Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,474

- 3,797

The 1867 Schnively Expedition - Parts One & Two

I don’t like posting an article that isn’t complete. However, I’m sharing what I have so far because of the interest expressed in the topic – and it is going to be some time before I successfully locate my missing notes and other papers.

This is, in my opinion, a prime example of stories that deserve more play than they have received. Rather than re-hash the tired legends and yarns, authors would be advised to research and write up tales that will probably be new to most readers.

Anyone interested in Jacob Snively (and one of the challenges to the researcher is the bewildering variety of ways his name has been spelled) should turn to the two great writers on Texas treasures: Ed Bartholomew (“Jesse Rascoe”) tells this story in The Golden Crescent (1962) and J. Frank Dobie touches on "the highly romantic second expedition" in Legends of Texas (1924). Both those works are, of course, highly recommended. And not just for this story!

This account was written and published by J. Warren Hunter. However, further research disclosed a remarkably similar account: “Reminiscences of the Schnively Expedition of 1867” by A. Whitehurst, published in the Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association (January 1905 – Vol. 8, No. 3).

Following is Mr. Hunter’s article with additions, in italics, from the Whitehurst account.

By John Warren Hunter, Hunter's Magazine (1911)

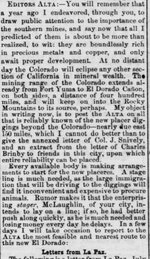

In the fall of 1866 Jacob Schnively, an enthusiast in mine prospecting, and Col. William Cornelius Dalrymple of Williamson County, created a stir of excitement among the people of the then Western and Northwestern border, over the alleged discovery of a very rich gold mine in the Sierra Nevada mountains on the Rio Grande. Mr. Schnively represented that he had prospected for gold in the Sierra Mountains and that he had discovered one of the richest mines on the continent in those mountains below El Paso and on the Texas side of the Rio Grande. In proof of his assertion he kept on display a fine collection of galena quartz and various samples of mineral, all extremely rich and which, as he claimed, had been taken from the vast inexhaustible deposits with his own hands.

But to develop this mine and to garner its untold wealth, required some capital, and a good number of men, and in order to enlist able bodied men in the enterprise, he offered to give each man who enlisted in the expedition and remained faithful, a share in the mine and also an interest in the land which was to be located by certificate. Colonel Dalrymple was among the first to become interested in the proposition. He was an old Indian fighter, an experienced frontiersman, and a man of considerable influence. Schnively's plan was to organize a company of thirty or forty men, but Colonel Dalrymple argued that ten men of his selection would be sufficient to overcome any hostile opposition on the part of Indians and that the smaller the number the greater the value of each stockholder's share in the mine.

His contention prevailed and he selected the following men to accompany the expedition: Mose[s?] Carson, an aged brother of the celebrated Kit Carson; Tom Jones, Tom Holly, John Cohen, Abe Hunter, Malcolm Hunter, Warren Hunter, Temp Robinson, "Bud" (W. H.) Robinson and A. Whitehurst, having made the trip through the country near the place where the gold mine was supposed to be, was selected for a guide, ten in all, and each one a frontiersman of known courage, marksmanship and endurance.

Mr. Carson was quite old but still active and full of energy. He was in the Mier expedition in 1842 and was one of the number who escaped execution at Salado by drawing a white bean.

The story of this first organization, the start upon the expedition and its signal failure is best told by Mr. W. H. ("Bud") Robinson, who was shot and killed at his home near Fort Chadbourne on the Colorado, in 1911.

“In January, 1867, Colonel W. C. Dalrymple, E. V. Schnively, and Mose Carson, who was then 87 years old, came to my fathers' ranch near old Camp Colorado. They were organizing a party, to go a gold prospecting trip to a certain described mountain 40 miles east of the Rio Grande and not a great distance from Fort Quitman. For some time prior to the coming of these gentlemen, there had been nothing doing in our section of the country. The Indians hadn't been down in the settlements for quite awhile and times were awfully dull, more especially was this case with those of us who had been used to fighting either Indians or Yankees. Dalrymple and Schnively wanted men to go with them on a gold hunt; Schnively knew where the mine was located, he had been there and had samples of the pure stuff to show. There was gold in endless quantity and untold wealth awaited each man who became a member of the expedition. The trip promised excitement, adventure, and a better knowledge of the vast region that bordered on the Rio Grande, and this, taken in connection with the prospect of great wealth and coffers of gold, induced sixteen of us to enlist for the expedition and we were ready to be off at once. Besides the three already mentioned there were Dr. McReynolds, Warren and Abe Hunter, Tom Jones, Tom Holly, my brother, myself, and a man by the name of Greenwood. There were five other men whose names I have forgotten. You must bear in mind that forty-three years have elapsed since that time and my memory is not as clear now as it was two score years ago. Each member of the expedition was required to furnish his own mount, arms, ammunition — everything, and was to share equally in the ownership and profit of the mine. With the required equipment and a good six months’ supply of provisions carried on pack mules we met at Camp Colorado, organized and took up the line of march for the new El Dorado, and proceeded without mishap until on the morning of February 3[SUP]rd[/SUP]. We came to the old overland stage road — then a grass grown trail — on the North Concho about where Sterling City now stands. We followed along this dim stage road and had gone only a few miles when we ran across a trail but recently made by a bunch of horses and leading off in a northwest course.

“Tom Jones and I were riding some little distance in the rear and those in front, having examined the trail, decided it was that of a bunch of mustangs and passed on. When Tom and I came to the trail we decided to give it a more careful inspection and after following it a few hundred yards we were convinced that it was made by a large party of Indians, whereupon we left the trail and galloping up to Col. Dalrymple and Schnively, I told them of my observations. They advanced the idea that it was a trail made by wild horses which were numerous in that section at that time, I pointed out the fact well known to all plainsmen, that mustangs never kept in a bee-line course, nor did they ever travel in single file, but zig-zagged more or less to the right or left, while horses ridden by Indians were always guided in a straight course and did not sway either to the left or right.

“I further told Col. Dalrymple who was in command of the expedition, that I believed we were in danger and that we were entirely too careless, and urged him to have the men and our pack horses kept in closer marching order.

Old Mose Carson advised greater caution, but Dr. Reynolds tantalized me by saying that I was too easily excited and was ready to be scared by every mustang track that chanced to appear in our path.

“'All right, Doctor,' I said, 'you'll learn to distinguish the trail of a herd of mustangs from that of a bunch of Comanches before any of us are much older and if you don't hear the war whoop before sun-rise tomorrow, I'll be very much disappointed. That trail is fresh and this minute some of the bead-eyed scoundrels may be watching us from one of those peaks in the distance.’

"During the remainder of the day better discipline was observed; the men kept closer together and nearer our pack animals. Late that evening we camped on what was then known as Bat Creek, to kill buffalo and cure as much buffalo meat as we could carry with us, but since the time we camped there it has been known as Kiowa Creek, and which flows into the Concho River. We met five men from San Saba, John Murray, Dr. McBunnels, and three others whose names I have forgotten. They had heard of our expedition, and had come there to meet us. We had some parleying and discussion before we could agree to let them join us, but, as they were good men and had some so far for that purpose, we consented to take them with us. Besides they had more buffalo meat already cured then we could very well carry. We kept a close watch over our stock all night and remained in camp until 11 o'clock next day in order to give our stock a chance to graze, having been tied up and under guard all the night before.

“No Indians having appeared by this time, the trail had subsided and our vigilance was supplanted by the usual neglect and carelessness that follow men inured to danger. The men mounted and set off without any regard to order and our leader showed about as much indifference as some of his men.

We remained in camp on the Concho two days. We packed our mules with nice, well-cured buffalo meat, and one morning as the sun arose we set out for the head of the Concho only ten miles beyond.

"Holly and Greenwood were mounted on mules and were the last to leave camp.

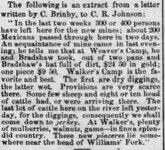

Tom Jones and I were slightly in the rear of the main party which reached a point about six hundred yards from where we had camped when we heard the yells and the screams of Tom Holly, who had left his gun at camp, and Greenwood, calling for help, a quarter of a mile behind when [t]he[y] discovered a couple of the red devils trying to cut [t]he[m] off from us. On looking back, we saw two columns of Indians coming single file over the little rise near the camp we had just abandoned. Each band was led by a chief and they were coming pell mell and yelling like demons right on the heels of Holly and Greenwood who were howling for help and making tracks for dear life. Greenwood was belaboring his mule, fore and aft, with a heavy breech-loading rifle while Holly was laying on manfully with the steel ramrod of his Enfield musket. The alarm was given, and our party now saw that a fight was inevitable. Col. Dalrymple cried out: ‘Boys, now we have got hold our packs and fight – fight for our lives, for just look, they are coming from every direction!’ On our right there was a band that appeared to number as many as a hundred, and before us there were equally as many. They had planned the attack, no doubt, while we were in camp at the mouth of Kiowa creek. They would have been successful in their plan if Tom Holly had not made the trip back to camp, for had we proceeded a mile further we would have been at least two miles out on a level, open flat, where there were no natural fortifications whatever. Being the nearest to them, Jones and I wheeled our horses and were soon at their side. This checked the foremost Indians for an instant and saved our two comrades. Although in close range, the Indians did not fire on us when we hastened to the relief of these two men, and why they withheld their fire has always been a mystery I could never solve. There were at the lowest estimate, two hundred of them, well mounted, while we were but four, and they could have easily dispatched us before our comrades could have reached us, and right here I want to say that during the Civil War, then but recently closed, I had participated in fifty-two battles and had served under some of the most skillful cavalry officers in the Confederate army east of the Mississippi, but I had never seen a commander handle his troops with the judgment and skill displayed by a Kiowa chief on that fateful occasion.

“During this hard fought battle, which lasted the rest of the day — say from 11 0'clock until after dark — that chief's maneuvers were in full view and his tactics won the admiration of every ex-Confederate soldier in our little band. Altho' within easy hearing distance, we never heard him give a word of command. A motion of the hand, the pointing of his long lance, or the flourish of his highly decorated shield, seemed to be as clearly understood by his warriors as his words of command could possibly have been. He was decked out in all the paraphernalia of savage warfare, was mounted on a superb bay gelding and seemed to rank the Comanche chief whose costume was less ostentatious and who bestrode a very fine gray.

"Instead of firing on us when we reached Holly and Greenwood, this Kiowa chief seemed to hold up, giving us time to rejoin our comrades who had started back to our relief, and when we had rallied and had made ready to give them a hot reception, he led his men in single file and in perfect order past us, and when he reached a point due west of us and with the utmost coolness and precision formed his men — fully one hundred — in a hollow square. At the same time, and while this movement was in progress, the Comanche chief with about the same number of warriors, led his men back a short distance and drew up in line, their intention, evidently, being to cut us off from the Concho, which was not very distant, and as we soon realized, afforded our only means of defense and ultimate escape, as we were outnumbered more than twelve to one.

"When the Kiowas formed their hollow square they advanced and opened a heavy fire, or more properly speaking, a heavy discharge of arrows, as only a few of them had guns. I counted only four guns in the entire outfit but several had pistols and nearly or quite all carried lances. Each of our men was armed with either an Enfield or Spencer rifle and carried from one to two six shooters and when the Kiowas advanced within our reach, we began to empty their old saddles, but the Kiowa chief held his men steady in line, at the same time employing his shield to ward off the many shots we fired at him.

“‘Shoot that chief!' came from every man in our party, but he seemed invulnerable behind that shield. Captain Schnively lost his head and ordered us to dismount and fight on foot, but some of the men cursed him for being a fool. Col. Dalrymple ordered ten of the men to hold the pack animals, and five others to charge through the Indians who were between us and the Concho. [He] shouted to the boys: 'Stay on your horses boys, draw your pistols and we'll charge 'em!' and with a yell he himself lead the charge we went right in among them, shooting right and left, and they broke. As we sallied in among them, Tom Jones' horse was killed and he fell. Jones recovered his feet bravely in time to parry the thrust of a lance in the hands of an Indian mounted on a splendid horse. Seizing the bridle reins Jones shot the Indian and mounted his horse.

"When we made this charge we had to leave our pack animals for the time being without protection, seeing which the Comanches made an effort to capture them but when they saw their allies, the Kiowas repulsed, they swung round and joined forces. This enabled them to rally and to once more present a bold front. Seeing that our stock were scattering and were liable to capture and that there was a possibility of getting them to the creek, Col. Dalrymple ordered me and my brother to round them up and try to get them to the creek and then turning to the men he said: 'Boys, the scoundrels ain't whipped yet; We '11 have to go right in among them again, and the pick of the herd and one hundred dollars in gold to the man that gets their chief!' The Colonel led the charge, but they held their ground with dogged determination. Several of our horses were killed and more than half our men were wounded more or less severely in this hand-to-hand struggle.

“Col. Dalrymple received a lance thrust through the fleshy part of the arm just below the shoulder, and when the Indian attempted to withdraw it, the barbs of the blade caught in the tendons and muscles of the arm and held fast. Warren Hunter, seeing the Indian tugging at the lance, shot him and his horse having been killed he seized and mounted the fallen Indian's horse. When we, my brother and I, saw the desperate mix-up and that it was going hard with the boys, we abandoned the pack animals and hastened to their relief. Our comrades were gradually yielding, that is giving back, and the Indians were slowly closing round them. They tried to cut us off but we went in with a whoop.

“The boys were somewhat scattered, every man fighting on his own hook. Col.

Dalrymple was holding his own, although encumbered with that lance which was still hanging to his arm. His family still hold it as a relic of the event. When we left the pack animals and started to his relief, and failing to head us off, six Indians got in between us and Dalrymple, thus cutting him off. By this-time his gun and pistols were empty and his only hope was in tail running. He made a break with the lance dangling from his arm, and the six Indians close in after him, my brother and I following right on their heels shooting and yelling. This race was continued for about three hundred yards when the Indians finding themselves going too far from the main body and our fire getting too hot for them, gave up the pursuit and making a circuitous run, rejoined their comrades. Here we found a rallying point for our hard-pressed men and around which the boys soon gathered. It chanced to be near the creek or river which after all was no other than a small stream at this point. The boys fell back to this point fighting, and when we had all collected, the Indians made another charge but were repulsed. As they fell back they rounded up our pack animals, thus capturing all our packs and provisions. In this charge they wounded my horse, rendering him unfit for further service.

“When the Indians fell back, we felt that the worst was yet to come, we had killed and wounded a large number of their warriors and several of their horses and being desperate over their losses and having us at all disadvantages, doubtless they would never give up the contest so long as one of us survived. We improved the time allowed us in preparing for the final struggle which every one of us believed was near at hand. We assisted Colonel Dalrymple from his horse, (he was a large, fleshy man), released the lance from his arm and bound the wound with a handkerchief. He begged for water and I went to the creek near by and brought water in my hat, of which he drank copiously. By this time Tom Jones had found a more secure place, a little ravine or gully that entered the Concho, and to this point we hastened. The banks were very low and while they afforded little protection it was safer there than out in the open. Our pack mules were all killed while on the retreat, and the packs, which contained the bulk of our ammunition and all of our food, were captured. While all this was going on in our locality, the Indians dismounted a number of their bucks and placed them on a high bluff on the opposite side of the creek and overlooking our position, while another party occupied the bed of the creek in our front. Those on the bluff were about 150 yards from us and while they were getting in position several of them bit the dust and we could see their comrades dragging them to the rear just beyond the crest of the bluff. I had cautioned the boys lying close to me to never shoot at a shield as it would be a useless waste of ammunition, but to always take aim at the hips, the legs or the lower part of the abdomen, just below the lower rim of the shield.

Old George Carons was eighty or ninety years of age and bald-headed, and the Indians apparently respected his age and his baldness; otherwise they would have killed him, as he was the last to reach the place of refuge. In the charge he dismounted and case leading his horse as though nothing unusual was happening. Colonel Dalrymple also led his horse in.

“In our first charge we had killed the Kiowa chief's fine horse and now, mounted on another steed we saw him marshalling his braves and by this we knew they were preparing for another desperate charge. Col. Dalrymple had somewhat regained his fighting strength and said to us: 'Boys they are going to come at us again. You fellows be good and ready, keep cool, lay low, select your Indian as they come up, hold a bead on him, and don't fire until I give the word and then if they don't stop let every man rise and with back-to-back we'll sell out.' Colonel Dalrymple, because of his wound, could not use his right arm. With fierce yells and the shaking of shields and lances the Indians came down in a furious charge and it seemed to me that Dalrymple would allow the Indians to ride right over us before giving the order to fire and thinking that an arrow may have knocked him out, I glanced over my shoulder to see what had become of him. I saw that he was all right and had just got my bead on one of the charging rascals and when they were within thirty feet of us, Col. Dalrymple yelled 'Fire!' and from the confused mix-up that followed the roar of our guns, 1 think every man in our outfit emptied a saddle. Some of the riderless horses actually ran over some of our men, who had risen to a stooping posture after the first fire, and were still pumping lead into the fleeing savages, most of whom milled around long enough to recover a few of their dead and wounded. Our deadly fire had completely staggered them for the time being, but after a short respite they rallied and came again and met with a second repulse which was more serious, apparently, than the first. The Kiowa chief rallied his men for the third and last final charge. They were in full view and we watched the chief while he rode up and down his line. Owing to the distance we could not hear his voice but could see his vehement gestures, all that indicated that he was delivering to his braves one of his most eloquent exhortations.

"During all this time we were not idle, but rather making every preparation for the onslaught. The first excitement of battle that too often addles men's heads and in which they become unnerved, had worn off and each man was cool and confident, although suffering from wounds more or less severe and each member of the party was being tortured with a consuming thirst for water, yet, we were sure of whipping the red scoundrels. And here, even in this dire extremity and in the face of impending death, the humorous Jest was not lacking. We saw the chief suddenly wheel and lead off, his men following, but when they reached a point one hundred yards from us, every Indian turned tail, threw his shield over his back, and sped away as if the devil himself were at his heels reaching for his topknot. Finding himself alone, the chief shook his lance defiantly at us, cursed us in Spanish as 'cabrones,' and 'hijos del Diablo,' then wheeling his horse he lit out after his skeedadling braves.

After we had taken our stand in the revine the Indians, failing to rout us, commenced killing our horses, piling them around us on every side, and at the same time making for us very good breastworks.

"During these three charges, those who occupied the bluff, annoyed us incessantly. One of them had an Enfield rifle and nearly every shot brought down one of our horses. To silence this fellow was of the utmost importance, and we didn't have to wait very long for the coveted opportunity.

"When the third charge was repulsed the enemy changed tactics. Those in front retired beyond view and later, numbers of them were seen gathering with them on the bluff, while still others, who had dismounted, were attempting to crawl upon us through the tall grass. Several of their dead still lay in the grass in our front and these they wanted to recover either by stealth or strategy. They crept uncomfortably close to us but not one of them dared show his head. They discharged arrows almost straight up in the air so that in their decent they might strike some of us, point foremost. For a short time the air was filled with these missiles, but owing to a high wind that blew out of the northwest, they were deflected and carried beyond their intended mark, although many of them fell near us, some coming down with a force that broke the shaft. This unusual target practice lasted nearly an hour. While this 'sky shooting' was in progress some of the men saw the grass moving against the wind in our front. Evidently an Indian was crawling up to tie a rope about the body of a dead comrade that lay where he fell, and a close watch was kept on that particular point. Presently a feather was seen bobbing up and down and a little later a black head was raised as if to get his bearings. There was a shot — and another dead Indian.

“The Indian with the Enfield on the bluff was next disposed of. He was perched behind a rock or boulder on the brink of the elevation and we had wasted a lot of lead trying to put him out of business. I had tried to pick him off several times and had failed, but finally I got the distance down fine and drew a bead on the little opening by the boulder where he stuck his head when he rose to fire, and when his black noggin darkened this opening, I let drive and knocked the whole top of his head off. When the ball struck him he made a wild leap, fell over the ledge and rolled to the base of the bluff. This silenced the long range Enfield, but not until about all our horses were killed.

== End of Part One ==

Good luck to all,

~The Old Bookaroo

I don’t like posting an article that isn’t complete. However, I’m sharing what I have so far because of the interest expressed in the topic – and it is going to be some time before I successfully locate my missing notes and other papers.

This is, in my opinion, a prime example of stories that deserve more play than they have received. Rather than re-hash the tired legends and yarns, authors would be advised to research and write up tales that will probably be new to most readers.

Anyone interested in Jacob Snively (and one of the challenges to the researcher is the bewildering variety of ways his name has been spelled) should turn to the two great writers on Texas treasures: Ed Bartholomew (“Jesse Rascoe”) tells this story in The Golden Crescent (1962) and J. Frank Dobie touches on "the highly romantic second expedition" in Legends of Texas (1924). Both those works are, of course, highly recommended. And not just for this story!

This account was written and published by J. Warren Hunter. However, further research disclosed a remarkably similar account: “Reminiscences of the Schnively Expedition of 1867” by A. Whitehurst, published in the Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association (January 1905 – Vol. 8, No. 3).

Following is Mr. Hunter’s article with additions, in italics, from the Whitehurst account.

The Ill-Fated 1867 Schnively Expeditions;

Bud Robinson’s Story

Bud Robinson’s Story

By John Warren Hunter, Hunter's Magazine (1911)

In the fall of 1866 Jacob Schnively, an enthusiast in mine prospecting, and Col. William Cornelius Dalrymple of Williamson County, created a stir of excitement among the people of the then Western and Northwestern border, over the alleged discovery of a very rich gold mine in the Sierra Nevada mountains on the Rio Grande. Mr. Schnively represented that he had prospected for gold in the Sierra Mountains and that he had discovered one of the richest mines on the continent in those mountains below El Paso and on the Texas side of the Rio Grande. In proof of his assertion he kept on display a fine collection of galena quartz and various samples of mineral, all extremely rich and which, as he claimed, had been taken from the vast inexhaustible deposits with his own hands.

But to develop this mine and to garner its untold wealth, required some capital, and a good number of men, and in order to enlist able bodied men in the enterprise, he offered to give each man who enlisted in the expedition and remained faithful, a share in the mine and also an interest in the land which was to be located by certificate. Colonel Dalrymple was among the first to become interested in the proposition. He was an old Indian fighter, an experienced frontiersman, and a man of considerable influence. Schnively's plan was to organize a company of thirty or forty men, but Colonel Dalrymple argued that ten men of his selection would be sufficient to overcome any hostile opposition on the part of Indians and that the smaller the number the greater the value of each stockholder's share in the mine.

His contention prevailed and he selected the following men to accompany the expedition: Mose[s?] Carson, an aged brother of the celebrated Kit Carson; Tom Jones, Tom Holly, John Cohen, Abe Hunter, Malcolm Hunter, Warren Hunter, Temp Robinson, "Bud" (W. H.) Robinson and A. Whitehurst, having made the trip through the country near the place where the gold mine was supposed to be, was selected for a guide, ten in all, and each one a frontiersman of known courage, marksmanship and endurance.

Mr. Carson was quite old but still active and full of energy. He was in the Mier expedition in 1842 and was one of the number who escaped execution at Salado by drawing a white bean.

The story of this first organization, the start upon the expedition and its signal failure is best told by Mr. W. H. ("Bud") Robinson, who was shot and killed at his home near Fort Chadbourne on the Colorado, in 1911.

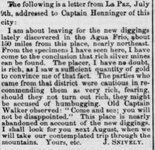

“In January, 1867, Colonel W. C. Dalrymple, E. V. Schnively, and Mose Carson, who was then 87 years old, came to my fathers' ranch near old Camp Colorado. They were organizing a party, to go a gold prospecting trip to a certain described mountain 40 miles east of the Rio Grande and not a great distance from Fort Quitman. For some time prior to the coming of these gentlemen, there had been nothing doing in our section of the country. The Indians hadn't been down in the settlements for quite awhile and times were awfully dull, more especially was this case with those of us who had been used to fighting either Indians or Yankees. Dalrymple and Schnively wanted men to go with them on a gold hunt; Schnively knew where the mine was located, he had been there and had samples of the pure stuff to show. There was gold in endless quantity and untold wealth awaited each man who became a member of the expedition. The trip promised excitement, adventure, and a better knowledge of the vast region that bordered on the Rio Grande, and this, taken in connection with the prospect of great wealth and coffers of gold, induced sixteen of us to enlist for the expedition and we were ready to be off at once. Besides the three already mentioned there were Dr. McReynolds, Warren and Abe Hunter, Tom Jones, Tom Holly, my brother, myself, and a man by the name of Greenwood. There were five other men whose names I have forgotten. You must bear in mind that forty-three years have elapsed since that time and my memory is not as clear now as it was two score years ago. Each member of the expedition was required to furnish his own mount, arms, ammunition — everything, and was to share equally in the ownership and profit of the mine. With the required equipment and a good six months’ supply of provisions carried on pack mules we met at Camp Colorado, organized and took up the line of march for the new El Dorado, and proceeded without mishap until on the morning of February 3[SUP]rd[/SUP]. We came to the old overland stage road — then a grass grown trail — on the North Concho about where Sterling City now stands. We followed along this dim stage road and had gone only a few miles when we ran across a trail but recently made by a bunch of horses and leading off in a northwest course.

