Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,475

- 3,801

This one is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Don Jose de La Mancha, Real de Tayopa Tropical Tramp, our missing companero. He always enjoyed these Sunday stories. Hoist up a mug of coffee - sock, boiled, ground or instant, with or without eggshells or a horseshoe - to his memory.

And take this yarn, like your cup of Arbuckle Mud, with a pinch of salt.

Superstition Mine

By SCUDDER MARTIN

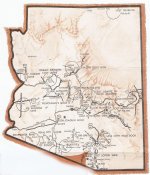

THE Apache Trail in Arizona, traversed daily by tourists, leads directly past the eerie region of Superstition Mountain. Among the earliest prospectors there was dread of this mountain although it was known to be rich in ores. Indians had told the story that no man who ventured there ever came out alive. However that may be, there was a man, a Mexican –though it was said he had spent his earlier years in an Apache lodge–who ventured there many times.

Jose Varelli knew many things which no one but the Indians could have told him. He knew the traditions of the redmen, the location of their dwellings, their history of warfare, their sources of food, where and how they buried their dead, where were their strongholds and their council-places, and last but by no means least, all their stories of lost mines of the country far and wide.

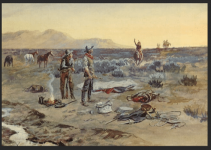

White men of all creeds came and went, but the Mexican, Jose Varelli, was well known in the camps where he came at intervals to get fresh supplies. With a new grub-stake he would set out again to search for one of the fabled lost veins of wealth in old Superstition Mountain. It was the day of the cowboy, the stage coach, the prospector, the criminal. Bands of outlaws roaming the West made this country a place of terror to traveler and settler alike. More to be feared than the Indians, they robbed and murdered without warning or reason, while the movements of the redskins could often be anticipated and safety sought.

Gregg's saloon in Florence, one of the places where Jose was generally found when not in the hills, saw all white men sooner or later. It was at Gregg's that some of the daring raids were planned, and Gregg's itself witnessed several of the boldest hold-ups of the early frontier, including the one in which that notorious outlaw, Gene Hunter, got away with the eighteen-thousand-dollar bag of nuggets which was to have ransomed Kit Carson, had fortune not miscarried. As it was, the ransom had to be made up again; and later it was proven that both amounts went to the same gang of criminals.

One day in early August Jose Varelli dropped into Florence and soon found his way to Gregg's. He had with him a bag of funny black rocks. Immediately he drew the crowd of idlers about him by his story of a wonderful find he had made–“somewhere.” He would say no more than that–“somewhere,” with his smile. He was not too elated to remain the same good old Jose that Florence had known for a decade. It was probably this fact that insured him a respectful audience among the usual crowd of loafers at Gregg's. But among them were two, Cass Bird and Dick King, who were new arrivels [sic] in Florence and who were not there for any good purpose. They missed no detail. Jose should have the “capital” necessary to develop his mine as he wished; while they–well, leave that till later.

Before ten o'clock that night Bird and King had their plans made. King put his proposition to Jose along with a great deal of bad liquor. Jose entrusted to this good stranger a fund of information. The mine was a lost mine of his Indian friends; there were traces of early workings. Certainly Jose had papers regarding it –yes, maps and other necessary papers the priest had arranged for him that day. But were they in a safe place? “Si señor;” the señor could see for himself, here, inside and lining Jose's coat—stitches.

“Bueño,” said King and asked if he might let a friend of his, a mining engineer come with them to see the property?

By this time, as can be imagined, Jose was losing his caution in a wave of good comradeship, and consented to set forth at once.

It was only a two days’ journey. Supplies he could get in an hour, in fact did get, in spite of his drunkenness. The “mining engineer,” Mr. Bird, joined them.

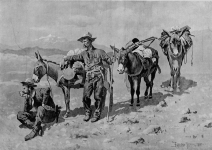

An hour before daylight they started, three men and two burros. By the first streak of day they were out in the desert with low hills to break the monotony of brush and sand.

A day's travel through the heat led them along a shallow stream of clear water, now above ground, now below. It wound around hills or slipped down some box canyon to more level land. Jose said little to his companions, but prodded the burros. King and Bird followed with few spoken words. The journey was not pleasant to them except as it led to treasure.

Jose had some of the characteristics of the redman; he was shrewd when suspicious. For all his silence, and his moments of irresponsibility whenever he approached civilization's habitat, he had an alert mind. During the entire journey he had been busy turning the offer of the strangers over in his mind. He was more nearly sober now, and the proposition seemed different in the broad glare of day. Their offers to finance him had been too good.

When camp was made and darkness stole over the purple hills, Jose was already cursing himself for a fool.

The night, like some nights on the desert, brought no relief from the heat of the day. The wind, scorchingly hot, blew lightly with an electric quality that fanned the cheek with out a comforting touch. The men spread blankets on which to lie to protect themselves from the hot sands and the sting of the cactus thorns. Jose fell into a peaceful rest, perhaps only half slumbering, yet refreshing, but for hours his companions tossed before weariness overcame them.

The Mexican arose with the break of day and was preparing the breakfast fare almost before his unwelcome guests had rubbed their sleepy eyes and stretched their aching limbs. Another day of it and they would know the location of the bonanza. Also, thought Bird and King, they would secure the papers Jose kept so close to his bosom. Then with Jose's guidance they would return to Florence. Jose, that is, would guide them–part way.

In the afternoon the canteens were empty. Water is the gold of the desert without which life itself is naught. But the prospector knew where to get water. He would go while they rested. The country was now rugged with the barrenness of rock showing little vegetation except for varieties of cacti, and sage in clumps. The caravan had climbed steadily and it was a bit cooler for them.

Jose set off with the canteens and in an hour and three quarters was returning. But he did not journey directly toward camp. His attention had been drawn to a freshly made trail. Following it a short distance he observed it had been made by a number of horsemen. Whether friend or foe, Indian or white, bandit or traveler, he could not tell. There appeared to have been three or four horses. Further examination led Jose to fear that Indians were abroad, and to no white man's good.

Having been the ward of Indians in his youth, Jose felt no fear for himself, but the two men he had guided into this country were in danger. To hide them until this danger passed would be wise. Although American troops were stationed at Picket Post and patroled [sic] the surrounding territory constantly, yet there was no place of safety near at hand.

The mine! That was a place impregnable and unknown. Jose hesitated not a moment but hurried to the camp to appraise the two men of his knowledge. He found them rested and willing to go wherever he led.

The two men and their guide made all haste possible to complete their travel to the mine. They were cautious through common danger, and fear urged their strength until the miles to safety sped by.

King and Bird did not know of the mine in their approach, so completely was the entrance screened by sage brush and rocks piled there by Nature herself. Jose led the way into a large cavern which seemed to stretch back and down, they could not see where. The walls dripped a saline moisture and in the refreshing coolness the three men sank down exhausted.

In neat piles on the floor, and near the entrance, could be seen in the dim light rocks heavy with ore; as though some careful hand had been at work in this unknown sepulcher. It was, in fact the result of Jose's work on his previous trip. Thus had he gauged and tested his discovery, hardly convinced by casual observation, and finding it almost impossible to believe in the richness of his find.

Surrounded by wealth, the two adventurers whose lives were in Jose's hands, now had no thought of money. Cringing in the darkness they longed for the safety of home, or the chances of the gaming table, rather than the precarious chance of the mine. Forgetting to feel gratitude; forgetting to gloat over their discovered wealth; forgetting to exercise their planned power over Jose;–these two could think now only of escape from the menace of torture by the redmen, or death by starvation. They were surly and quarrelsome and full of fear for themselves when they spoke at all.

Jose bore patiently all their harsh words and rationed their water and supplies as best he could. From a cleft in their fortress they had a view over considerable territory. They had been confined two days when they observed two bands of Indians pass. Safe for the present in their treasure house, they could picture the smoking ruins of homes in isolated places in the path of the redskins, for when the savages got beyond bounds there was desolation in their wake.

Chafing under confinement and terrorized through fear of thirst and starvation, King and Bird were emboldened to the point of risking a return to Florence, although Jose cautioned them to wait longer. It was decided Jose should seek to reach a water supply, fill the canteens, and upon his return report on the safety of venturing forth. Should he be intercepted he must use strategy in order not to disclose the presence of his companions. Probably Jose would find friends among the marauders.

The third night, clutching two canteens and urged by the men, Jose crept cautiously out of the mine and into the darkness.

The terror of that night for Bird and King was lightened by their hopes of a return to Florence, with their knowledge of the mine; for with the return of hope, they were again plotting. Again they were plunged into the depths of despair by the failure of Jose to return, and they began to fear he would not come at all.

When the Mexican did return at break of day he stumbled in with the full canteens and fell at their feet. His coat was gone; he could not speak coherently. He was disheveled and babbling. The white men knew not what had occurred on his trip but they administered to him in hopes that he might be able to tell them.

Throughout the day Jose raved, delirious with fever. He was very ill and before nightfall a dread worse than fear came to the watchers. The plague! that terrible reaper of white and Indian was in their midst–smallpox was claiming another victim. In panic the men crept out into the dusk of evening, not neglecting to take the canteens. In his delirium Jose did not know of their treachery.

Skulking like animals the partners in crime hurried and scurried until far from the scene. Fearing foes, they sneaked across the landscape from bush to bush in the moonlight. Nearly exhausted, they slept when daylight overtook them, but pressed on when their strength returned. Together they sought the direction of Florence, and together they wandered far from what they sought.

Any desert traveller[sic] knows the peril of the stranger on an arid waste. It is needless to recount the sufferings he may encounter.

The mail stage into Florence picked up one of these two, King it proved to be, and carried him to Florence. His tongue was swollen black and his throat was so dry with thirst that only sops of water could be given or he would have gone mad with desire to drink–drink.

When he recovered a little, King told how, with his companion, he had stripped cactus thorns with bare hands and drunk of the sap within, to sustain life another day. He told how he had seen Bird, his companion, go raving crazy and lick the blood from feet and hands ... too horrible! How Bird died…in agony.

The survivor did not tell the story of Jose; instead he tried to forget. But stories of Superstition Mountain made him cringe with that nameless fear of retribution at his heels.

The trouble with the Indians was not yet settled, although the soldiers at Picket Post had things well in hand. They sent out relays of brave men to encounter the raiders. Skirmishes were light as the Indians scattered into small bands–their custom when pursued, banding together again for raids to massacre some colony or wagon train.

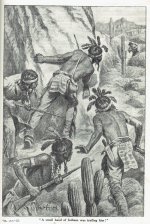

When King got well he was asked to accompany a band of six or eight men on a search for the body of Bird that they might bury him as befitted a white man. Buzzards and coyotes and savages would not let a man's soul rest with bones above ground. At any time the red skins might again break forth, for they were by no means subdued.

King dared not refuse to lead the men, but he felt that same dread at his heels. Was there retribution, or was it imagination coupled with memory? Led to the spot where Bird succumbed, the party was taken wholly by surprise to find themselves ambushed by Indians. Some thirty surrounded them and a brisk battle followed. King was carried off alive and the Indians immediately withdrew. Pursuit was futile without reinforcements; rescue of King impossible. When soldiers were able to take the trail it was too late to encounter the kidnappers.

About this time the raids of the Indians ceased. Possibly the main cause was a mysterious epidemic which largely reduced their numbers. At any rate their depredations came to an end. News of Jose Varelli, or his murderers, never came to camp. The kidnapping of King was unexplained. Whether he met death by slow torture or by disease is conjecture. However, Superstition Mountain has whispered another eerie chapter to the story:

Late in the winter of 1921 a game hunter in the Superstition Range of Arizona reported finding a cavern filled with the bones of human beings. A coroner's jury investigated. There were bones of young and old, men and women, not buried but lying in positions indicating natural death. It was thought that the cavern might have been used as a pest-house by an Indian tribe.

But among the skeletons were two somewhat different. One of these seemed to be that of a large white man, the other was, evidently, not Indian. On the floor were piles of rocks, seemingly ore, gathered long ago, piled in systematic manner. But the cavern was a sepulcher of the dead and told no tales.

Superstition Mountain can only whisper the solution.

Editor’s Note: I found a reference to this piece in the Western Treasures’ Ghost Town Guide (1973) — not an easy thing to do, because the table of contents has the wrong page number. Happily, Probert has the correct reference for the “Tayopa-Lost Dutchman Research Sources!” (pg. 25).

Is this a work of fact or fiction, or a blend of both?

That is up to the reader to decide - ¿Quien Sabe?

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

And take this yarn, like your cup of Arbuckle Mud, with a pinch of salt.

Superstition Mine

By SCUDDER MARTIN

THE Apache Trail in Arizona, traversed daily by tourists, leads directly past the eerie region of Superstition Mountain. Among the earliest prospectors there was dread of this mountain although it was known to be rich in ores. Indians had told the story that no man who ventured there ever came out alive. However that may be, there was a man, a Mexican –though it was said he had spent his earlier years in an Apache lodge–who ventured there many times.

Jose Varelli knew many things which no one but the Indians could have told him. He knew the traditions of the redmen, the location of their dwellings, their history of warfare, their sources of food, where and how they buried their dead, where were their strongholds and their council-places, and last but by no means least, all their stories of lost mines of the country far and wide.

White men of all creeds came and went, but the Mexican, Jose Varelli, was well known in the camps where he came at intervals to get fresh supplies. With a new grub-stake he would set out again to search for one of the fabled lost veins of wealth in old Superstition Mountain. It was the day of the cowboy, the stage coach, the prospector, the criminal. Bands of outlaws roaming the West made this country a place of terror to traveler and settler alike. More to be feared than the Indians, they robbed and murdered without warning or reason, while the movements of the redskins could often be anticipated and safety sought.

Gregg's saloon in Florence, one of the places where Jose was generally found when not in the hills, saw all white men sooner or later. It was at Gregg's that some of the daring raids were planned, and Gregg's itself witnessed several of the boldest hold-ups of the early frontier, including the one in which that notorious outlaw, Gene Hunter, got away with the eighteen-thousand-dollar bag of nuggets which was to have ransomed Kit Carson, had fortune not miscarried. As it was, the ransom had to be made up again; and later it was proven that both amounts went to the same gang of criminals.

One day in early August Jose Varelli dropped into Florence and soon found his way to Gregg's. He had with him a bag of funny black rocks. Immediately he drew the crowd of idlers about him by his story of a wonderful find he had made–“somewhere.” He would say no more than that–“somewhere,” with his smile. He was not too elated to remain the same good old Jose that Florence had known for a decade. It was probably this fact that insured him a respectful audience among the usual crowd of loafers at Gregg's. But among them were two, Cass Bird and Dick King, who were new arrivels [sic] in Florence and who were not there for any good purpose. They missed no detail. Jose should have the “capital” necessary to develop his mine as he wished; while they–well, leave that till later.

Before ten o'clock that night Bird and King had their plans made. King put his proposition to Jose along with a great deal of bad liquor. Jose entrusted to this good stranger a fund of information. The mine was a lost mine of his Indian friends; there were traces of early workings. Certainly Jose had papers regarding it –yes, maps and other necessary papers the priest had arranged for him that day. But were they in a safe place? “Si señor;” the señor could see for himself, here, inside and lining Jose's coat—stitches.

“Bueño,” said King and asked if he might let a friend of his, a mining engineer come with them to see the property?

By this time, as can be imagined, Jose was losing his caution in a wave of good comradeship, and consented to set forth at once.

It was only a two days’ journey. Supplies he could get in an hour, in fact did get, in spite of his drunkenness. The “mining engineer,” Mr. Bird, joined them.

An hour before daylight they started, three men and two burros. By the first streak of day they were out in the desert with low hills to break the monotony of brush and sand.

A day's travel through the heat led them along a shallow stream of clear water, now above ground, now below. It wound around hills or slipped down some box canyon to more level land. Jose said little to his companions, but prodded the burros. King and Bird followed with few spoken words. The journey was not pleasant to them except as it led to treasure.

Jose had some of the characteristics of the redman; he was shrewd when suspicious. For all his silence, and his moments of irresponsibility whenever he approached civilization's habitat, he had an alert mind. During the entire journey he had been busy turning the offer of the strangers over in his mind. He was more nearly sober now, and the proposition seemed different in the broad glare of day. Their offers to finance him had been too good.

When camp was made and darkness stole over the purple hills, Jose was already cursing himself for a fool.

The night, like some nights on the desert, brought no relief from the heat of the day. The wind, scorchingly hot, blew lightly with an electric quality that fanned the cheek with out a comforting touch. The men spread blankets on which to lie to protect themselves from the hot sands and the sting of the cactus thorns. Jose fell into a peaceful rest, perhaps only half slumbering, yet refreshing, but for hours his companions tossed before weariness overcame them.

The Mexican arose with the break of day and was preparing the breakfast fare almost before his unwelcome guests had rubbed their sleepy eyes and stretched their aching limbs. Another day of it and they would know the location of the bonanza. Also, thought Bird and King, they would secure the papers Jose kept so close to his bosom. Then with Jose's guidance they would return to Florence. Jose, that is, would guide them–part way.

In the afternoon the canteens were empty. Water is the gold of the desert without which life itself is naught. But the prospector knew where to get water. He would go while they rested. The country was now rugged with the barrenness of rock showing little vegetation except for varieties of cacti, and sage in clumps. The caravan had climbed steadily and it was a bit cooler for them.

Jose set off with the canteens and in an hour and three quarters was returning. But he did not journey directly toward camp. His attention had been drawn to a freshly made trail. Following it a short distance he observed it had been made by a number of horsemen. Whether friend or foe, Indian or white, bandit or traveler, he could not tell. There appeared to have been three or four horses. Further examination led Jose to fear that Indians were abroad, and to no white man's good.

Having been the ward of Indians in his youth, Jose felt no fear for himself, but the two men he had guided into this country were in danger. To hide them until this danger passed would be wise. Although American troops were stationed at Picket Post and patroled [sic] the surrounding territory constantly, yet there was no place of safety near at hand.

The mine! That was a place impregnable and unknown. Jose hesitated not a moment but hurried to the camp to appraise the two men of his knowledge. He found them rested and willing to go wherever he led.

The two men and their guide made all haste possible to complete their travel to the mine. They were cautious through common danger, and fear urged their strength until the miles to safety sped by.

King and Bird did not know of the mine in their approach, so completely was the entrance screened by sage brush and rocks piled there by Nature herself. Jose led the way into a large cavern which seemed to stretch back and down, they could not see where. The walls dripped a saline moisture and in the refreshing coolness the three men sank down exhausted.

In neat piles on the floor, and near the entrance, could be seen in the dim light rocks heavy with ore; as though some careful hand had been at work in this unknown sepulcher. It was, in fact the result of Jose's work on his previous trip. Thus had he gauged and tested his discovery, hardly convinced by casual observation, and finding it almost impossible to believe in the richness of his find.

Surrounded by wealth, the two adventurers whose lives were in Jose's hands, now had no thought of money. Cringing in the darkness they longed for the safety of home, or the chances of the gaming table, rather than the precarious chance of the mine. Forgetting to feel gratitude; forgetting to gloat over their discovered wealth; forgetting to exercise their planned power over Jose;–these two could think now only of escape from the menace of torture by the redmen, or death by starvation. They were surly and quarrelsome and full of fear for themselves when they spoke at all.

Jose bore patiently all their harsh words and rationed their water and supplies as best he could. From a cleft in their fortress they had a view over considerable territory. They had been confined two days when they observed two bands of Indians pass. Safe for the present in their treasure house, they could picture the smoking ruins of homes in isolated places in the path of the redskins, for when the savages got beyond bounds there was desolation in their wake.

Chafing under confinement and terrorized through fear of thirst and starvation, King and Bird were emboldened to the point of risking a return to Florence, although Jose cautioned them to wait longer. It was decided Jose should seek to reach a water supply, fill the canteens, and upon his return report on the safety of venturing forth. Should he be intercepted he must use strategy in order not to disclose the presence of his companions. Probably Jose would find friends among the marauders.

The third night, clutching two canteens and urged by the men, Jose crept cautiously out of the mine and into the darkness.

The terror of that night for Bird and King was lightened by their hopes of a return to Florence, with their knowledge of the mine; for with the return of hope, they were again plotting. Again they were plunged into the depths of despair by the failure of Jose to return, and they began to fear he would not come at all.

When the Mexican did return at break of day he stumbled in with the full canteens and fell at their feet. His coat was gone; he could not speak coherently. He was disheveled and babbling. The white men knew not what had occurred on his trip but they administered to him in hopes that he might be able to tell them.

Throughout the day Jose raved, delirious with fever. He was very ill and before nightfall a dread worse than fear came to the watchers. The plague! that terrible reaper of white and Indian was in their midst–smallpox was claiming another victim. In panic the men crept out into the dusk of evening, not neglecting to take the canteens. In his delirium Jose did not know of their treachery.

Skulking like animals the partners in crime hurried and scurried until far from the scene. Fearing foes, they sneaked across the landscape from bush to bush in the moonlight. Nearly exhausted, they slept when daylight overtook them, but pressed on when their strength returned. Together they sought the direction of Florence, and together they wandered far from what they sought.

Any desert traveller[sic] knows the peril of the stranger on an arid waste. It is needless to recount the sufferings he may encounter.

The mail stage into Florence picked up one of these two, King it proved to be, and carried him to Florence. His tongue was swollen black and his throat was so dry with thirst that only sops of water could be given or he would have gone mad with desire to drink–drink.

When he recovered a little, King told how, with his companion, he had stripped cactus thorns with bare hands and drunk of the sap within, to sustain life another day. He told how he had seen Bird, his companion, go raving crazy and lick the blood from feet and hands ... too horrible! How Bird died…in agony.

The survivor did not tell the story of Jose; instead he tried to forget. But stories of Superstition Mountain made him cringe with that nameless fear of retribution at his heels.

The trouble with the Indians was not yet settled, although the soldiers at Picket Post had things well in hand. They sent out relays of brave men to encounter the raiders. Skirmishes were light as the Indians scattered into small bands–their custom when pursued, banding together again for raids to massacre some colony or wagon train.

When King got well he was asked to accompany a band of six or eight men on a search for the body of Bird that they might bury him as befitted a white man. Buzzards and coyotes and savages would not let a man's soul rest with bones above ground. At any time the red skins might again break forth, for they were by no means subdued.

King dared not refuse to lead the men, but he felt that same dread at his heels. Was there retribution, or was it imagination coupled with memory? Led to the spot where Bird succumbed, the party was taken wholly by surprise to find themselves ambushed by Indians. Some thirty surrounded them and a brisk battle followed. King was carried off alive and the Indians immediately withdrew. Pursuit was futile without reinforcements; rescue of King impossible. When soldiers were able to take the trail it was too late to encounter the kidnappers.

About this time the raids of the Indians ceased. Possibly the main cause was a mysterious epidemic which largely reduced their numbers. At any rate their depredations came to an end. News of Jose Varelli, or his murderers, never came to camp. The kidnapping of King was unexplained. Whether he met death by slow torture or by disease is conjecture. However, Superstition Mountain has whispered another eerie chapter to the story:

Late in the winter of 1921 a game hunter in the Superstition Range of Arizona reported finding a cavern filled with the bones of human beings. A coroner's jury investigated. There were bones of young and old, men and women, not buried but lying in positions indicating natural death. It was thought that the cavern might have been used as a pest-house by an Indian tribe.

But among the skeletons were two somewhat different. One of these seemed to be that of a large white man, the other was, evidently, not Indian. On the floor were piles of rocks, seemingly ore, gathered long ago, piled in systematic manner. But the cavern was a sepulcher of the dead and told no tales.

Superstition Mountain can only whisper the solution.

----- o0o -----

Editor’s Note: I found a reference to this piece in the Western Treasures’ Ghost Town Guide (1973) — not an easy thing to do, because the table of contents has the wrong page number. Happily, Probert has the correct reference for the “Tayopa-Lost Dutchman Research Sources!” (pg. 25).

Is this a work of fact or fiction, or a blend of both?

That is up to the reader to decide - ¿Quien Sabe?

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

Amazon Forum Fav 👍

Last edited: