’s account was taken, word-for-word, from John S. Hittell’s Mining in the Pacific States of North America (San Francisco: 1861). So many authors helped themselves to West’s work it almost seems fair he did the same thing — although I will not defend such blatant plagiarism.

Now — what makes these seemingly simple tales so complex? There is the story of the name “Arizona.” And there is the question: are these two different prospects?

The Arizona was a legendary lost mine and the Planchas or Bolas de Plata a verified, if short-lived, silver placer if not actually a mine. But was the Planks, or Balls, of Silver located in the Arizona cañyon?

An absolutely essential work on the topic is the first-rate article by Adlai Feather (of Messila Park, New Mexico) — “Origin of the Name Arizona.” It appeared in the New Mexico Historical Review, April 1964 (Vol. XXXIX — No. 2). It is a masterful summary of the history of the Arizona “mine” which produced some 10,000 pounds of native silver, and of the origins of the Arizona name. It also briefly tells the story of Hugh Stephenson of El Paso, who financed a search in the Organ Mountains for the “Padre Mine.” His exploration party didn’t find it — but they did locate and he then developed a lode that turned out to be a million dollar silver mine! This is not the only time a hunt for fabled wealth has produced such unexpected — although quite happy - results.

Lost mine hunters will be interested in Feather’s page 99 footnote on the Padre Mine. “In 1879, a Lincoln County merchant named LaRue did a little exploration work at the site” of Frank Flecher’s claim in the San Andres Mountains, three miles north of the San Agustin Pass. Near a stone cabin a shallow cut and a shallow shaft just ten feet deep had been made. “Out of this jumble of indefinite information,” Feather continues, “emerged the legend of ‘The lost mine of Father LaRue.’”

Feather draws extensively on the 1850 work of Francisco Velasco. His book was translated by Wm. F. Nye and published as Sonora: Its Extent, Population, Natural Productions, Indian Tribes, Mines, Mineral Lands, Etc., Etc. (San Francisco: 1861). Apparently the appearance of this information in English led to a silver rush in the region.

Probert apparently considers the Mina de Planchas or Bolas de Plata (Feather, referenced above, states it was also known as the Minas de Bolas) to be the same — and he offers over three pages of sources. His “Anon., ‘Planks of Silver,’ Hand Book of Mining (publisher unknown), San Francisco, 1861, pg. 233” appears to be Hittell, cited above. The “Page 233” is probably a typo — the accounts are on pages 223 and 224.

It comes as no surprise that Ed Bartholomew (“Jesse Ed Rascoe”) discussed this famous find (“Old Spanish Mine Archives”) in The Golden Crescent; The Southwest Treasure Belt (Toyahvale, Texas: 1962). It is instructive that he used R.J. Hinton’s The Handbook to Arizona (1878) as a primary source. Hinton, in turn, quoted Howe, “a recognized authority and megallurgist.” I have not been able to locate which of Howe’s works Mr. Hinton quoted. Perhaps a more able researcher can shed light on that question. “Rascoe” also quotes H.G. Ward [Mexico in 1827] (1828) and Judge Wilson (1855-56).

Back to the story, however. There is an essential thread to this legend — and a useful primer in how lost mine yarns grow and flourish. Because when one digs deeper into the tale, the layers become more discernible.

Herbert Howe Bancroft discusses these mines in both the History of Arizona and New Mexico 1530-1888 (The Works of Herbert Howe Bancroft, Vol. XVII) (San Francisco: 1889) and his History of North Mexican States and Texas, Vol. I (San Francisco: 1884). As usual, he draws upon rare original Spanish documents and must at least be consulted.