“Tom Jones and I were riding some little distance in the rear and those in front, having examined the trail, decided it was that of a bunch of mustangs and passed on. When Tom and I came to the trail we decided to give it a more careful inspection and after following it a few hundred yards we were convinced that it was made by a large party of Indians, whereupon we left the trail and galloping up to Col. Dalrymple and Schnively, I told them of my observations. They advanced the idea that it was a trail made by wild horses which were numerous in that section at that time, I pointed out the fact well known to all plainsmen, that mustangs never kept in a bee-line course, nor did they ever travel in single file, but zig-zagged more or less to the right or left, while horses ridden by Indians were always guided in a straight course and did not sway either to the left or right.

“I further told Col. Dalrymple who was in command of the expedition, that I believed we were in danger and that we were entirely too careless, and urged him to have the men and our pack horses kept in closer marching order.

Old Mose Carson advised greater caution, but Dr. Reynolds tantalized me by saying that I was too easily excited and was ready to be scared by every mustang track that chanced to appear in our path.

“'All right, Doctor,' I said, 'you'll learn to distinguish the trail of a herd of mustangs from that of a bunch of Comanches before any of us are much older and if you don't hear the war whoop before sun-rise tomorrow, I'll be very much disappointed. That trail is fresh and this minute some of the bead-eyed scoundrels may be watching us from one of those peaks in the distance.’

"During the remainder of the day better discipline was observed; the men kept closer together and nearer our pack animals. Late that evening we camped on what was then known as Bat Creek, to kill buffalo and cure as much buffalo meat as we could carry with us, but since the time we camped there it has been known as Kiowa Creek, and which flows into the Concho River. We met five men from San Saba, John Murray, Dr. McBunnels, and three others whose names I have forgotten. They had heard of our expedition, and had come there to meet us. We had some parleying and discussion before we could agree to let them join us, but, as they were good men and had some so far for that purpose, we consented to take them with us. Besides they had more buffalo meat already cured then we could very well carry. We kept a close watch over our stock all night and remained in camp until 11 o'clock next day in order to give our stock a chance to graze, having been tied up and under guard all the night before.

“No Indians having appeared by this time, the trail had subsided and our vigilance was supplanted by the usual neglect and carelessness that follow men inured to danger. The men mounted and set off without any regard to order and our leader showed about as much indifference as some of his men.

We remained in camp on the Concho two days. We packed our mules with nice, well-cured buffalo meat, and one morning as the sun arose we set out for the head of the Concho only ten miles beyond.

"Holly and Greenwood were mounted on mules and were the last to leave camp.

Tom Jones and I were slightly in the rear of the main party which reached a point about six hundred yards from where we had camped when we heard the yells and the screams of Tom Holly, who had left his gun at camp, and Greenwood, calling for help, a quarter of a mile behind when [t]he[y] discovered a couple of the red devils trying to cut [t]he[m] off from us. On looking back, we saw two columns of Indians coming single file over the little rise near the camp we had just abandoned. Each band was led by a chief and they were coming pell mell and yelling like demons right on the heels of Holly and Greenwood who were howling for help and making tracks for dear life. Greenwood was belaboring his mule, fore and aft, with a heavy breech-loading rifle while Holly was laying on manfully with the steel ramrod of his Enfield musket. The alarm was given, and our party now saw that a fight was inevitable. Col. Dalrymple cried out: ‘Boys, now we have got hold our packs and fight – fight for our lives, for just look, they are coming from every direction!’ On our right there was a band that appeared to number as many as a hundred, and before us there were equally as many. They had planned the attack, no doubt, while we were in camp at the mouth of Kiowa creek. They would have been successful in their plan if Tom Holly had not made the trip back to camp, for had we proceeded a mile further we would have been at least two miles out on a level, open flat, where there were no natural fortifications whatever. Being the nearest to them, Jones and I wheeled our horses and were soon at their side. This checked the foremost Indians for an instant and saved our two comrades. Although in close range, the Indians did not fire on us when we hastened to the relief of these two men, and why they withheld their fire has always been a mystery I could never solve. There were at the lowest estimate, two hundred of them, well mounted, while we were but four, and they could have easily dispatched us before our comrades could have reached us, and right here I want to say that during the Civil War, then but recently closed, I had participated in fifty-two battles and had served under some of the most skillful cavalry officers in the Confederate army east of the Mississippi, but I had never seen a commander handle his troops with the judgment and skill displayed by a Kiowa chief on that fateful occasion.

“During this hard fought battle, which lasted the rest of the day — say from 11 0'clock until after dark — that chief's maneuvers were in full view and his tactics won the admiration of every ex-Confederate soldier in our little band. Altho' within easy hearing distance, we never heard him give a word of command. A motion of the hand, the pointing of his long lance, or the flourish of his highly decorated shield, seemed to be as clearly understood by his warriors as his words of command could possibly have been. He was decked out in all the paraphernalia of savage warfare, was mounted on a superb bay gelding and seemed to rank the Comanche chief whose costume was less ostentatious and who bestrode a very fine gray.

"Instead of firing on us when we reached Holly and Greenwood, this Kiowa chief seemed to hold up, giving us time to rejoin our comrades who had started back to our relief, and when we had rallied and had made ready to give them a hot reception, he led his men in single file and in perfect order past us, and when he reached a point due west of us and with the utmost coolness and precision formed his men — fully one hundred — in a hollow square. At the same time, and while this movement was in progress, the Comanche chief with about the same number of warriors, led his men back a short distance and drew up in line, their intention, evidently, being to cut us off from the Concho, which was not very distant, and as we soon realized, afforded our only means of defense and ultimate escape, as we were outnumbered more than twelve to one.

"When the Kiowas formed their hollow square they advanced and opened a heavy fire, or more properly speaking, a heavy discharge of arrows, as only a few of them had guns. I counted only four guns in the entire outfit but several had pistols and nearly or quite all carried lances. Each of our men was armed with either an Enfield or Spencer rifle and carried from one to two six shooters and when the Kiowas advanced within our reach, we began to empty their old saddles, but the Kiowa chief held his men steady in line, at the same time employing his shield to ward off the many shots we fired at him.

“‘Shoot that chief!' came from every man in our party, but he seemed invulnerable behind that shield. Captain Schnively lost his head and ordered us to dismount and fight on foot, but some of the men cursed him for being a fool. Col. Dalrymple ordered ten of the men to hold the pack animals, and five others to charge through the Indians who were between us and the Concho. [He] shouted to the boys: 'Stay on your horses boys, draw your pistols and we'll charge 'em!' and with a yell he himself lead the charge we went right in among them, shooting right and left, and they broke. As we sallied in among them, Tom Jones' horse was killed and he fell. Jones recovered his feet bravely in time to parry the thrust of a lance in the hands of an Indian mounted on a splendid horse. Seizing the bridle reins Jones shot the Indian and mounted his horse.

"When we made this charge we had to leave our pack animals for the time being without protection, seeing which the Comanches made an effort to capture them but when they saw their allies, the Kiowas repulsed, they swung round and joined forces. This enabled them to rally and to once more present a bold front. Seeing that our stock were scattering and were liable to capture and that there was a possibility of getting them to the creek, Col. Dalrymple ordered me and my brother to round them up and try to get them to the creek and then turning to the men he said: 'Boys, the scoundrels ain't whipped yet; We '11 have to go right in among them again, and the pick of the herd and one hundred dollars in gold to the man that gets their chief!' The Colonel led the charge, but they held their ground with dogged determination. Several of our horses were killed and more than half our men were wounded more or less severely in this hand-to-hand struggle.

“Col. Dalrymple received a lance thrust through the fleshy part of the arm just below the shoulder, and when the Indian attempted to withdraw it, the barbs of the blade caught in the tendons and muscles of the arm and held fast. Warren Hunter, seeing the Indian tugging at the lance, shot him and his horse having been killed he seized and mounted the fallen Indian's horse. When we, my brother and I, saw the desperate mix-up and that it was going hard with the boys, we abandoned the pack animals and hastened to their relief. Our comrades were gradually yielding, that is giving back, and the Indians were slowly closing round them. They tried to cut us off but we went in with a whoop.

“The boys were somewhat scattered, every man fighting on his own hook. Col.

Dalrymple was holding his own, although encumbered with that lance which was still hanging to his arm. His family still hold it as a relic of the event. When we left the pack animals and started to his relief, and failing to head us off, six Indians got in between us and Dalrymple, thus cutting him off. By this-time his gun and pistols were empty and his only hope was in tail running. He made a break with the lance dangling from his arm, and the six Indians close in after him, my brother and I following right on their heels shooting and yelling. This race was continued for about three hundred yards when the Indians finding themselves going too far from the main body and our fire getting too hot for them, gave up the pursuit and making a circuitous run, rejoined their comrades. Here we found a rallying point for our hard-pressed men and around which the boys soon gathered. It chanced to be near the creek or river which after all was no other than a small stream at this point. The boys fell back to this point fighting, and when we had all collected, the Indians made another charge but were repulsed. As they fell back they rounded up our pack animals, thus capturing all our packs and provisions. In this charge they wounded my horse, rendering him unfit for further service.

“When the Indians fell back, we felt that the worst was yet to come, we had killed and wounded a large number of their warriors and several of their horses and being desperate over their losses and having us at all disadvantages, doubtless they would never give up the contest so long as one of us survived. We improved the time allowed us in preparing for the final struggle which every one of us believed was near at hand. We assisted Colonel Dalrymple from his horse, (he was a large, fleshy man), released the lance from his arm and bound the wound with a handkerchief. He begged for water and I went to the creek near by and brought water in my hat, of which he drank copiously. By this time Tom Jones had found a more secure place, a little ravine or gully that entered the Concho, and to this point we hastened. The banks were very low and while they afforded little protection it was safer there than out in the open. Our pack mules were all killed while on the retreat, and the packs, which contained the bulk of our ammunition and all of our food, were captured. While all this was going on in our locality, the Indians dismounted a number of their bucks and placed them on a high bluff on the opposite side of the creek and overlooking our position, while another party occupied the bed of the creek in our front. Those on the bluff were about 150 yards from us and while they were getting in position several of them bit the dust and we could see their comrades dragging them to the rear just beyond the crest of the bluff. I had cautioned the boys lying close to me to never shoot at a shield as it would be a useless waste of ammunition, but to always take aim at the hips, the legs or the lower part of the abdomen, just below the lower rim of the shield.

Old George Carons was eighty or ninety years of age and bald-headed, and the Indians apparently respected his age and his baldness; otherwise they would have killed him, as he was the last to reach the place of refuge. In the charge he dismounted and case leading his horse as though nothing unusual was happening. Colonel Dalrymple also led his horse in.

“In our first charge we had killed the Kiowa chief's fine horse and now, mounted on another steed we saw him marshalling his braves and by this we knew they were preparing for another desperate charge. Col. Dalrymple had somewhat regained his fighting strength and said to us: 'Boys they are going to come at us again. You fellows be good and ready, keep cool, lay low, select your Indian as they come up, hold a bead on him, and don't fire until I give the word and then if they don't stop let every man rise and with back-to-back we'll sell out.' Colonel Dalrymple, because of his wound, could not use his right arm. With fierce yells and the shaking of shields and lances the Indians came down in a furious charge and it seemed to me that Dalrymple would allow the Indians to ride right over us before giving the order to fire and thinking that an arrow may have knocked him out, I glanced over my shoulder to see what had become of him. I saw that he was all right and had just got my bead on one of the charging rascals and when they were within thirty feet of us, Col. Dalrymple yelled 'Fire!' and from the confused mix-up that followed the roar of our guns, 1 think every man in our outfit emptied a saddle. Some of the riderless horses actually ran over some of our men, who had risen to a stooping posture after the first fire, and were still pumping lead into the fleeing savages, most of whom milled around long enough to recover a few of their dead and wounded. Our deadly fire had completely staggered them for the time being, but after a short respite they rallied and came again and met with a second repulse which was more serious, apparently, than the first. The Kiowa chief rallied his men for the third and last final charge. They were in full view and we watched the chief while he rode up and down his line. Owing to the distance we could not hear his voice but could see his vehement gestures, all that indicated that he was delivering to his braves one of his most eloquent exhortations.

"During all this time we were not idle, but rather making every preparation for the onslaught. The first excitement of battle that too often addles men's heads and in which they become unnerved, had worn off and each man was cool and confident, although suffering from wounds more or less severe and each member of the party was being tortured with a consuming thirst for water, yet, we were sure of whipping the red scoundrels. And here, even in this dire extremity and in the face of impending death, the humorous Jest was not lacking. We saw the chief suddenly wheel and lead off, his men following, but when they reached a point one hundred yards from us, every Indian turned tail, threw his shield over his back, and sped away as if the devil himself were at his heels reaching for his topknot. Finding himself alone, the chief shook his lance defiantly at us, cursed us in Spanish as 'cabrones,' and 'hijos del Diablo,' then wheeling his horse he lit out after his skeedadling braves.

After we had taken our stand in the revine the Indians, failing to rout us, commenced killing our horses, piling them around us on every side, and at the same time making for us very good breastworks.

"During these three charges, those who occupied the bluff, annoyed us incessantly. One of them had an Enfield rifle and nearly every shot brought down one of our horses. To silence this fellow was of the utmost importance, and we didn't have to wait very long for the coveted opportunity.

"When the third charge was repulsed the enemy changed tactics. Those in front retired beyond view and later, numbers of them were seen gathering with them on the bluff, while still others, who had dismounted, were attempting to crawl upon us through the tall grass. Several of their dead still lay in the grass in our front and these they wanted to recover either by stealth or strategy. They crept uncomfortably close to us but not one of them dared show his head. They discharged arrows almost straight up in the air so that in their decent they might strike some of us, point foremost. For a short time the air was filled with these missiles, but owing to a high wind that blew out of the northwest, they were deflected and carried beyond their intended mark, although many of them fell near us, some coming down with a force that broke the shaft. This unusual target practice lasted nearly an hour. While this 'sky shooting' was in progress some of the men saw the grass moving against the wind in our front. Evidently an Indian was crawling up to tie a rope about the body of a dead comrade that lay where he fell, and a close watch was kept on that particular point. Presently a feather was seen bobbing up and down and a little later a black head was raised as if to get his bearings. There was a shot — and another dead Indian.

“The Indian with the Enfield on the bluff was next disposed of. He was perched behind a rock or boulder on the brink of the elevation and we had wasted a lot of lead trying to put him out of business. I had tried to pick him off several times and had failed, but finally I got the distance down fine and drew a bead on the little opening by the boulder where he stuck his head when he rose to fire, and when his black noggin darkened this opening, I let drive and knocked the whole top of his head off. When the ball struck him he made a wild leap, fell over the ledge and rolled to the base of the bluff. This silenced the long range Enfield, but not until about all our horses were killed.

== End of Part One ==

~The Old Bookaroo

Last edited: