Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,474

- 3,794

from the Arizona Weekly Enterprise, September 7, 1889

I am responsible for the traditions related in those wonderful articles and for nothing more. I have discovered no mines, neither “lost mines” nor others. I went to survey and not to prospect, my expedition was one of discovery, it is true, but I was hunting lands and not mines. A prospectors party did accompany my party, but long before we reached the Sierra Madre [it ?] went its ways and left me to go mine. This party did denounce certain old mines situated on the western slope of the Sierra Madre, in what was once the Mining District of Ostinuri, but they were not “lost mines.” There is not a miner in Sonora who does not know more or less about them, not a few who have sought and expected to find unbounded wealth in them because they had a “tradition,” and there is not one of them who ever took out of any of them what he put in. For many it is sufficient that a Mexican mine has a “tradition.” It is of little moment what that “tradition” may be. Lest, therefore, some of your readers, with a penchant for lost mines in Mexico, may like the Arabs,

“Quietly fold their tents,

and silently steal away”

to this land of “lost mines” and “traditions,” I will tell you exactly what the “tradition” really is in regard to the District of Ostinuri. This District was originally very large, but was finally reduced so much as to be comprised nearly within the triangle of which Mulatos, Trinidad and Maicoha are the vertices. You will find these points on any recent map of Sonora. Ostinuri was originally the capital, but lost its importance more than a century ago, as did also the District, and even at that time the “lost mines” of which we hear so much, were “lost” and had their “tradition.” Colonel “Don Antonio de Alcedo, Captain of the Spanish Guards, of the Royal Academy of History, etc.” in is “Historico-Geographical Dictionary of te West Indies or America” (Madria 1788) says of Ostinuri, “There are many mines of gold and silver, the ores of which are of very low grade, and which have been very little worked.” This then is the true “tradition” of the “lost mines” reported discovered by me and said to be fabulously rich.

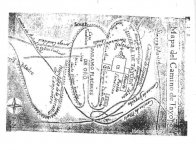

Detail: Map of the Gadsden Purchase : Sonora and portions of New Mexico, Chihuaua & California / by Herman Ehrenberg from his private notes and those of Colonel Grey ; Maj. Heintzelman, Liet. Parks and others. The Yaqui, Mayo and Fuerte Valleys are by A. Fleury, Military Eng. of Sonora. [1858]

According to “traditions” to be heard every where in Mexico there were seven remarkably rich mines situated somewhere in western Chihuahua or eastern Sonora. The inhabitants of these mining camps were killed in an Indian uprising and every trace of them as disappeared. Among these mines Guaynopa and one other were exceptionally rich both in grade and in quantity. None of them have ever been found. It is known that what is now called Guaynopa is not the Guaynopa but Santa Fe de Rodriguez.

An important discovery has, however, been made respecting this “other” mine referred to alone, which may possible lead to the discovery of some or all of the others. This one, least, is much older than it has been thought to be. The discovery is one of documents and was made in this manner, so I am informed. Some months since an individual lie dying in an interior town of Sonora. He had an intimate friend summoned and told him substantially as follows: “My grandfather on this death bed told my father that in a certain town in a certain corner of the church there was buried an immense chest containing important documents. This fact has been handed down from father to son. I am the last male of that line. If you will go there you will find them. I dont know what they contain.” The person who received this information attached but little importance to it at the time but finally decided to investigate and see what there was in it. With a few friends he went to the place, which was readily found though in ruins and after considerable work found the box and the documents. The foregoing may be some body’s version of the matter, but the documents exist and are unquestionably genuine. They are over two hundred years old, and begin with the statement that the Indians are restless, than an uprising is imminent, and that preparations have been made for defense. This document with others were enclosed in a box and sent to the church in a certain town for safe keeping. It describes in great detail everything about the mine, even to the number of men, women, and children there, their nationality and occupation; describes the bells and their inscriptions, the distances and directions from there to every mining camp and town in the District - gives fifteen as the number of mines being worked in the camp; describes the vault in which were deposited even cargos (300 lbs) of gold bullion and two hundred of silver; describes each of the fifteen mines, the distances from one to the other, the class of ores from each and their value; describes one in particular that runs $24,000 in gold. These documents contain in fact a detailed account of the discovery and working of these mines, and of everything in the District as it existed at that time and was signed by seven friars. The Indians did break out and every vestige of this and other camps was effectually wiped out, and nothing was left but “tradition,” so far as known, until these documents were found. They have been carefully compared with other documents of the same period and with the general history of that time and their dates fully coincide. An expedition was organized to hunt for the mine but has not yet started for serious reasons which I am not at liberty to make public. Should this mine be found, it will undoubtedly lead to discovery of the others connected with it in tradition and will give the country such a boom as it never had before. I vouch for all I have said in regard to the existence and contents of these documents, but am prohibited from giving the name of the mine, its location or why the search for it has not yet been made.