Sylvester Mowry’s Arizona and Sonora; The Geography, History, and Resources of the Silver Region of North America (Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged) (New York: 1864) also quotes Ward on the bolas de plata as well as the Criaderos de Plata. He also states:

The name ARIZONA is undoubtly derived from the Aztec. In the original it was Arizuma, and the change is a corruption into the present word, which is accepted as Spanish. We have no decided information as to its meaning, but the impression among those who have been curious enough to investigate is, that it signifies “silver-bearing.” This impression gains strength from the fact that the Arizona mountains are very rich in silver, and that a tradition of a silver mine, called La Arizona, of incredible richness, still exists among the Mexican people near the frontier of our newly-acquired Territory.

Despite the assured presentation, it appears Lieut. Mowry was badly mistaken about the name (although not about the tradition of the rich La Arizona silver mine). The title of the essay by Donald T. Garate, Tumacácori's historian, Arizona (Never Arizonac) neatly sums up his contention — buttressed by considerable documentation. I recommend it.

Although Arizonac (the good oak trees), like Arizona (the good oak tree) is a perfectly viable Basque word, it was never used by the early settlers, soldiers, priests, and miners who lived there. The use of Arizonac is a twentieth century fable that needs to be corrected.

http://www.nps.gov/tuma/historyculture/upload/Arizonac Article.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2013.)

"Toward the end of last October, between the Guevayi Mission and the ranchería called Arizona, some balls and slabs of silver were discovered, one of which weighed more than one hundred arrobas (2,500 pounds), a sample of which I am sending to you, Most Illustrious Lord."

- Captain Juan Bautista de Anza to Bishop Benito Crespo, January 7, 1737.

http://www.nps.gov/tuma/historyculture/arizona-planchas-de-plata.htm

The classic Fantasies of Gold; Legends of Treasure and How They Grew by E.B. “Ted” Sayles (Tucson, Arizona: 1968) offers:

The earliest mining in the Southwest was in the 1700’s. The Spanish king had given mining grants to a select few who worked the rich surface, or shallow, silver deposits such as those west of Nogales, Arizona — only forty miles from Fort Huachuca [site of the “Sergeant Jones’ Treasure”].

These mines were known as the Planchas de Plata (planks of silver). The rich ore was carried south on the backs of burros to a refinery in Mexico or to some shipping place to be sent to Spain. In 1774, gold placers were worked at Quijotoa, north of Sells, Arizona, on the Papago Indian Reservation.

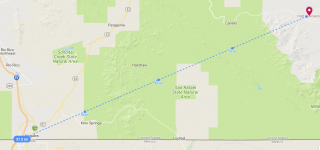

The essential Golden Mirages; The Story of the Lost Pegleg Mine, The Legendary Three Gold Buttes, and Yarns of and by Those Who Know the Desert by Philip A. Baily (New York: 1940) contends the Arizona, found near the Sierra del Pararito, just below the border and about fifteen kilometers southwest of Nogales, was also known as Las Bolas de Plata. This book covers several 19[SUP]th[/SUP] Century searches for this mina perdida — accounts not readily available elsewhere. Baily wrote a detailed account of the Planchas de Plata, pointing out it is both a lost and an “unlost” mine.

Indeed, stories of lost mines being found appear second in number only to accounts of mines being lost in the first place.

Long-time prospector and newspaper man (editor of the Tombstone Epitaph) Wayne Winters wrote “I Found the Planchas de Plata,” published in True West (May-June 1964 — Vol. 11, No. 5). This article does not appear to have been reprinted in GOLD! The mine is also discussed in Mr. Winters’ Campfires Along the Treasure Trail (Tombstone, Arizona: 1963).

