Gypsy Heart

Gold Member

I think this would be a fantastic place to hunt if permission could be obtained....

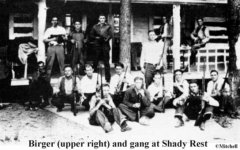

Shady Rest opened for business in 1924 and offered bootleg, gambling cockfights and dog fights. During the day, things stayed pretty quiet, catering mostly to liquor runners who would make the last leg of their trip to St. Louis after dark. Although notorious all over southern Illinois, no police officials ever raided or bothered the place. It was no secret what it was bring used for or that it had been built to withstand a siege if necessary. The building had been constructed with foot-thick log walls and a deep basement. Rifles, sub-machine guns and boxes of ammunition lined the walls, alongside canned food and water. Floodlights, supplied with electricity that was generated on the grounds, prevented anyone from sneaking up on Shady Rest in the night.

The place became very popular with the locals until early 1926, when the relationship between Birger and the Sheltons fell apart. After that, the bloody climate of the location kept many customers away. Regardless, a number of people in the area still chose to see Charlie Birger as a public benefactor rather than as a killer and bootlegger. My friend Bernie Bernard, who grew up in the area, told me that his grandfather fondly recalled buying barbeque from the stand at Shady Rest and often selling milk and eggs to Birger, who he remarked was a “kind and very polite man”. In addition, accounts have it that Birger once gave coal to all of the destitute families in Harrisburg during one bitterly cold winter. He also allegedly provided school books for children and vowed that he would not let Harrisburg residents play at his gambling tables. He had no desire, he claimed, to take their money.

Why the bloody rift developed between Birger and the Sheltons is unclear. Most likely, it was simply business that became personal. The two groups had originally united to fight back against Young and the Klan’s encroachment on their business. Once the Klan was wiped out, there was no one left to fight but each other. Regardless of why it started though, it plunged southern Illinois once more into chaos. The war began in 1926 and small towns, farms and road houses in the region were terrorized as both sides built armed vehicles to carry out deadly reprisals against one another. Machine guns blasted, speakeasys were torn apart with gunfire and many died during the fighting.

In November 1926, a Birger associate named Milroy was gunned down as he left a roadhouse in the town of Colp. The mayor and the chief of police, called in from another roadhouse nearby, were shot at from the darkness as they got out of their car. The mayor was fatally wounded but the police chief managed to escape with a shattered hand. Both men, it was said, were enemies of the Sheltons.

A few days later, a homemade bomb was tossed from a speeding car towards Shady Rest. The bomb had been intended for the barbeque stand, but it had missed and Birger’s hideout was unharmed. Two days later, machine gunner‘s (allegedly sent by Birger) shot up the home of Joe Adams, the mayor of West City. He was a friend of the Sheltons and a mechanic who often did work on the armored vehicle they had built.

Then, hours later, the only bombs dropped in aerial warfare in America fell on Shady Rest. In full daylight, an airplane flew low over Birger’s hideout as his men watched. A few bundles were thrown from the cockpit, which turned out to be dynamite bound around bottle of nitroglycerine. The “bombs” were so poorly constructed that they never exploded. The following week, a more effective bomb was thrown in response, this time by the Birger gang. It exploded in front of Adams’ house, damaging the front porch, blowing the door off its hinges, and shattering the windows. No one was injured, but not for long.

On December 12, two men came to the door of Mayor Joe Adams’ and told his wife they had a letter from Carl Shelton. When he answered his wife’s call, one of the men handed Adams a note. While he read it, both of them pulled guns from the coats and shot the man in the chest. He lived just long enough to tell his wife that he hadn’t recognized the killers. She blamed the killing on Charlie Birger.

The gang war soon reached its climax. Around midnight on January 9, 1927, a farmer who lived a short distance from Shady Rest was awakened by five or six gunshots. They were followed a short time later by a massive explosion that destroyed Shady Rest and shook his own home. The fire burned so hot that no one dared approach the ruined structure until morning. By then, it was merely ashes and burned embers. However, among the remains were four bodies, charred beyond recognition. One of the bodies later turned out to be Elmo Thomasson, a member of the Birger gang.

From all appearances, Birger was finished... but he still managed to beat the Sheltons in the end. Although he had failed to beat his rivals with guns and dynamite, he did manage to beat them by using the US government against them instead. Back in 1925, a post office messenger in Collinsville had been robbed of a mine payroll adding up to around $21,000. The crime had remained unsolved. Birger contacted the postal inspector and managed to convince him that the Sheltons had pulled the job. A federal grand jury indicted the brothers and they were convicted by a jury. The Sheltons were each given 25 years in federal prison but were later given new trials.

After the gang war, the Sheltons never returned to Williamson County. They moved their operations to East St. Louis, continuing with bootlegging, prostitution and gambling until they were driven out of the area. They re-established themselves in the Peoria area, where they continued their activities for many years. Carl was killed there in 1947... Bernie was fatally shot outside his tavern in the summer of 1948... and Earl died peacefully after surviving a murderous attack near Fairfield in 1949.

As for Charlie Birger, he had won the gang war and had put his rivals out of business... but his victory wouldn’t last. Things started to break bad when the police arrested Harry Thomasson on a robbery charge. Franklin County State’s Attorney Roy Martin suspected the man also was involved in the murder of West City's Mayor, Joe Adams. Thomasson was associated with Charlie Birger, but their relationship had been rocky since the burning of Shady Rest. Harry had begun to suspect that Birger himself had been responsible for the bombing of the roadhouse, which had killed his brother Elmo. Looking for a deal, he confessed to the murder of Joe Adams and he implicated Birger in the crime. He explained that he had been paid $150 per shot by Charlie.

This was the beginning of the end. Another Birger gang member, Art Newman, who had once owned the Arlington Hotel in East St. Louis, had fled to California but was captured there and brought back to Illinois on a murder charge. On the trip back, he confessed to taking part in the murder of Lory Price, a state patrol officer who had been a friend of Birger. Witnesses had indicated that Price had been at Shady Rest on the night of the explosion and he and his wife had disappeared mysteriously a short time later. Newman was indicted for the murder, along with Birger and four other gang members. The details of the murder have never been clear, but Price’s body was found in a field by a farmer, while his wife’s corpse was later discovered in an old mine shaft near Johnston City.

Birger was arrested for the murder of Joe Adams on April 29, 1927 and he was tried for murder that summer in Franklin County. In late July, after 24 hours of deliberation, the jury returned with its verdict, finding Birger guilty. He was sentenced to death, although was granted a stay of execution as he appealed the verdict. In late February 1928, the Illinois Supreme Court denied his appeal and sentenced him to die on April 13. Birger claimed to be relieved and said that he would rather die than spend another 10 months in jail.

Another appeal was attempted but turned down on April 12 by the State Board of Pardons and Paroles. After this failure, Birger’s lawyer rushed to Benton and field another petition. This one was in the name of Charlie’s nephew, Nathan Birger, and it asked for a sanity hearing. The execution was postponed again and on April 16, the hearing began. Birger made a desperate attempt to escape death, making a fool of himself by cursing at reporters, cowering and rolling his head from side to side. Spectators in the crowd actually laughed at him and the jury took just 12 minutes to find him totally sane. He was not scheduled to die on April 19.

He would be the last man to die on the gallows in the state of Illinois. During that same month, the Illinois legislature abolished hanging and substituted the electric chair as a humane method of execution in the state.

Thanks to Charlie’s notoriety, a “county fair atmosphere” was used to characterize the town of Benton on the day of the hanging. Thousands of people jammed to streets although only a few hundred of them actually had tickets to the execution.

Birger climbed the steps of the scaffold with a bright smile on his face, laughing and joking with the officials. “It’s a beautiful world,” he grinned and those became the last words of the man who had become a larger-than-life part of Little Egypt. Six minutes later, Charlie Birger was dead.

Shady Rest opened for business in 1924 and offered bootleg, gambling cockfights and dog fights. During the day, things stayed pretty quiet, catering mostly to liquor runners who would make the last leg of their trip to St. Louis after dark. Although notorious all over southern Illinois, no police officials ever raided or bothered the place. It was no secret what it was bring used for or that it had been built to withstand a siege if necessary. The building had been constructed with foot-thick log walls and a deep basement. Rifles, sub-machine guns and boxes of ammunition lined the walls, alongside canned food and water. Floodlights, supplied with electricity that was generated on the grounds, prevented anyone from sneaking up on Shady Rest in the night.

The place became very popular with the locals until early 1926, when the relationship between Birger and the Sheltons fell apart. After that, the bloody climate of the location kept many customers away. Regardless, a number of people in the area still chose to see Charlie Birger as a public benefactor rather than as a killer and bootlegger. My friend Bernie Bernard, who grew up in the area, told me that his grandfather fondly recalled buying barbeque from the stand at Shady Rest and often selling milk and eggs to Birger, who he remarked was a “kind and very polite man”. In addition, accounts have it that Birger once gave coal to all of the destitute families in Harrisburg during one bitterly cold winter. He also allegedly provided school books for children and vowed that he would not let Harrisburg residents play at his gambling tables. He had no desire, he claimed, to take their money.

Why the bloody rift developed between Birger and the Sheltons is unclear. Most likely, it was simply business that became personal. The two groups had originally united to fight back against Young and the Klan’s encroachment on their business. Once the Klan was wiped out, there was no one left to fight but each other. Regardless of why it started though, it plunged southern Illinois once more into chaos. The war began in 1926 and small towns, farms and road houses in the region were terrorized as both sides built armed vehicles to carry out deadly reprisals against one another. Machine guns blasted, speakeasys were torn apart with gunfire and many died during the fighting.

In November 1926, a Birger associate named Milroy was gunned down as he left a roadhouse in the town of Colp. The mayor and the chief of police, called in from another roadhouse nearby, were shot at from the darkness as they got out of their car. The mayor was fatally wounded but the police chief managed to escape with a shattered hand. Both men, it was said, were enemies of the Sheltons.

A few days later, a homemade bomb was tossed from a speeding car towards Shady Rest. The bomb had been intended for the barbeque stand, but it had missed and Birger’s hideout was unharmed. Two days later, machine gunner‘s (allegedly sent by Birger) shot up the home of Joe Adams, the mayor of West City. He was a friend of the Sheltons and a mechanic who often did work on the armored vehicle they had built.

Then, hours later, the only bombs dropped in aerial warfare in America fell on Shady Rest. In full daylight, an airplane flew low over Birger’s hideout as his men watched. A few bundles were thrown from the cockpit, which turned out to be dynamite bound around bottle of nitroglycerine. The “bombs” were so poorly constructed that they never exploded. The following week, a more effective bomb was thrown in response, this time by the Birger gang. It exploded in front of Adams’ house, damaging the front porch, blowing the door off its hinges, and shattering the windows. No one was injured, but not for long.

On December 12, two men came to the door of Mayor Joe Adams’ and told his wife they had a letter from Carl Shelton. When he answered his wife’s call, one of the men handed Adams a note. While he read it, both of them pulled guns from the coats and shot the man in the chest. He lived just long enough to tell his wife that he hadn’t recognized the killers. She blamed the killing on Charlie Birger.

The gang war soon reached its climax. Around midnight on January 9, 1927, a farmer who lived a short distance from Shady Rest was awakened by five or six gunshots. They were followed a short time later by a massive explosion that destroyed Shady Rest and shook his own home. The fire burned so hot that no one dared approach the ruined structure until morning. By then, it was merely ashes and burned embers. However, among the remains were four bodies, charred beyond recognition. One of the bodies later turned out to be Elmo Thomasson, a member of the Birger gang.

From all appearances, Birger was finished... but he still managed to beat the Sheltons in the end. Although he had failed to beat his rivals with guns and dynamite, he did manage to beat them by using the US government against them instead. Back in 1925, a post office messenger in Collinsville had been robbed of a mine payroll adding up to around $21,000. The crime had remained unsolved. Birger contacted the postal inspector and managed to convince him that the Sheltons had pulled the job. A federal grand jury indicted the brothers and they were convicted by a jury. The Sheltons were each given 25 years in federal prison but were later given new trials.

After the gang war, the Sheltons never returned to Williamson County. They moved their operations to East St. Louis, continuing with bootlegging, prostitution and gambling until they were driven out of the area. They re-established themselves in the Peoria area, where they continued their activities for many years. Carl was killed there in 1947... Bernie was fatally shot outside his tavern in the summer of 1948... and Earl died peacefully after surviving a murderous attack near Fairfield in 1949.

As for Charlie Birger, he had won the gang war and had put his rivals out of business... but his victory wouldn’t last. Things started to break bad when the police arrested Harry Thomasson on a robbery charge. Franklin County State’s Attorney Roy Martin suspected the man also was involved in the murder of West City's Mayor, Joe Adams. Thomasson was associated with Charlie Birger, but their relationship had been rocky since the burning of Shady Rest. Harry had begun to suspect that Birger himself had been responsible for the bombing of the roadhouse, which had killed his brother Elmo. Looking for a deal, he confessed to the murder of Joe Adams and he implicated Birger in the crime. He explained that he had been paid $150 per shot by Charlie.

This was the beginning of the end. Another Birger gang member, Art Newman, who had once owned the Arlington Hotel in East St. Louis, had fled to California but was captured there and brought back to Illinois on a murder charge. On the trip back, he confessed to taking part in the murder of Lory Price, a state patrol officer who had been a friend of Birger. Witnesses had indicated that Price had been at Shady Rest on the night of the explosion and he and his wife had disappeared mysteriously a short time later. Newman was indicted for the murder, along with Birger and four other gang members. The details of the murder have never been clear, but Price’s body was found in a field by a farmer, while his wife’s corpse was later discovered in an old mine shaft near Johnston City.

Birger was arrested for the murder of Joe Adams on April 29, 1927 and he was tried for murder that summer in Franklin County. In late July, after 24 hours of deliberation, the jury returned with its verdict, finding Birger guilty. He was sentenced to death, although was granted a stay of execution as he appealed the verdict. In late February 1928, the Illinois Supreme Court denied his appeal and sentenced him to die on April 13. Birger claimed to be relieved and said that he would rather die than spend another 10 months in jail.

Another appeal was attempted but turned down on April 12 by the State Board of Pardons and Paroles. After this failure, Birger’s lawyer rushed to Benton and field another petition. This one was in the name of Charlie’s nephew, Nathan Birger, and it asked for a sanity hearing. The execution was postponed again and on April 16, the hearing began. Birger made a desperate attempt to escape death, making a fool of himself by cursing at reporters, cowering and rolling his head from side to side. Spectators in the crowd actually laughed at him and the jury took just 12 minutes to find him totally sane. He was not scheduled to die on April 19.

He would be the last man to die on the gallows in the state of Illinois. During that same month, the Illinois legislature abolished hanging and substituted the electric chair as a humane method of execution in the state.

Thanks to Charlie’s notoriety, a “county fair atmosphere” was used to characterize the town of Benton on the day of the hanging. Thousands of people jammed to streets although only a few hundred of them actually had tickets to the execution.

Birger climbed the steps of the scaffold with a bright smile on his face, laughing and joking with the officials. “It’s a beautiful world,” he grinned and those became the last words of the man who had become a larger-than-life part of Little Egypt. Six minutes later, Charlie Birger was dead.