I consider the discovery of these documents important. I believe others exist in the churches, especially in those in the mountain towns of Chihuahua and Sonora, which the Mexican government ought to collect and preserve. I believe there is much valuable matter regarding the discovery and working of mines, and the country in general, among the records of births, deaths and marriages stored away in these old churches, that ought to be examined, collated and preserved. That part of the Sierra Madre is terra incognita, and yet there exist on every hand evidences of human occupation, historic as well as prehistoric terraces, ruins of towns, of mining camps, dumps everywhere, arastras, smelting furnaces, dams, irrigating ditches, etc. Fruit trees are found everywhere, peaches, figs, pomegranates pears, apples, etc. I have even seen onions and potatoes. Colonel Alcedo says the country was occupied by many tribes of Indians. Even they have disappeared or exist only in the half breed Mexican, the Apache, the Tarahumara, the Pina, the Oputa or the Maicobeno. These have all degenerated and the country is open once again, after over two centuries, to the adventurous prospector and miner. Humboldt and Ward both prophesied that richer mines, both in quality and quantity would be found in this part of Mexico than in the older and more developed districts of the South and that they would pay from the surface down. Will this prophesy be verified.

H. O. Flipper.

____________

Editor’s Notes

“Of all the men who have set out on the trail for Tayopa, no one has searched for its record so assiduously as Henry O. Flipper.” - J. Frank Dobie, Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver (1928). Prof. Dobie references “the Flipper report,” but provides no link to it.

Henry Ossian Flipper was born in Thomasville, Georgia, on March 21, 1856, into slavery and spent his formative years in Georgia. Following the Civil War, he attended the American Missionary Association Schools in his home state. In 1873 Flipper was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy, and in 1877 he became the first African-American to graduate from the Institution [he graduated 50th in a class of 76; he was the fifth African-American cadet]. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and assigned to the 10[SUP]th[/SUP] Cavalry. From 1878 until 1880 Lieutenant Flipper served on frontier duty in various installations in the Southwest, including Fort Still, Oklahoma. His duties included scouting, as well as serving as post engineer, surveyor and construction supervisor, post adjutant, acting assistant and post quartermaster, and commissary officer.

In 1881, Lieutenant Flipper’s commanding officer accused him of “embezzling funds and of conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.” As a result of these charges, he was court-martialed.

He was acquitted of the embezzlement charge but was found guilty, by General Court Martial, of conduct unbecoming an officer. On June 30, 1882, he was dismissed from the Army as required by this conviction.

…

Throughout the balance of his life, Henry Flipper maintained that he was innocent of the charges that resulted in his court-martial and dismissal from the Army and made numerous attempts to have his conviction reversed. He died in Georgia in 1940.

In 1976 descendants and supporters applied to the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records on behalf of Lieutenant Flipper. The Board, after stating that it did not have the authority to overturn his court-martial convictions, concluded the conviction and punishment were "unduly harsh and unjust" and recommended that Lieutenant Flipper's dismissal commuted to a good conduct discharge. The Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs) and The Adjutant General approved the Board's findings, conclusions and recommendations and directed that the Department of the Army issue Lieutenant Flipper a Certificate of Honorable Discharge, dated 30 June 1882, in lieu of his dismissal on the same date.

On October 21, 1997, a private law firm filed an application of pardon with the Secretary of the Army on Lieutenant Flipper's behalf… President William Jefferson Clinton pardoned Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper on February 19, 1999. In pardoning this officer, the President recognized an error and acknowledged the lifetime accomplishments of this American soldier.

http://www.history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/flipper.html

$3,791.77 in missing commissary funds! How much was that, back then? It was an eagle sum. It is always risky to attempt to compare monetary values from different eras. However, a Sergeant Major during the Civil War earned about $23 a month - a private $13. From memory, Army wages were reduced during the Indian Wars period (in fact, in one year the US Congress simply failed to pass a War Department appropriations bill that included paying the Army!). In very general terms, the missing money probably amounted to between seven and ten years pay for a Second Lieutenant.

