Crow

Silver Member

- Jan 28, 2005

- 3,726

- 10,361

- Detector(s) used

- ONES THAT GO BEEP! :-)

- Primary Interest:

- Other

Hello Gollum.

Here is case in example of how an Archeologist can easily fall from grace and his fellow Archie fall on him like a pack of Jackals. The Following story many archeologist fear falling into this situation as the profession of archeology is very competitive. 2% of Archeology students ever find employment in their profession.

The Following story

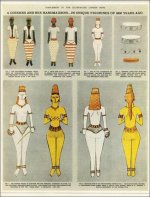

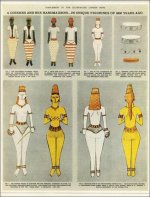

In 29 November 1959, the Illustrated London News ran a ‘FIRST AND EXCLUSIVE REPORT OF A CLANDESTINE EXCAVATION WHICH LED TO THE MOST IMPORTANT DISCOVERY SINCE THE ROYAL TOMBS OF UR’. Distinguished archaeologist James Mellaart listed the ‘Royal treasure of Dorak,’ named after the village in Turkey where they were unearthed.

The Dorak treasures included a gold statuette, silver-inlaid swords and daggers, and dismantled panels form a throne, complete with a gold sheet adorned with Egyptian hieroglyphics dating the finds to around 2473 BC. An engraving on one sword blade showed ‘certainly the earliest detailed representation of ocean-going ships outside Egypt’. So spectacular were the finds that Mellaart concluded that it was here in the ‘Yortan’ province neighbouring the contemporary Troy of King Priam, that Mediterranean civilization kick-started. Mellaart’s article was accompanied by drawings based on his own sketches of the impressive artefacts, with an apology that ‘Owing to the circumstances of this discovery’ there were no photos yet. A book on the ‘founders of civilization’ was promised soon, which would turn archaeology on its head.

Then things went a little crazy. None of the alleged Dorak treasures or any photos of them have shown ever up? The archaeological establishment soon doubted whether the finds had ever existed? The Dorak was hastily forgotten in an embarrassment level of earlier Piltdownian Affair that left many Archeological establish ment embarrassed and in disrepute.

James Mellaart, was a Dutchman by birth but was of Scottish descent. In 1951 he got a scholarship to study with the British Institute of Archaeology in Ankara, (BIAA), based in Turkey’s capital. He gained a reputation for his uncanny, knack, almost like ‘a water diviner’ of walking a potential site, reading the signs, picking a spot to excavate, and striking it rich almost immediately. By the time of the ‘Dorak affair’ in 1959 he already had made two sensational discoveries in Turkey to his name: the Neolithic site of Hacilar, found after following up on local gossip, and Çatal Hüyük, one of the ‘earliest sites of civilization,’ where hunter-gatherers made the leap to farming. From the beginning, Mellaart had a deep interest in the alleged Biblical ‘Sea People’ of the thirteenth millennium BC, who he thought may have lived along Turkey’s coast. James Mellaart thought he discovered evidence of the semi-mythical ‘Sea People’ in the Dorak hoard.

James Mellaart’s own account, he was on an evening train to Izmir in 1958, on his way to view artefacts in an Izmir museum. A girl entered and sat opposite him. She was, as Mellaart recalled ‘very attractive. And she wore a gold bracelet, reminiscent of the bracelets found at Troy. The girl, who spoke English with an American accent, introduced herself as Anna Papastrati and told him she had many bracelets at home like the one she wore, would Mellaart like to see them?

At her Izmir home, Anna showed Mellaart more gold artefacts, a bit at a time, ‘She seemed to be teasing me,’ Mellaart later observed. Some old, damaged, photos were produced, showing ‘skeletons in tombs’, with writing on them in modern Greek. There was a vague story about Anna’s family uncovering the tombs in the village of Dorak, on the shore of Lake Apolyont during the Greek-Turkish war in the early 1920s. Mellaart ended up staying three days at Anna’s house, making notes and sketching antiquities: an ‘erotic’ gold statue of a goddess holding her breasts, ceremonial axe heads and sceptres in marble and obsidian.

Anna eventually agreed to send Mellaart photos of the Dorak hoard at a later date. Only on leaving Anna’s house did Mellaart remember to ask for its address – 217 Kazim Dirik Street. Izmir was rapidly expanding at the time, and the street, now believed to be 1777 Street, changed its name at least four times since 1958. Four years later, the Turkish authorities couldn’t find the house, and said the district was a commercial zone with no residential properties. The promised photos of the Dorak hoard never came, but a curiously unconvincing typed letter signed ‘Love. Anna’ arrived for Mellaart, granting permission to use the sketches in an article.

Lacking any photographic evidence, the BIAA declined to sponsor publications on Dorak in archaeological journals, so Mellaart took it to Illustrated London News, which regularly ran archaeology features. Details changed in later versions of Mellaart’s Dorak story: he stayed a week instead of just three days, the Dorak incident had taken place several years earlier, There has been several versions of his statement but perahps he’d been sworn to secrecy, or he’d been afraid to tell his wife he’d spent more than several days at the house of a Beautiful strange woman?

The few people who saw Mellaart’s unpublished research on Dorak with rubbings from sword blades and drawn illustrations are convinced that this work is too elaborate for Mellaart to have made up? And there was no benifet of him doing that anyway?

Some speculate that most likely explanation for the Dorak hoard is that some of it was genuine, looted from sites around Turkey, mixed in with fakes, and a single genuine Egyptian piece to (fraudulently) date it. ‘Anna’ was a plant, a honey-trap to lure a respected archaeologist into authenticating the hoard, with a view to selling it to a millionaire collector abroad? many speculate that the US, Greece or Egypt could be likely destinations for the Dorak treasure, whatever it was? The Turkish authorities believe this. A Turkish newspaper claimed Mellaart was part of a plot to smuggle 48 million-worth of Dorak ‘national treasures’ out of Turkey. Smuggling charges was brought against Mellaart in 1962, which was dropped in a general amnesty in 1965. Turkey’s Department of Antiquities refused Mellaart all further permits to excavate in the country. His Career as an archeologist was finished.

Interest in Dorak slipped out of the annals of archaeology and into the realms of mystery and long lasting warning to Archies. And strange enough if you go to look at the British Library’s microfilm copy of Mellaart’s original 1959 Illustrated London News article today you will find the four unnumbered pages of colour plates showing drawings of the Dorak treasures had been torn out!

Crow

Here is case in example of how an Archeologist can easily fall from grace and his fellow Archie fall on him like a pack of Jackals. The Following story many archeologist fear falling into this situation as the profession of archeology is very competitive. 2% of Archeology students ever find employment in their profession.

The Following story

In 29 November 1959, the Illustrated London News ran a ‘FIRST AND EXCLUSIVE REPORT OF A CLANDESTINE EXCAVATION WHICH LED TO THE MOST IMPORTANT DISCOVERY SINCE THE ROYAL TOMBS OF UR’. Distinguished archaeologist James Mellaart listed the ‘Royal treasure of Dorak,’ named after the village in Turkey where they were unearthed.

The Dorak treasures included a gold statuette, silver-inlaid swords and daggers, and dismantled panels form a throne, complete with a gold sheet adorned with Egyptian hieroglyphics dating the finds to around 2473 BC. An engraving on one sword blade showed ‘certainly the earliest detailed representation of ocean-going ships outside Egypt’. So spectacular were the finds that Mellaart concluded that it was here in the ‘Yortan’ province neighbouring the contemporary Troy of King Priam, that Mediterranean civilization kick-started. Mellaart’s article was accompanied by drawings based on his own sketches of the impressive artefacts, with an apology that ‘Owing to the circumstances of this discovery’ there were no photos yet. A book on the ‘founders of civilization’ was promised soon, which would turn archaeology on its head.

Then things went a little crazy. None of the alleged Dorak treasures or any photos of them have shown ever up? The archaeological establishment soon doubted whether the finds had ever existed? The Dorak was hastily forgotten in an embarrassment level of earlier Piltdownian Affair that left many Archeological establish ment embarrassed and in disrepute.

James Mellaart, was a Dutchman by birth but was of Scottish descent. In 1951 he got a scholarship to study with the British Institute of Archaeology in Ankara, (BIAA), based in Turkey’s capital. He gained a reputation for his uncanny, knack, almost like ‘a water diviner’ of walking a potential site, reading the signs, picking a spot to excavate, and striking it rich almost immediately. By the time of the ‘Dorak affair’ in 1959 he already had made two sensational discoveries in Turkey to his name: the Neolithic site of Hacilar, found after following up on local gossip, and Çatal Hüyük, one of the ‘earliest sites of civilization,’ where hunter-gatherers made the leap to farming. From the beginning, Mellaart had a deep interest in the alleged Biblical ‘Sea People’ of the thirteenth millennium BC, who he thought may have lived along Turkey’s coast. James Mellaart thought he discovered evidence of the semi-mythical ‘Sea People’ in the Dorak hoard.

James Mellaart’s own account, he was on an evening train to Izmir in 1958, on his way to view artefacts in an Izmir museum. A girl entered and sat opposite him. She was, as Mellaart recalled ‘very attractive. And she wore a gold bracelet, reminiscent of the bracelets found at Troy. The girl, who spoke English with an American accent, introduced herself as Anna Papastrati and told him she had many bracelets at home like the one she wore, would Mellaart like to see them?

At her Izmir home, Anna showed Mellaart more gold artefacts, a bit at a time, ‘She seemed to be teasing me,’ Mellaart later observed. Some old, damaged, photos were produced, showing ‘skeletons in tombs’, with writing on them in modern Greek. There was a vague story about Anna’s family uncovering the tombs in the village of Dorak, on the shore of Lake Apolyont during the Greek-Turkish war in the early 1920s. Mellaart ended up staying three days at Anna’s house, making notes and sketching antiquities: an ‘erotic’ gold statue of a goddess holding her breasts, ceremonial axe heads and sceptres in marble and obsidian.

Anna eventually agreed to send Mellaart photos of the Dorak hoard at a later date. Only on leaving Anna’s house did Mellaart remember to ask for its address – 217 Kazim Dirik Street. Izmir was rapidly expanding at the time, and the street, now believed to be 1777 Street, changed its name at least four times since 1958. Four years later, the Turkish authorities couldn’t find the house, and said the district was a commercial zone with no residential properties. The promised photos of the Dorak hoard never came, but a curiously unconvincing typed letter signed ‘Love. Anna’ arrived for Mellaart, granting permission to use the sketches in an article.

Lacking any photographic evidence, the BIAA declined to sponsor publications on Dorak in archaeological journals, so Mellaart took it to Illustrated London News, which regularly ran archaeology features. Details changed in later versions of Mellaart’s Dorak story: he stayed a week instead of just three days, the Dorak incident had taken place several years earlier, There has been several versions of his statement but perahps he’d been sworn to secrecy, or he’d been afraid to tell his wife he’d spent more than several days at the house of a Beautiful strange woman?

The few people who saw Mellaart’s unpublished research on Dorak with rubbings from sword blades and drawn illustrations are convinced that this work is too elaborate for Mellaart to have made up? And there was no benifet of him doing that anyway?

Some speculate that most likely explanation for the Dorak hoard is that some of it was genuine, looted from sites around Turkey, mixed in with fakes, and a single genuine Egyptian piece to (fraudulently) date it. ‘Anna’ was a plant, a honey-trap to lure a respected archaeologist into authenticating the hoard, with a view to selling it to a millionaire collector abroad? many speculate that the US, Greece or Egypt could be likely destinations for the Dorak treasure, whatever it was? The Turkish authorities believe this. A Turkish newspaper claimed Mellaart was part of a plot to smuggle 48 million-worth of Dorak ‘national treasures’ out of Turkey. Smuggling charges was brought against Mellaart in 1962, which was dropped in a general amnesty in 1965. Turkey’s Department of Antiquities refused Mellaart all further permits to excavate in the country. His Career as an archeologist was finished.

Interest in Dorak slipped out of the annals of archaeology and into the realms of mystery and long lasting warning to Archies. And strange enough if you go to look at the British Library’s microfilm copy of Mellaart’s original 1959 Illustrated London News article today you will find the four unnumbered pages of colour plates showing drawings of the Dorak treasures had been torn out!

Crow