FOR ALL YOU CALIFORNIANS OUT THERE, SPECIFICALLY THOSE IN THE CENTRAL COAST AREA I RAN ACROSS THIS ARTICLE. THOUGHT IT WOULD BE NICE TO SHARE. I FISH LAKE CACHUMA WHICH IS DOWNSTREAM FROM THE PASS.

ENJOY!!

John C. Fremont's "Great Battle"

California belonged to Spain in the early 1800's. When Mexico broke away from Spain in 1837, California became Mexican territory. In the 1840's American pioneers started moving into California. They wanted it to be an American state. A war of independence was started between the United States and Mexico over California. Col. John C. Fremont, "The Pathfinder," was one of the American officers who fought in the war.

In 1846, John C. Fremont lead 300 American Troops through Foxen Canyon. He camped about a mile from Benjamin Foxen's ranch, near the present town of Sisquoc, in the hills east of Santa Maria. Foxen told Fremont about a short cut over the mountains to Santa Barbara. You've probably heard this story: Foxen told Fremont that the Mexican Army in Santa Barbara was lying in wait for him in narrow Gaviota Pass, ready to roll rocks on him and the soldiers. This story is false. The Mexican Army was in Los Angeles with General Pico's Army. Besides, Gaviota Pass was closed due to floods. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Foxen did tell Fremont about a short cut through the mountains. The troops left on Christmas Eve, 1848. It was raining hard, and the mud was slippery as they made their way up the narrow ridge over San Marcos Pass. Fremont lost 150 pack mules that night, but not one human life. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Fremont and his men were going to Santa Barbara to fight the Mexican Army, but the Mexicans were in Los Angeles. The only enemy left in Santa Barbara was Augustin Janssens, a ranch owner who was loyal to Spain. He only had fifteen cowboys fighting for him. He knew he'd lose the battle. He also knew knew that Fremont's men needed new horses. To make sure Fremont didn't steal any of his horses, he rounded them all up and hid them near the Santa Ynez River exactly where Cachuma Lake is now. Of course Janssens lost the fight. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Fremont hid one of his cannons in the brush because the mules pulling it had died. He was able to pull the rest of the cannons with horses. On December 27, 1846, the soldiers returned and couldn't find the hidden cannon. Captain McLain's journal described the cannon being hidden deep in the brush. No one ever found it, and I doubt they ever will. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 62.)

The cannon was hidden in a canyon near our house. My dad has looked for it. He says he's waiting for a brush fire to burn the chaparral. "We won't have a house, but I might find the cannon!"

Ten days after Fremont crossed the Pass to Santa Barbara, General Pico surrendered to him rather than suffer the casualties of war. (Tompkins, 1966, p. 48.) The California war was over. San Marcos Pass became part of the California Republic, and it became part of the U.S. in 1850.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Stagecoach Days

There is no way out north of Santa Barbara without crossing the Santa Ynez Mountains. The shortest way over the mountains is San Marcos Pass, so a stagecoach route was built. In 1868, Chinese workers started on both ends of the proposed route, following stakes put in the ground by road engineers. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 89)

The original stagecoach route started near Kellogg Avenue in Goleta. A half mile above Rancho del Ciervo, the road turned into a steep slope of sandstone, where the horses slipped and could not get up the rock. The Chinese workers had to chisel deep grooves into the rock so the horses could climb up. This section was known as Slippery Rock or "Slippery Sal." The road went on to Kinevan Ranch where the stagecoaches stopped and changed horses. From there, the road went over the summit and on down to Cold Springs Tavern. Then the stagecoaches went to Felix Mattei's Hotel in Los Olivos, now known as Mattei's Tavern, and on to Santa Maria. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 89.)

Stagecoach drivers often left the gate open at the bottom of Slippery Rock, and the ranchers complained. In 1892 a new road was built. San Marcos Road ("The Old Pass") follows that route today.

Patrick Kinevan's wife Nora sold meals and let people stay overnight for a bit of money. (Tompkins, 1982, p. 68.)

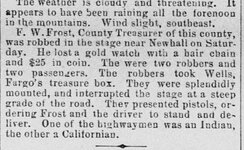

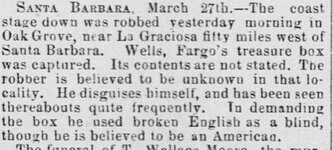

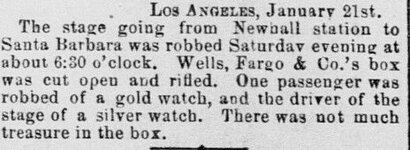

The Pass was filled with fearful bandits. Many stagecoaches didn't make it over the Pass without being robbed. The bandit problem was the worst during the 1850's. There were fewer sheriffs, and most bandits weren't caught. The favorite targets of most bandits were cattle buyers. They usually had their saddle bags filled with gold. (Tompkins, 1962, pp. 73-79.)

One of the greatest robberies happened in the 1850's, when a stagecoach was robbed on its way to the bank. The two bandits took a box filled with gold coins and ran into the hills with it to hide from the sheriff. A few days later the bandits were found. One was shot, the other was put in jail. Neither of them had the box of gold. While in jail the bandit got sick. Right before he died he told the sheriff that the box was buried in front of a tree where two streams come together. He died the next day. No one ever found the treasure, and I doubt they ever will. One day, a long time later, one of the descendants of Patrick Kinevan found a gold coin in the orchard near where we used to live. It was an unusual coin because of its octagonal shape, the same sort of coin that vanished in the robbery. He gave it to a priest from the Mission who shipped to to the Pope. (Tompkins, 1989, p. 122.)

My dad looked for the gold with a metal detector. Once while crawling under chaparral near the cabin, he found an old rock cairn and was sure he had it! But there was nothing under the rocks. I think the sheriff found the box of gold himself and didn't tell anyone in order to avoid taxes

ENJOY!!

John C. Fremont's "Great Battle"

California belonged to Spain in the early 1800's. When Mexico broke away from Spain in 1837, California became Mexican territory. In the 1840's American pioneers started moving into California. They wanted it to be an American state. A war of independence was started between the United States and Mexico over California. Col. John C. Fremont, "The Pathfinder," was one of the American officers who fought in the war.

In 1846, John C. Fremont lead 300 American Troops through Foxen Canyon. He camped about a mile from Benjamin Foxen's ranch, near the present town of Sisquoc, in the hills east of Santa Maria. Foxen told Fremont about a short cut over the mountains to Santa Barbara. You've probably heard this story: Foxen told Fremont that the Mexican Army in Santa Barbara was lying in wait for him in narrow Gaviota Pass, ready to roll rocks on him and the soldiers. This story is false. The Mexican Army was in Los Angeles with General Pico's Army. Besides, Gaviota Pass was closed due to floods. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Foxen did tell Fremont about a short cut through the mountains. The troops left on Christmas Eve, 1848. It was raining hard, and the mud was slippery as they made their way up the narrow ridge over San Marcos Pass. Fremont lost 150 pack mules that night, but not one human life. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Fremont and his men were going to Santa Barbara to fight the Mexican Army, but the Mexicans were in Los Angeles. The only enemy left in Santa Barbara was Augustin Janssens, a ranch owner who was loyal to Spain. He only had fifteen cowboys fighting for him. He knew he'd lose the battle. He also knew knew that Fremont's men needed new horses. To make sure Fremont didn't steal any of his horses, he rounded them all up and hid them near the Santa Ynez River exactly where Cachuma Lake is now. Of course Janssens lost the fight. (Tompkins, 1966, pp. 39-48.)

Fremont hid one of his cannons in the brush because the mules pulling it had died. He was able to pull the rest of the cannons with horses. On December 27, 1846, the soldiers returned and couldn't find the hidden cannon. Captain McLain's journal described the cannon being hidden deep in the brush. No one ever found it, and I doubt they ever will. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 62.)

The cannon was hidden in a canyon near our house. My dad has looked for it. He says he's waiting for a brush fire to burn the chaparral. "We won't have a house, but I might find the cannon!"

Ten days after Fremont crossed the Pass to Santa Barbara, General Pico surrendered to him rather than suffer the casualties of war. (Tompkins, 1966, p. 48.) The California war was over. San Marcos Pass became part of the California Republic, and it became part of the U.S. in 1850.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Stagecoach Days

There is no way out north of Santa Barbara without crossing the Santa Ynez Mountains. The shortest way over the mountains is San Marcos Pass, so a stagecoach route was built. In 1868, Chinese workers started on both ends of the proposed route, following stakes put in the ground by road engineers. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 89)

The original stagecoach route started near Kellogg Avenue in Goleta. A half mile above Rancho del Ciervo, the road turned into a steep slope of sandstone, where the horses slipped and could not get up the rock. The Chinese workers had to chisel deep grooves into the rock so the horses could climb up. This section was known as Slippery Rock or "Slippery Sal." The road went on to Kinevan Ranch where the stagecoaches stopped and changed horses. From there, the road went over the summit and on down to Cold Springs Tavern. Then the stagecoaches went to Felix Mattei's Hotel in Los Olivos, now known as Mattei's Tavern, and on to Santa Maria. (Tompkins, 1962, p. 89.)

Stagecoach drivers often left the gate open at the bottom of Slippery Rock, and the ranchers complained. In 1892 a new road was built. San Marcos Road ("The Old Pass") follows that route today.

Patrick Kinevan's wife Nora sold meals and let people stay overnight for a bit of money. (Tompkins, 1982, p. 68.)

The Pass was filled with fearful bandits. Many stagecoaches didn't make it over the Pass without being robbed. The bandit problem was the worst during the 1850's. There were fewer sheriffs, and most bandits weren't caught. The favorite targets of most bandits were cattle buyers. They usually had their saddle bags filled with gold. (Tompkins, 1962, pp. 73-79.)

One of the greatest robberies happened in the 1850's, when a stagecoach was robbed on its way to the bank. The two bandits took a box filled with gold coins and ran into the hills with it to hide from the sheriff. A few days later the bandits were found. One was shot, the other was put in jail. Neither of them had the box of gold. While in jail the bandit got sick. Right before he died he told the sheriff that the box was buried in front of a tree where two streams come together. He died the next day. No one ever found the treasure, and I doubt they ever will. One day, a long time later, one of the descendants of Patrick Kinevan found a gold coin in the orchard near where we used to live. It was an unusual coin because of its octagonal shape, the same sort of coin that vanished in the robbery. He gave it to a priest from the Mission who shipped to to the Pope. (Tompkins, 1989, p. 122.)

My dad looked for the gold with a metal detector. Once while crawling under chaparral near the cabin, he found an old rock cairn and was sure he had it! But there was nothing under the rocks. I think the sheriff found the box of gold himself and didn't tell anyone in order to avoid taxes