He went to El Paso after his dismissal and remained there until 1883, when he went to work as an assistant engineer for a surveying company composed of former Confederate officers. He assisted the company in surveying public lands in Mexico and helped run a boundary line between the states of Coahuila and Chihuahua in 1883. Between 1883 and 1891 he worked in Chihuahua and Sonora as a surveyor for several other American land companies. In 1887 he opened a civil and mining engineering office in Nogales, Arizona. In 1891 the community of Nogales employed Flipper to prepare the Nogales de Elias land grant case (1893), a dispute over title to the San Juan de las Boquillas y Nogales Mexican land grant in Cochise County, Arizona. Flipper served as the government's only witness, and his testimony resulted in the grant's being declared invalid. The ruling saved the property of hundreds of landowners. Flipper's activity in the community led to his appointment as a special agent for the United States Court of Private Land Claims. In that position he worked on court materials, served as an expert on penmanship, and surveyed land grants in southern Arizona. In 1892, before the Nogales case, he compiled and translated Mining Law of the United States of Mexico and the Law on the Federal Property Tax on Mines. In 1895 the United States government published his translation of Spanish and Mexican Land Laws: New Spain and Mexico. Flipper also briefly edited the Nogales Sunday Herald and published articles in Old Santa Fe, which later became the New Mexico Historical Review. He became a member of the Association of Arizona Civil Engineers, the National Geographic Society, and the Southwest Society of the Archaeological Institute of America. He offered to serve in the Spanish-American War in 1898, but bills in the United States House of Representatives and in the Senate to restore his rank both died in committee. He served in the court of private land claims until 1901.

Beginning in 1901 Flipper spent eleven years in northern Mexico as an engineer and legal assistant to mining companies. He joined the Balvanera Mining Company in 1901 and remained as keeper of the company's property when it folded in 1903. William C. Greene bought the company in 1905 [when he was one of the richest businessmen not only in the United States but in the world; within a year he would be wiped out], renamed it the Gold-Silver Company, and placed Flipper in the legal department, where he handled land claims and sales and kept mining crews out of trouble with the local authorities. Greene, who had learned earlier of Flipper's research on the Lost Tayopa Mine, sent him to Spain to do more investigation. The story of Flipper and the Lost Tayopa Mine appears in J. Frank Dobie's Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver. In 1908 Albert B. Fall [later United States Senator from New Mexico and then Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, known for his role in the Teapot Dome scandal] bought out William C. Greene to form the Sierra Mining Company and retained Flipper in the legal department. In 1912 Flipper moved to El Paso, and in 1913 he began supplying information on conditions in revolutionary Mexico to Senator Fall's subcommittee on Mexican internal affairs. Flipper drew national attention when he was reported to be in league with Francisco (Pancho) Villa and denied the rumor in a letter to the Washington Eagle dated May 4, 1916. Flipper published an article, "Early History of El Paso," and also reputedly wrote a pamphlet entitled Did a Negro Discover Arizona and New Mexico?, which concerned itself with Estevanico's role in the Marcos de Niza expedition in 1539. In 1916 Flipper wrote a memoir of his life in the Southwest, which was published posthumously as Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper (1963) [Edited by Theodore D. Harris, it has been reprinted as Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper, First Black Graduate of West Point (1997) - it is rather pricy in the original (hardcover or wraps)].

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ffl13

------- o0o --------

Flipper’s autobiography, The Colored Cadet at West Point, first published in 1878, remains in print.

Flipper’s comments on this District proved prescient. A cursory search on the Internet shows considerable successful mining activity down to the present day. This was also predicted in “The Guaynopa District of Chihuahua; Completion of the Mexican Northwestern Railway will Open Important Mineral Sections Not Far from the United States Border. Copper. Silver. Lead and Gold” by William B. Phillips [Mining Engineer, Austin, Texas] in Mining Science; A Weekly Journal Devoted to Mining, Metallurgy and Engineering [Denver, Colorado] September 29, 1910 (Vol. LXII, 1600).

For more on the fascinating life and times of “Col.” William C. Greene, the best book is Colonel Greene and the Copper Skyrocket; The Spectacular Rise and Fall of William Cornell Greene, Copper King, Cattle Baron and Promoter, by Charles Leland Sonnichsen (1974). I recall KvonM recommending it when it was published.

LOST MINES IN MEXICO.

________________

An Important Discovery.

[El Paso Bullion.]

NOGALES, Arizona, August 21, 1889

You and your readers will undoubtedly recall the articles published in the Globe Democrat and other eastern papers, during the summer of 1887, on the discovery of certain “lost mines” in the Sierra Madre by myself and other persons. I have never thought it worth the trouble to state publicly what was really my connection with that “wonderfull discovery,” though to my friends I have often given the exact facts. An opportunity is now offered to do so in connection with what is really a discovery as remarkable as [it is?] important and of the certainty of which I can vouch.________________

An Important Discovery.

[El Paso Bullion.]

NOGALES, Arizona, August 21, 1889

I am responsible for the traditions related in those wonderful articles and for nothing more. I have discovered no mines, neither “lost mines” nor others. I went to survey and not to prospect, my expedition was one of discovery, it is true, but I was hunting lands and not mines. A prospectors party did accompany my party, but long before we reached the Sierra Madre [it ?] went its ways and left me to go mine. This party did denounce certain old mines situated on the western slope of the Sierra Madre, in what was once the Mining District of Ostinuri, but they were not “lost mines.” There is not a miner in Sonora who does not know more or less about them, not a few who have sought and expected to find unbounded wealth in them because they had a “tradition,” and there is not one of them who ever took out of any of them what he put in. For many it is sufficient that a Mexican mine has a “tradition.” It is of little moment what that “tradition” may be. Lest, therefore, some of your readers, with a penchant for lost mines in Mexico, may like the Arabs,

“Quietly fold their tents,

and silently steal away”

to this land of “lost mines” and “traditions,” I will tell you exactly what the “tradition” really is in regard to the District of Ostinuri. This District was originally very large, but was finally reduced so much as to be comprised nearly within the triangle of which Mulatos, Trinidad and Maicoha are the vertices. You will find these points on any recent map of Sonora. Ostinuri was originally the capital, but lost its importance more than a century ago, as did also the District, and even at that time the “lost mines” of which we hear so much, were “lost” and had their “tradition.” Colonel “Don Antonio de Alcedo, Captain of the Spanish Guards, of the Royal Academy of History, etc.” in is “Historico-Geographical Dictionary of te West Indies or America” (Madria 1788) says of Ostinuri, “There are many mines of gold and silver, the ores of which are of very low grade, and which have been very little worked.” This then is the true “tradition” of the “lost mines” reported discovered by me and said to be fabulously rich.

Detail: Map of the Gadsden Purchase : Sonora and portions of New Mexico, Chihuaua & California / by Herman Ehrenberg from his private notes and those of Colonel Grey ; Maj. Heintzelman, Liet. Parks and others. The Yaqui, Mayo and Fuerte Valleys are by A. Fleury, Military Eng. of Sonora. [1858]

According to “traditions” to be heard every where in Mexico there were seven remarkably rich mines situated somewhere in western Chihuahua or eastern Sonora. The inhabitants of these mining camps were killed in an Indian uprising and every trace of them as disappeared. Among these mines Guaynopa and one other were exceptionally rich both in grade and in quantity. None of them have ever been found. It is known that what is now called Guaynopa is not the Guaynopa but Santa Fe de Rodriguez.

An important discovery has, however, been made respecting this “other” mine referred to alone, which may possible lead to the discovery of some or all of the others. This one, least, is much older than it has been thought to be. The discovery is one of documents and was made in this manner, so I am informed. Some months since an individual lie dying in an interior town of Sonora. He had an intimate friend summoned and told him substantially as follows: “My grandfather on this death bed told my father that in a certain town in a certain corner of the church there was buried an immense chest containing important documents. This fact has been handed down from father to son. I am the last male of that line. If you will go there you will find them. I dont know what they contain.” The person who received this information attached but little importance to it at the time but finally decided to investigate and see what there was in it. With a few friends he went to the place, which was readily found though in ruins and after considerable work found the box and the documents. The foregoing may be some body’s version of the matter, but the documents exist and are unquestionably genuine. They are over two hundred years old, and begin with the statement that the Indians are restless, than an uprising is imminent, and that preparations have been made for defense. This document with others were enclosed in a box and sent to the church in a certain town for safe keeping. It describes in great detail everything about the mine, even to the number of men, women, and children there, their nationality and occupation; describes the bells and their inscriptions, the distances and directions from there to every mining camp and town in the District - gives fifteen as the number of mines being worked in the camp; describes the vault in which were deposited even cargos (300 lbs) of gold bullion and two hundred of silver; describes each of the fifteen mines, the distances from one to the other, the class of ores from each and their value; describes one in particular that runs $24,000 in gold. These documents contain in fact a detailed account of the discovery and working of these mines, and of everything in the District as it existed at that time and was signed by seven friars. The Indians did break out and every vestige of this and other camps was effectually wiped out, and nothing was left but “tradition,” so far as known, until these documents were found. They have been carefully compared with other documents of the same period and with the general history of that time and their dates fully coincide. An expedition was organized to hunt for the mine but has not yet started for serious reasons which I am not at liberty to make public. Should this mine be found, it will undoubtedly lead to discovery of the others connected with it in tradition and will give the country such a boom as it never had before. I vouch for all I have said in regard to the existence and contents of these documents, but am prohibited from giving the name of the mine, its location or why the search for it has not yet been made.

I consider the discovery of these documents important. I believe others exist in the churches, especially in those in the mountain towns of Chihuahua and Sonora, which the Mexican government ought to collect and preserve. I believe there is much valuable matter regarding the discovery and working of mines, and the country in general, among the records of births, deaths and marriages stored away in these old churches, that ought to be examined, collated and preserved. That part of the Sierra Madre is terra incognita, and yet there exist on every hand evidences of human occupation, historic as well as prehistoric terraces, ruins of towns, of mining camps, dumps everywhere, arastras, smelting furnaces, dams, irrigating ditches, etc. Fruit trees are found everywhere, peaches, figs, pomegranates pears, apples, etc. I have even seen onions and potatoes. Colonel Alcedo says the country was occupied by many tribes of Indians. Even they have disappeared or exist only in the half breed Mexican, the Apache, the Tarahumara, the Pina, the Oputa or the Maicobeno. These have all degenerated and the country is open once again, after over two centuries, to the adventurous prospector and miner. Humboldt and Ward both prophesied that richer mines, both in quality and quantity would be found in this part of Mexico than in the older and more developed districts of the South and that they would pay from the surface down. Will this prophesy be verified.

H. O. Flipper.

____________

Editor’s Notes

“Of all the men who have set out on the trail for Tayopa, no one has searched for its record so assiduously as Henry O. Flipper.” - J. Frank Dobie, Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver (1928). Prof. Dobie references “the Flipper report,” but provides no link to it.

------- o0o -------

Henry Ossian Flipper was born in Thomasville, Georgia, on March 21, 1856, into slavery and spent his formative years in Georgia. Following the Civil War, he attended the American Missionary Association Schools in his home state. In 1873 Flipper was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy, and in 1877 he became the first African-American to graduate from the Institution [he graduated 50th in a class of 76; he was the fifth African-American cadet]. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant and assigned to the 10[SUP]th[/SUP] Cavalry. From 1878 until 1880 Lieutenant Flipper served on frontier duty in various installations in the Southwest, including Fort Still, Oklahoma. His duties included scouting, as well as serving as post engineer, surveyor and construction supervisor, post adjutant, acting assistant and post quartermaster, and commissary officer.

In 1881, Lieutenant Flipper’s commanding officer accused him of “embezzling funds and of conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.” As a result of these charges, he was court-martialed.

He was acquitted of the embezzlement charge but was found guilty, by General Court Martial, of conduct unbecoming an officer. On June 30, 1882, he was dismissed from the Army as required by this conviction.

…

Throughout the balance of his life, Henry Flipper maintained that he was innocent of the charges that resulted in his court-martial and dismissal from the Army and made numerous attempts to have his conviction reversed. He died in Georgia in 1940.

In 1976 descendants and supporters applied to the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records on behalf of Lieutenant Flipper. The Board, after stating that it did not have the authority to overturn his court-martial convictions, concluded the conviction and punishment were "unduly harsh and unjust" and recommended that Lieutenant Flipper's dismissal commuted to a good conduct discharge. The Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs) and The Adjutant General approved the Board's findings, conclusions and recommendations and directed that the Department of the Army issue Lieutenant Flipper a Certificate of Honorable Discharge, dated 30 June 1882, in lieu of his dismissal on the same date.

On October 21, 1997, a private law firm filed an application of pardon with the Secretary of the Army on Lieutenant Flipper's behalf… President William Jefferson Clinton pardoned Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper on February 19, 1999. In pardoning this officer, the President recognized an error and acknowledged the lifetime accomplishments of this American soldier.

http://www.history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/flipper.html

------- o0o -------

$3,791.77 in missing commissary funds! How much was that, back then? It was an eagle sum. It is always risky to attempt to compare monetary values from different eras. However, a Sergeant Major during the Civil War earned about $23 a month - a private $13. From memory, Army wages were reduced during the Indian Wars period (in fact, in one year the US Congress simply failed to pass a War Department appropriations bill that included paying the Army!). In very general terms, the missing money probably amounted to between seven and ten years pay for a Second Lieutenant.

------- o0o -------

He went to El Paso after his dismissal and remained there until 1883, when he went to work as an assistant engineer for a surveying company composed of former Confederate officers. He assisted the company in surveying public lands in Mexico and helped run a boundary line between the states of Coahuila and Chihuahua in 1883. Between 1883 and 1891 he worked in Chihuahua and Sonora as a surveyor for several other American land companies. In 1887 he opened a civil and mining engineering office in Nogales, Arizona. In 1891 the community of Nogales employed Flipper to prepare the Nogales de Elias land grant case (1893), a dispute over title to the San Juan de las Boquillas y Nogales Mexican land grant in Cochise County, Arizona. Flipper served as the government's only witness, and his testimony resulted in the grant's being declared invalid. The ruling saved the property of hundreds of landowners. Flipper's activity in the community led to his appointment as a special agent for the United States Court of Private Land Claims. In that position he worked on court materials, served as an expert on penmanship, and surveyed land grants in southern Arizona. In 1892, before the Nogales case, he compiled and translated Mining Law of the United States of Mexico and the Law on the Federal Property Tax on Mines. In 1895 the United States government published his translation of Spanish and Mexican Land Laws: New Spain and Mexico. Flipper also briefly edited the Nogales Sunday Herald and published articles in Old Santa Fe, which later became the New Mexico Historical Review. He became a member of the Association of Arizona Civil Engineers, the National Geographic Society, and the Southwest Society of the Archaeological Institute of America. He offered to serve in the Spanish-American War in 1898, but bills in the United States House of Representatives and in the Senate to restore his rank both died in committee. He served in the court of private land claims until 1901.

Beginning in 1901 Flipper spent eleven years in northern Mexico as an engineer and legal assistant to mining companies. He joined the Balvanera Mining Company in 1901 and remained as keeper of the company's property when it folded in 1903. William C. Greene bought the company in 1905 [when he was one of the richest businessmen not only in the United States but in the world; within a year he would be wiped out], renamed it the Gold-Silver Company, and placed Flipper in the legal department, where he handled land claims and sales and kept mining crews out of trouble with the local authorities. Greene, who had learned earlier of Flipper's research on the Lost Tayopa Mine, sent him to Spain to do more investigation. The story of Flipper and the Lost Tayopa Mine appears in J. Frank Dobie's Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver. In 1908 Albert B. Fall [later United States Senator from New Mexico and then Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, known for his role in the Teapot Dome scandal] bought out William C. Greene to form the Sierra Mining Company and retained Flipper in the legal department. In 1912 Flipper moved to El Paso, and in 1913 he began supplying information on conditions in revolutionary Mexico to Senator Fall's subcommittee on Mexican internal affairs. Flipper drew national attention when he was reported to be in league with Francisco (Pancho) Villa and denied the rumor in a letter to the Washington Eagle dated May 4, 1916. Flipper published an article, "Early History of El Paso," and also reputedly wrote a pamphlet entitled Did a Negro Discover Arizona and New Mexico?, which concerned itself with Estevanico's role in the Marcos de Niza expedition in 1539. In 1916 Flipper wrote a memoir of his life in the Southwest, which was published posthumously as Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper (1963) [Edited by Theodore D. Harris, it has been reprinted as Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper, First Black Graduate of West Point (1997) - it is rather pricy in the original (hardcover or wraps)].

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ffl13

------- o0o --------

Flipper’s autobiography, The Colored Cadet at West Point, first published in 1878, remains in print.

Flipper’s comments on this District proved prescient. A cursory search on the Internet shows considerable successful mining activity down to the present day. This was also predicted in “The Guaynopa District of Chihuahua; Completion of the Mexican Northwestern Railway will Open Important Mineral Sections Not Far from the United States Border. Copper. Silver. Lead and Gold” by William B. Phillips [Mining Engineer, Austin, Texas] in Mining Science; A Weekly Journal Devoted to Mining, Metallurgy and Engineering [Denver, Colorado] September 29, 1910 (Vol. LXII, 1600).

For more on the fascinating life and times of “Col.” William C. Greene, the best book is Colonel Greene and the Copper Skyrocket; The Spectacular Rise and Fall of William Cornell Greene, Copper King, Cattle Baron and Promoter, by Charles Leland Sonnichsen (1974). I recall KvonM recommending it when it was published.

Last edited:

NP

NP