The Lost Planchas de Plata Ledge is included in Robert G. Ferguson’s Campfire Tales of Lost Mines and Hidden Treasure (Privately Printed; Tucson, Arizona: 1937). I will let his version represent the countless accounts in lost mine books that can only be relied upon to offer re-worked tales with little novelty and even less accuracy taken from previous writers. It was presented in an issue of GOLD! (Summer 1971 — Vol. 3, No. 3. Ferguson’s pamphlet was enlarged and published as Lost Treasure; The Search for Hidden Gold by the vanity Vantage Press (New York: 1957). Some years later the unbound signatures were located and issued with card covers as a “paperback.” Because at that time the most expensive part of the printing process was the hardcover binding — after the first copy the expenses are only paper and press time — it was typical to bind only a small portion of the printed pages. The author was paying for the work. If demand was there, more copies could always be bound in hardcovers. Apparently it wasn’t. The Ward Ritchie Press (Los Angeles: 1973) reprinted it again as Guidebook to Lost Western Treasure; The Search for Hidden Gold. Now, because the copyright has expired (or, at least, that is the perception) there are modern reprints readily available.

Finally, Charles Rene Gaston Gustave de Raousset-Boulbon is mentioned in passing, above, in the excellent Golden Mirages. This French nobleman, gold prospector, filibuster and adventurer deserves considerably more attention than we can provide here. From his birth in Avignon to his death in the dust of Guaymas, Old Mexico, just thirty-seven years later, executed by firing squad (he distained the traditional blindfold), Count Raousset-Boulbon’s life was the stuff of legend.

My initial draft of these notes included “I sincerely hope someone will bring the extraordinary saga of this soldier of fortune to life — that’s a book I would very much like to read!” Rereading them, Baily’s “Little Wolf” rang a bell in my distant memory. I looked — and I have a copy of The Wolf Cub; The Great Adventures of Count Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon in California and Sonora 1850-1854 [translated from the French of Maurice Soulie] by Farrell Symonds (1927). Now I am very much looking forward to reading it!

This is Part IX and the final episode in the Lost Mines of the Desert West series, posted after another too-lengthy sabbatical. Part I — The Introduction - was posted December 26, 2008. Part II — “The Lost Arch” Diggings went up January 3, 2009. Part III — The Peg-Leg Mine; Or, the God of Fury’s Black Gold Nuggets, was made available January 11, 2009, and may be found under the Lost Peg Leg Mine topic. Part IV — The Lost Papuan Diggings — again saw the light of day on January 19, 2009. Part V — The Lost Dutch-Oven Mine — was posted January 27, 2009. Part VI — The Lost Breyfoggle [sic] appeared February 8, 2009. After a long hiatus Part VII — The Goler Placer Diggings — came out on April 26, 2011. Part VIII — The Lost Gun-Sight Mine — was posted on May 6, 2011. The only lost mine yarn told by Mr. West that has not been presented here is The Lost Tub Placer. That one this editor is saving for a book collection.

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

LOST MINE of ARIZONA.

from The Miner’s Guide; A Ready Handbook for the Prospector and Miner, by Horace J. West (Los Angeles: Second Edition — 1925)

Note where the green border between the US and Old Mexico comes from the northwest and turns straight east

In the last century, one of the most notable mines of what is now Arizona was the one called the Planchas de Plata, the “planks of silver.” Its exact location is unknown now, though the neighborhood in which it was found is plainly indicated by the old records and letters. Don Manual Retes, in 1861 Capitan of the port of Mazatlan, thus spoke of this mine, in an essay on the mineral resources of Northern Sonora:

“This mineral deposit, situated 31 1/2° north, long. 111 1/2° west of Greenwich, is described by the Jesuits as having been discovered by a Yaqui Indian, towards the commencement of the last century [1800s], distant from four to five leagues from the line of Arizona; about fifteen from the town of Tumacaicori, the nearest settlement; about twenty-five from the Presidio of Santa Cruz; nearly ninety from Ures, and about one hundred and thirty from Guaymas. The silver was discovered in sheets of different size, from which the name of Planchas de Plata, ‘sheets of silver,’ originated. They were found almost on the surface, perfectly pure, and without adhering to any foreign substance; in a flexible state, capable of receiving impressions, and only hardening on being exposed to the atmosphere. The region which produces the same is an earth of the color of, and very similar to, ashes, which extends in visible leads more or less wide, and in parts subdivided in veins, over all the hills and mountains adjoining the main deposit. Among the sheets extracted, two are worth mentioning — especially one which on account of its almost fabulous size, weighing one hundred and forty-nine arrobas[SUP]1[/SUP], it was found necessary to employ the heat of four forges at the same time to reduce to a smaller bulk — the other weighed twenty-one arrobas, though according to other accounts it was much larger. The news of such immense lumps having been found, without the investment of much labor, could not fail to convey a great number of people to that region, not only from the neighboring settlements, but also from the most distance provinces. The amount of silver extracted within a very short period, amounted to 400 arrobas, or five tons.”

Another mine very rich in silver was the Arizona; the position of which is also lost. It was in search of this mine that Count Raousset de Boulbon [the “Little Wolf” — Baily] made his celebrated expedition into Sonora, whither he went, at first, in good faith and with peaceable intentions, though after he had been defrauded and attacked, he turned filibuster. There are persons who are ready to assert that the exact position of the Arizona mine is known; but the best informed say it is not.

- The Spanish arroba is one quarter of a quintal — which, in turn, is the load that can be carried by a donkey or mule. A quintal is equivalent to the English “hundredweight” — 100 pounds.

--- o0o ---

Almost all versions of this legend point out the combination of a remarkably hostile part of the world and very hostile native residents (Apache, Papago and Pima) made the Planchas de Plata very difficult to develop, once the prospect had been located. The dangers of the desert remain, so this is an excellent opportunity to again quote these words of wisdom from the old prospector Philip Baily:

The yarns that make up this story may be taken in any mood one chooses; but the deserts must be taken seriously.

To begin with, sadly, it must be acknowledged that West’s account was taken, word-for-word, from John S. Hittell’s Mining in the Pacific States of North America (San Francisco: 1861). So many authors helped themselves to West’s work it almost seems fair he did the same thing — although I will not defend such blatant plagiarism.

Now — what makes these seemingly simple tales so complex? There is the story of the name “Arizona.” And there is the question: are these two different prospects?

The Arizona was a legendary lost mine and the Planchas or Bolas de Plata a verified, if short-lived, silver placer if not actually a mine. But was the Planks, or Balls, of Silver located in the Arizona cañyon?

An absolutely essential work on the topic is the first-rate article by Adlai Feather (of Messila Park, New Mexico) — “Origin of the Name Arizona.” It appeared in the New Mexico Historical Review, April 1964 (Vol. XXXIX — No. 2). It is a masterful summary of the history of the Arizona “mine” which produced some 10,000 pounds of native silver, and of the origins of the Arizona name. It also briefly tells the story of Hugh Stephenson of El Paso, who financed a search in the Organ Mountains for the “Padre Mine.” His exploration party didn’t find it — but they did locate and he then developed a lode that turned out to be a million dollar silver mine! This is not the only time a hunt for fabled wealth has produced such unexpected — although quite happy - results.

Lost mine hunters will be interested in Feather’s page 99 footnote on the Padre Mine. “In 1879, a Lincoln County merchant named LaRue did a little exploration work at the site” of Frank Flecher’s claim in the San Andres Mountains, three miles north of the San Agustin Pass. Near a stone cabin a shallow cut and a shallow shaft just ten feet deep had been made. “Out of this jumble of indefinite information,” Feather continues, “emerged the legend of ‘The lost mine of Father LaRue.’”

Feather draws extensively on the 1850 work of Francisco Velasco. His book was translated by Wm. F. Nye and published as Sonora: Its Extent, Population, Natural Productions, Indian Tribes, Mines, Mineral Lands, Etc., Etc. (San Francisco: 1861). Apparently the appearance of this information in English led to a silver rush in the region.

Probert apparently considers the Mina de Planchas or Bolas de Plata (Feather, referenced above, states it was also known as the Minas de Bolas) to be the same — and he offers over three pages of sources. His “Anon., ‘Planks of Silver,’ Hand Book of Mining (publisher unknown), San Francisco, 1861, pg. 233” appears to be Hittell, cited above. The “Page 233” is probably a typo — the accounts are on pages 223 and 224.

It comes as no surprise that Ed Bartholomew (“Jesse Ed Rascoe”) discussed this famous find (“Old Spanish Mine Archives”) in The Golden Crescent; The Southwest Treasure Belt (Toyahvale, Texas: 1962). It is instructive that he used R.J. Hinton’s The Handbook to Arizona (1878) as a primary source. Hinton, in turn, quoted Howe, “a recognized authority and megallurgist.” I have not been able to locate which of Howe’s works Mr. Hinton quoted. Perhaps a more able researcher can shed light on that question. “Rascoe” also quotes H.G. Ward [Mexico in 1827] (1828) and Judge Wilson (1855-56).

Back to the story, however. There is an essential thread to this legend — and a useful primer in how lost mine yarns grow and flourish. Because when one digs deeper into the tale, the layers become more discernible.

Herbert Howe Bancroft discusses these mines in both the History of Arizona and New Mexico 1530-1888 (The Works of Herbert Howe Bancroft, Vol. XVII) (San Francisco: 1889) and his History of North Mexican States and Texas, Vol. I (San Francisco: 1884). As usual, he draws upon rare original Spanish documents and must at least be consulted.

Sylvester Mowry’s Arizona and Sonora; The Geography, History, and Resources of the Silver Region of North America (Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged) (New York: 1864) also quotes Ward on the bolas de plata as well as the Criaderos de Plata. He also states:

The name ARIZONA is undoubtly derived from the Aztec. In the original it was Arizuma, and the change is a corruption into the present word, which is accepted as Spanish. We have no decided information as to its meaning, but the impression among those who have been curious enough to investigate is, that it signifies “silver-bearing.” This impression gains strength from the fact that the Arizona mountains are very rich in silver, and that a tradition of a silver mine, called La Arizona, of incredible richness, still exists among the Mexican people near the frontier of our newly-acquired Territory.

Despite the assured presentation, it appears Lieut. Mowry was badly mistaken about the name (although not about the tradition of the rich La Arizona silver mine). The title of the essay by Donald T. Garate, Tumacácori's historian, Arizona (Never Arizonac) neatly sums up his contention — buttressed by considerable documentation. I recommend it.

Although Arizonac (the good oak trees), like Arizona (the good oak tree) is a perfectly viable Basque word, it was never used by the early settlers, soldiers, priests, and miners who lived there. The use of Arizonac is a twentieth century fable that needs to be corrected.

http://www.nps.gov/tuma/historyculture/upload/Arizonac Article.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2013.)

"Toward the end of last October, between the Guevayi Mission and the ranchería called Arizona, some balls and slabs of silver were discovered, one of which weighed more than one hundred arrobas (2,500 pounds), a sample of which I am sending to you, Most Illustrious Lord."

- Captain Juan Bautista de Anza to Bishop Benito Crespo, January 7, 1737.

http://www.nps.gov/tuma/historyculture/arizona-planchas-de-plata.htm

The classic Fantasies of Gold; Legends of Treasure and How They Grew by E.B. “Ted” Sayles (Tucson, Arizona: 1968) offers:

The earliest mining in the Southwest was in the 1700’s. The Spanish king had given mining grants to a select few who worked the rich surface, or shallow, silver deposits such as those west of Nogales, Arizona — only forty miles from Fort Huachuca [site of the “Sergeant Jones’ Treasure”].

These mines were known as the Planchas de Plata (planks of silver). The rich ore was carried south on the backs of burros to a refinery in Mexico or to some shipping place to be sent to Spain. In 1774, gold placers were worked at Quijotoa, north of Sells, Arizona, on the Papago Indian Reservation.

The essential Golden Mirages; The Story of the Lost Pegleg Mine, The Legendary Three Gold Buttes, and Yarns of and by Those Who Know the Desert by Philip A. Baily (New York: 1940) contends the Arizona, found near the Sierra del Pararito, just below the border and about fifteen kilometers southwest of Nogales, was also known as Las Bolas de Plata. This book covers several 19[SUP]th[/SUP] Century searches for this mina perdida — accounts not readily available elsewhere. Baily wrote a detailed account of the Planchas de Plata, pointing out it is both a lost and an “unlost” mine.

Indeed, stories of lost mines being found appear second in number only to accounts of mines being lost in the first place.

Long-time prospector and newspaper man (editor of the Tombstone Epitaph) Wayne Winters wrote “I Found the Planchas de Plata,” published in True West (May-June 1964 — Vol. 11, No. 5). This article does not appear to have been reprinted in GOLD! The mine is also discussed in Mr. Winters’ Campfires Along the Treasure Trail (Tombstone, Arizona: 1963).

The Lost Planchas de Plata Ledge is included in Robert G. Ferguson’s Campfire Tales of Lost Mines and Hidden Treasure (Privately Printed; Tucson, Arizona: 1937). I will let his version represent the countless accounts in lost mine books that can only be relied upon to offer re-worked tales with little novelty and even less accuracy taken from previous writers. It was presented in an issue of GOLD! (Summer 1971 — Vol. 3, No. 3. Ferguson’s pamphlet was enlarged and published as Lost Treasure; The Search for Hidden Gold by the vanity Vantage Press (New York: 1957). Some years later the unbound signatures were located and issued with card covers as a “paperback.” Because at that time the most expensive part of the printing process was the hardcover binding — after the first copy the expenses are only paper and press time — it was typical to bind only a small portion of the printed pages. The author was paying for the work. If demand was there, more copies could always be bound in hardcovers. Apparently it wasn’t. The Ward Ritchie Press (Los Angeles: 1973) reprinted it again as Guidebook to Lost Western Treasure; The Search for Hidden Gold. Now, because the copyright has expired (or, at least, that is the perception) there are modern reprints readily available.

Finally, Charles Rene Gaston Gustave de Raousset-Boulbon is mentioned in passing, above, in the excellent Golden Mirages. This French nobleman, gold prospector, filibuster and adventurer deserves considerably more attention than we can provide here. From his birth in Avignon to his death in the dust of Guaymas, Old Mexico, just thirty-seven years later, executed by firing squad (he distained the traditional blindfold), Count Raousset-Boulbon’s life was the stuff of legend.

My initial draft of these notes included “I sincerely hope someone will bring the extraordinary saga of this soldier of fortune to life — that’s a book I would very much like to read!” Rereading them, Baily’s “Little Wolf” rang a bell in my distant memory. I looked — and I have a copy of The Wolf Cub; The Great Adventures of Count Gaston de Raousset-Boulbon in California and Sonora 1850-1854 [translated from the French of Maurice Soulie] by Farrell Symonds (1927). Now I am very much looking forward to reading it!

--- o0o ---

This is Part IX and the final episode in the Lost Mines of the Desert West series, posted after another too-lengthy sabbatical. Part I — The Introduction - was posted December 26, 2008. Part II — “The Lost Arch” Diggings went up January 3, 2009. Part III — The Peg-Leg Mine; Or, the God of Fury’s Black Gold Nuggets, was made available January 11, 2009, and may be found under the Lost Peg Leg Mine topic. Part IV — The Lost Papuan Diggings — again saw the light of day on January 19, 2009. Part V — The Lost Dutch-Oven Mine — was posted January 27, 2009. Part VI — The Lost Breyfoggle [sic] appeared February 8, 2009. After a long hiatus Part VII — The Goler Placer Diggings — came out on April 26, 2011. Part VIII — The Lost Gun-Sight Mine — was posted on May 6, 2011. The only lost mine yarn told by Mr. West that has not been presented here is The Lost Tub Placer. That one this editor is saving for a book collection.

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

Last edited: