DeepseekerADS

Gold Member

- Mar 3, 2013

- 14,880

- 21,733

- Detector(s) used

- CTX, Excal II, EQ800, Fisher 1260X, Tesoro Royal Sabre, Tejon, Garrett ADSIII, Carrot, Stealth 920iX, Keene A52

- Primary Interest:

- Other

Here?s how bad it would be if Yellowstone?s supervolcano erupted today - Salon.com

This hypothetical is the stuff of nightmares

Lindsay Abrams

Beneath Yellowstone National Park, in Wyoming, there lies a massive volcano, also known as the Yellowstone Supervolcano. It’s erupted, spectacularly, three times over the past 2.1 million years: If you take the amount of ash produced from each, you’d have enough to fill the Grand Canyon. The last eruption occurred about 640,000 years ago, and at some point, it’s probably going to happen again. So here’s a fun hypothetical: What would happen if it did?

Scientists with the United States Geological Survey, partly to establish “quantitative research in terms of regional ashfall impacts” in the event of a modern-day eruption, and partly, I’d like to imagine, to fuel all of our nightmares, set out to investigate just that. Their results, published in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, indicate that things would get really bad, really quickly.

To be clear, the researchers caution that it’s very unlikely this will happen any time soon. But if it did? Whoa.

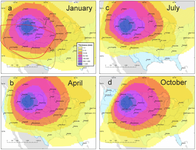

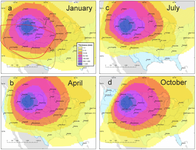

For starters, there’s the ash: computer modeling indicates that a supereruption (as befits a supervolcano) would spew about 240 miles of it into the atmosphere, effectively shutting down electronic communications and air travel throughout the continent as it dispersed in what’s known as an “umbrella” cloud. How it lands depends on wind conditions, but cities closest to the eruption could end up blanketed in up to a meter of ash; those on the East, West and Gulf Coast would get smaller, but still disruptive, ash deposits of their own.

Simulated tephra fall thickness resulting from a month-long Yellowstone eruption of 330 km3 using 2001 wind fields Wiley

Even in places where the ash layer is only millimeters thick, water supplies and crops would be ruined; it would be hard to drive, and people would develop respiratory problems. And the climate itself would change significantly. While there are no historical examples large enough to draw a comparison, the researchers note that the considerably smaller Tambora eruption of 1815 ”cooled the planet enough to produce the famed ‘year without a summer’ in 1816, during which snow fell in June in eastern North America and crop failures led to the worst famine of the 19th century.” The reality, they add, pales in comparison to some of the theories floating around on the Internet; apparently that’s meant to be reassuring.

“Geological activity at Yellowstone provides no signs that a supereruption will occur in the near future,” the researchers conclude, which is more reassuring. They add that they can say, with 99.9 percent certainty, that it’s not going to happen in the 21st century. To that we can add: We’d better hope so.

This hypothetical is the stuff of nightmares

Lindsay Abrams

Beneath Yellowstone National Park, in Wyoming, there lies a massive volcano, also known as the Yellowstone Supervolcano. It’s erupted, spectacularly, three times over the past 2.1 million years: If you take the amount of ash produced from each, you’d have enough to fill the Grand Canyon. The last eruption occurred about 640,000 years ago, and at some point, it’s probably going to happen again. So here’s a fun hypothetical: What would happen if it did?

Scientists with the United States Geological Survey, partly to establish “quantitative research in terms of regional ashfall impacts” in the event of a modern-day eruption, and partly, I’d like to imagine, to fuel all of our nightmares, set out to investigate just that. Their results, published in the journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, indicate that things would get really bad, really quickly.

To be clear, the researchers caution that it’s very unlikely this will happen any time soon. But if it did? Whoa.

For starters, there’s the ash: computer modeling indicates that a supereruption (as befits a supervolcano) would spew about 240 miles of it into the atmosphere, effectively shutting down electronic communications and air travel throughout the continent as it dispersed in what’s known as an “umbrella” cloud. How it lands depends on wind conditions, but cities closest to the eruption could end up blanketed in up to a meter of ash; those on the East, West and Gulf Coast would get smaller, but still disruptive, ash deposits of their own.

Simulated tephra fall thickness resulting from a month-long Yellowstone eruption of 330 km3 using 2001 wind fields Wiley

Even in places where the ash layer is only millimeters thick, water supplies and crops would be ruined; it would be hard to drive, and people would develop respiratory problems. And the climate itself would change significantly. While there are no historical examples large enough to draw a comparison, the researchers note that the considerably smaller Tambora eruption of 1815 ”cooled the planet enough to produce the famed ‘year without a summer’ in 1816, during which snow fell in June in eastern North America and crop failures led to the worst famine of the 19th century.” The reality, they add, pales in comparison to some of the theories floating around on the Internet; apparently that’s meant to be reassuring.

“Geological activity at Yellowstone provides no signs that a supereruption will occur in the near future,” the researchers conclude, which is more reassuring. They add that they can say, with 99.9 percent certainty, that it’s not going to happen in the 21st century. To that we can add: We’d better hope so.