- Jan 6, 2006

- 20,845

- 2,532

- 🏆 Honorable Mentions:

- 1

- Detector(s) used

- Garrett AT Pro, Ace 250 & Ace 400

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Like any coastal area, southern Louisiana is dotted with barrier islands like Grand Terre and Grand Isle and chenieres such as Chénière Caminada commonly called La Chénière (The Chénière) because it was the most prominent one. Cheniere is a local word meaning “oak ridge.”

In 1763 Monsieur Du Rollin was given a land grant to The Chénière which was later sold to Francisco Caminada who gave it his name. Land on Grand Isle wasn’t mentioned until the 1780’s when the Louisiana Territory was under Spanish control. The Spanish encouraged colonization, so land grantssplit the island among four men: Jacques Rigaud, Joseph Caillet, Francisco Anfrey and Charles Dufrene.

Grand Isle was separated from the finger of The Chénière by a narrow body of water called “the spit” because it was narrow enough to spit across.

Grand Isle was settled by the descendants of the original owners as well as other French Creoles. Caminadaville was settled by Acadians who had migrated down the bayou from the Acadian coast as well as Creoles and immigrants from other countries.

Early settlers of Chénière Caminada probably also included some of Jean Lafitte’s men. Lafitte and his band of pirates, or privateers as they wished to be called, had a base on Grand Terre but also frequented Grand Isle and Chénière Caminada. Researching the true pirate history of the area is difficult because, as Grace King wrote in her memories of Chénière Caminada in 1894, “such people do not keep official certificates of themselves”.

In the 1830’s the landowners on Grand Isle developed their land into large cotton and sugar cane plantations. The largest plantation of record was the Barataria Plantation which covered two miles of the island’s center. It had over 100 slaves and thirty-eight slave cabins. There was also a sugar house, blacksmith, carpenter shop and slave hospital. Plantations were active until the Civil War.

While plantations were cultivated on Grand Isle, Caminadaville remained dependent on hunting and fishing, but was becoming more urban than nearby Grand Isle. With a population of over 300, it even had a hotel to cater to tourists who came to the coast for surf-bathing.

Despite the proximity of two communities and a shared language and religion, they differed in most other respects. While Grand Isle was becoming a Creole resort community, with the occupants enjoying bright distractions like fishing, swimming and exploring, life on Chénière Caminada was more serious and remained fairly isolated from the outside world. Grand Isle had its tourists and summer residents; Chénière Caminada remained busy year around. The tourists may visit to see the Chinese “dance” the shrimp to remove the heads and shells.

Since Grand Isle didn’t have a church, tourists would attend Sunday Mass on The Chénière. But they considered the people of Caminadaville to be socially inferior to them.

The residents of Caminadaville were hardworking people, but Sunday was reserved as a day of rest, relaxation and religion. Father Gaston d’Espinose arrived in 1882. Unwelcome at Grand Isle, he went to Chénière where he was taken in. His mother donated money to build the Catholic church there, and in Chénière Caminada: Another Look by Rousse it’s noted that the church bell is said to have been cast from 700 pounds of gold and silver, including Father d’Espinose’s crested family plate, prized heirlooms of his parishioners, and pirate booty. By the 1890’s Caminadaville had become a town of about 180 buildings including the Catholic church, four stores, a post office, a school and a combination boarding house/resort.

Developers responded the trend of increased relaxation and resorts grew in number and popularity in the south and northeast.

Even without this growing popularity, residents of New Orleans had numerous reasons for going to resorts including civil and political unrest, labor problems, crime, drugs, heat, humidity, and poor sanitation. The city was a hotbed of disease due in part to the limited sanitation methods and the daily arrival of immigrants with almost every sickness imaginable. During the summer months the addition of heat and humidity caused some of these outbreaks to reach epidemic proportions. The most devastating of these epidemics was yellow fever.

It had long been recognized that Grand Isle could be a successful resort area. The first Grand Isle resort of the Gilded Age was a dream of the entrepreneur and developer of the Harvey Canal, Joseph Hale Harvey. He, along with Benjamin Margot, bought out the Barataria Plantation after the Civil War. They developed it into an appealing resort as described by Evans, Stielow and Swanson their history, Grand Isle on the Gulf:

The remodeled slave cabins, laid out in double rows between “streets” lined with trees, became cozy cottages for the reception of guests. The sugarhouse was divided into two large rooms. One served as a huge dining hall.The other contained a piano and was used as a dance hall. A large clientele could be lodged in the old plantation residence which also held the office,bar-room, and billiard room. To the delight of the largely Creole patrons,several hotel servants were imported from France, Italy, and Bavaria.

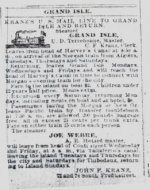

Harvey offered excursions to the island and advertised the resort, targeting the elite of New Orleans, the family-oriented French Creoles. Steamers ran three days a week from New Orleans to Grand Isle.

Harvey envisioned transforming Grand Isle into one of the most renowned resorts in the United States. The Grand Isle resorts represented a type of resort identified as “home” resorts. These establishments provided a summer refuge for families that was within commuting distance of urban work places. The families spent the summer there, with the patriarch spending the week working and joining the family for the weekends. The resort became a summer residence for many Creole families, a respite from the city. Despite the popularity of the resort, the financial Panic of 1873 caused a slowdown in tourism, and the Grand Isle Hotel went bankrupt.

In 1878 the hotel was sold to John F. Krantz who reopened it just in time for another devastating yellow jack epidemic. The successful resort that Krantz established encouraged others to follow suit.

Resorts gave new opportunities to women of the time, who were the principal occupants. It allowed them to view life in a different light. Many of the eastern resorts were viewed as places to meet a mate, but Grand Isle, as a home resort, did not follow suit. But it was not unheard of for women who were left alone for the summer to engage in affairs

In the early 1890’s P. F. Herwig had built a hotel and was collecting materials to build another. There were plans to develop resorts on Grande Terre and Chénière Caminada. In 1892 the Luxurious Ocean Club was opened for business.The major pastime was surf-bathing and a tram was provided to transport residents from the resort to the beach. Summer residents also enjoyed hunting, fishing, sailing, exploring, and relaxing in an atmosphere that was free of stress. On the weekends there were dances, parties and gambling.

In 1763 Monsieur Du Rollin was given a land grant to The Chénière which was later sold to Francisco Caminada who gave it his name. Land on Grand Isle wasn’t mentioned until the 1780’s when the Louisiana Territory was under Spanish control. The Spanish encouraged colonization, so land grantssplit the island among four men: Jacques Rigaud, Joseph Caillet, Francisco Anfrey and Charles Dufrene.

Original Land Grants of Grand Isle

Grand Isle was separated from the finger of The Chénière by a narrow body of water called “the spit” because it was narrow enough to spit across.

Grand Isle was settled by the descendants of the original owners as well as other French Creoles. Caminadaville was settled by Acadians who had migrated down the bayou from the Acadian coast as well as Creoles and immigrants from other countries.

Early settlers of Chénière Caminada probably also included some of Jean Lafitte’s men. Lafitte and his band of pirates, or privateers as they wished to be called, had a base on Grand Terre but also frequented Grand Isle and Chénière Caminada. Researching the true pirate history of the area is difficult because, as Grace King wrote in her memories of Chénière Caminada in 1894, “such people do not keep official certificates of themselves”.

In the 1830’s the landowners on Grand Isle developed their land into large cotton and sugar cane plantations. The largest plantation of record was the Barataria Plantation which covered two miles of the island’s center. It had over 100 slaves and thirty-eight slave cabins. There was also a sugar house, blacksmith, carpenter shop and slave hospital. Plantations were active until the Civil War.

While plantations were cultivated on Grand Isle, Caminadaville remained dependent on hunting and fishing, but was becoming more urban than nearby Grand Isle. With a population of over 300, it even had a hotel to cater to tourists who came to the coast for surf-bathing.

Despite the proximity of two communities and a shared language and religion, they differed in most other respects. While Grand Isle was becoming a Creole resort community, with the occupants enjoying bright distractions like fishing, swimming and exploring, life on Chénière Caminada was more serious and remained fairly isolated from the outside world. Grand Isle had its tourists and summer residents; Chénière Caminada remained busy year around. The tourists may visit to see the Chinese “dance” the shrimp to remove the heads and shells.

Since Grand Isle didn’t have a church, tourists would attend Sunday Mass on The Chénière. But they considered the people of Caminadaville to be socially inferior to them.

The residents of Caminadaville were hardworking people, but Sunday was reserved as a day of rest, relaxation and religion. Father Gaston d’Espinose arrived in 1882. Unwelcome at Grand Isle, he went to Chénière where he was taken in. His mother donated money to build the Catholic church there, and in Chénière Caminada: Another Look by Rousse it’s noted that the church bell is said to have been cast from 700 pounds of gold and silver, including Father d’Espinose’s crested family plate, prized heirlooms of his parishioners, and pirate booty. By the 1890’s Caminadaville had become a town of about 180 buildings including the Catholic church, four stores, a post office, a school and a combination boarding house/resort.

Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church at Chénière Caminada in 1891

Developers responded the trend of increased relaxation and resorts grew in number and popularity in the south and northeast.

Even without this growing popularity, residents of New Orleans had numerous reasons for going to resorts including civil and political unrest, labor problems, crime, drugs, heat, humidity, and poor sanitation. The city was a hotbed of disease due in part to the limited sanitation methods and the daily arrival of immigrants with almost every sickness imaginable. During the summer months the addition of heat and humidity caused some of these outbreaks to reach epidemic proportions. The most devastating of these epidemics was yellow fever.

It had long been recognized that Grand Isle could be a successful resort area. The first Grand Isle resort of the Gilded Age was a dream of the entrepreneur and developer of the Harvey Canal, Joseph Hale Harvey. He, along with Benjamin Margot, bought out the Barataria Plantation after the Civil War. They developed it into an appealing resort as described by Evans, Stielow and Swanson their history, Grand Isle on the Gulf:

The remodeled slave cabins, laid out in double rows between “streets” lined with trees, became cozy cottages for the reception of guests. The sugarhouse was divided into two large rooms. One served as a huge dining hall.The other contained a piano and was used as a dance hall. A large clientele could be lodged in the old plantation residence which also held the office,bar-room, and billiard room. To the delight of the largely Creole patrons,several hotel servants were imported from France, Italy, and Bavaria.

Harvey offered excursions to the island and advertised the resort, targeting the elite of New Orleans, the family-oriented French Creoles. Steamers ran three days a week from New Orleans to Grand Isle.

Advertisement for The Grand Isle Hotel

From New Orleans Times-Democrat, July 27, 1882

From New Orleans Times-Democrat, July 27, 1882

Harvey envisioned transforming Grand Isle into one of the most renowned resorts in the United States. The Grand Isle resorts represented a type of resort identified as “home” resorts. These establishments provided a summer refuge for families that was within commuting distance of urban work places. The families spent the summer there, with the patriarch spending the week working and joining the family for the weekends. The resort became a summer residence for many Creole families, a respite from the city. Despite the popularity of the resort, the financial Panic of 1873 caused a slowdown in tourism, and the Grand Isle Hotel went bankrupt.

In 1878 the hotel was sold to John F. Krantz who reopened it just in time for another devastating yellow jack epidemic. The successful resort that Krantz established encouraged others to follow suit.

Resorts gave new opportunities to women of the time, who were the principal occupants. It allowed them to view life in a different light. Many of the eastern resorts were viewed as places to meet a mate, but Grand Isle, as a home resort, did not follow suit. But it was not unheard of for women who were left alone for the summer to engage in affairs

In the early 1890’s P. F. Herwig had built a hotel and was collecting materials to build another. There were plans to develop resorts on Grande Terre and Chénière Caminada. In 1892 the Luxurious Ocean Club was opened for business.The major pastime was surf-bathing and a tram was provided to transport residents from the resort to the beach. Summer residents also enjoyed hunting, fishing, sailing, exploring, and relaxing in an atmosphere that was free of stress. On the weekends there were dances, parties and gambling.