Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- #1

Thread Owner

THE LOST GUN-SIGHT MINE.

from The Miner’s Guide; A Ready Handbook for the Prospector and Miner, by Horace J. West (Los Angeles: Second Edition – 1925)

This perhaps has led to as many deaths as all of the other lost mining properties together, for the reason that the Lost Gun-sight Mine has been located by its original discoverer somewhere in Death Valley, the dread sink of waterless waste that has been the basis of many a blood-curdling yarn of fabulous discoveries that have never been made public and of strange disappearances through a period of forty years [from circa 1920].

This discovery, unlike most of the other lost mine discoveries, had silver of almost virgin purity as the basis of its worth instead of gold. Nor was the discovery a little ledge, a few veins or massive nuggets. It was a solid mountain of black sulphurets of silver located somewhere in the southern portion of the Panamint Range, and had its origin in the tale brought to the Southern California towns by a band of immigrants who had nearly lost their lives from lack of water in the valley of perpetual despair.

One of their number, Joseph Bennett, was the first to reach the confines of that mysterious waste which stretches in length for one hundred and twenty-eight miles, and at its widest portion for twenty-seven miles, void of nearly every semblance of vegetation and containing but two or three springs of water.

Bennett was more adventurous than others of the party of immigrants and acted as trail-blazer. He wandered sometimes a day in advance of the others on the trip westward. And one day he wandered so far ahead that his water gave out and he was unable to retrace his steps. Nearly famished, he chased from one phantom spring to another, finally coming to a real one, which since that time has been known as Bennett’s Hole and which proved the salvation of many a prospector.

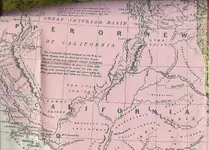

A New Map of Texas Oregon and California (1846)

From there, after a day’s rest, Bennett made his way back into the range that came to the edge of the desert and circled with them some twenty miles to the westward, finding eventually a good spring of water. There were a few trees, live-oaks and willows, surrounding the spring, and, suffering still from the days of his ceaseless chase for water, he remained there a week. It was on one of these days that he happened to notice the metallic quality of some of the rock that surrounded him.

He made closer investigation, and although lacking all sense of the prospector and with no mining experience to tell him right, he realized that he had stumbled upon a wonder deposit of silver. The croppings came from a number of ledges and were all black with the corrosion of some sulphate. He broke off a number of large chunks of the metal and then started again on his journey to a place of civilization.

That journey, like many others of similar character, has gone down in history as one of fearful hardships, despair of ever arriving at a goal, and, during the final days of struggle, despair of ever finding water or food again. He was discovered by another prospector and brought into Needles more dead than alive, but still clinging to the silver that he had found.

For weeks he was insane, and when he finally came back to his senses he had lost all reckoning of distanced traversed or the exact locality of the immense silver deposit. When he had sufficiently recovered he started out to relocate the property. He failed a second and third time in his endeavor.

On the last two trips he made he carried with him a gun on which he placed his faith for unerring aim. He purchased the gun, an old rifle, from a miner who was down and out, and the weapon having no sight, he had the blacksmith fashion one from the silver ore which he carried. With this he wandered through mountains and valley after valley, hoping to be able to shoot into the ledge which contained the original metal of the sight. He failed, as did his friends who attempted to follow his directions.

A record of a score of deaths has been laid to this discovery because of the men who have started out for it and have never returned, leaving perhaps their bones to dry and blow away on the parched sands of Death Valley.

to be continued…Next – “Lost Mine of Arizona.” That will end “The Lost Mine of the Desert” Series.

--- o0o ---

At the very bottom of this page is a

“Tip Jar.”

If you enjoyed reading this yarn, please toss a buck or two

Into the kitty and help keep TreasureNet on the ‘Web!

[Please end it with nine cents.]

“Tip Jar.”

If you enjoyed reading this yarn, please toss a buck or two

Into the kitty and help keep TreasureNet on the ‘Web!

[Please end it with nine cents.]

--- o0o ---

Further Reading

The saga of the Gunsight “Lead” is one of the great Lost Mine stories of the American West. It is grounded in fact more than almost all the others – due to a combination of extant reliable first-hand accounts and the fact that Death Valley and its surrounding country have proven to be rich in both gold and silver.

Mr. West’s version of this yarn is rather brief. And at odds with several of the generally accepted versions. Once again, when the author stays from Southern California to the Amargosa Desert he leaves his local knowledge behind, like the trail of grandfather clocks and rocking chairs abandoned by an immigrant wagon train.

Fortunately we have Henry G. Hanks’ account from Borax Deposits of California and Nevada, published in the Third Annual Report of the State Mineralogist of California (1883). Most of it was reprinted in Harold O. Weight’s excellent work 20 Mule Team Days in Death Valley (1955). I quote at length from that Report to provide the reader with a more complete version than Mr. West’s. The careful student will want to refer to the original.

Death Valley takes its name from the circumstances of a company of emigrants entering it on their way from Salt Lake to California in the year 1850. Very little was known then of the passes through the mountains, and this party made the fatal mistake of attempting a more direct pass than the well known emigrant road. They little knew the dreadful experience they were destined to make, or the sufferings they were to endure.

The valley was to them a cul de sac, a region wholly unexplored. While seeking an outlet, they experienced dangers and difficulties unexpected and almost insurmountable. Finding it impossible to take their wagons over the mountains they abandoned them, and while some of the party climbed the rugged and roadless passes, others, seeking water, miserably perished. Those who escaped, in relating the horrors of the journey, told romantic stories of mines, of gold and silver, all generally exaggerated, but which have induced others to visit the locality in search of the mythical mines described.

Bennett, one of the emigrants, drank at a running stream of clear water, on the pebbly bottom of which he said he saw lumps of glittering gold; an unlikely story, for gold is seldom if ever seen under such circumstances. Another said he found a piece of white metal which he took with him, not knowing its nature or value until months after, while in Los Angeles, he required a new gunsight and delivering the metal to the gunsmith with an order, was informed that it was pure silver. [Mr. Weight pointed out it was probably John Goller and not Asabel Bennett.]

This story, more absurd, if possible, than the first, has caused a number of parties to visit and explore Death Valley in search of the “gunsight lead,” which has never been found. While these expeditions have generally ended in disappointment they have led to a knowledge of the country, the discovery of mines of antimony [the “Christmas Gift”], silver, and gold, of unknown value, and now of not less importance borax fields. The discovery of Coso, Slate Range, Owens’ Valley, Panamint, Argus, Telescope, Calico, and other mining districts are the results of these expeditions.

…

The emigrant party has been mentioned before, and the reputed discovery of rich mines of gold and silver by them.

After the discovery of the Comstock silver mine in 1858, these old forgotten stories were revived, and in the hope of finding valuable mines, exploring parties were organized to thoroughly prospect the country.

In May 1860 a party of 15 men headed by Dr. Darwin French, left Butte County in search for the Gunsight lead.

They journeyed via Visalia, South Fork of Kern River, Walker’s Pass, Indian Wells, and Little Owens’ Lake thence easterly, to Hot Mud Springs, to Crystal Springs, Granite Springs, Darwin Canyon, and across the head of Panamint Valley, thence by a rocky pass to a camp in Death Valley, where the emigrants left their wagons, 25 miles a little west of north from Furnace Creek as before stated. The party returned by the way they came, without success as to the discovery they hoped to make. They became satisfied that a pass they came through was the same by which led them to name it “Towne’s Pass.” Among the party were Dr. Darwin French, James Hitchens, N.H. Farley, Dr. W.B. Lilley, Capt. Robert Bailey and J. Lilliard. Darwin [Spring?] and Darwin Canyon, were named after French.

Ghost Camp of the Forty-Niners

October 1, 1860, Dr. S.C. George, Dr. W.B. Lilley, T.J. Henderson, Stephen Gregg, Moses Thayer, and J.r. Hill, organized to search fo the Gunsight lead. They followed the same general route of the French party, remained at the Emigrant Camp for some time, prospecting the hills in every direction. At a locality two miles distant from the camp, “Hunter’s Point,” they found water by digging a few feet, and 12 miles distant a fine spring of good water. Although 10 years had passed, the tracks of the men, women and children were distinctly seen, as fresh as if newly made; the irons of the wagons were where they had been left. The remains of the ox yokes were seen, which had been laid out for use on the following day, with the chains extended o the ground in front of each wagon, showing the number of oxen to each, and traces of the old camp fires were plainly seen…

While prospecting the hills, Dr. George and Dr. Thayer found the bones of white men within 300 yards of a spring of good water, believed to be the emigrant party. The returning party followed an Indian trail to Hunter’s Point, and through a mountain pass to Wild Rose Spring, which they named, and at which they camped for two weeks, while prospecting in Panamint Valley. On Christmas Day they discovered a mine of antimony, three miles from Wild Rose, which they named the “Christmas Gift.”

Mr. Hanks makes a very important point that cannot be stressed enough. While we may debate the accurate butcher’s bill Death Valley has charged, there can be no doubt it is a very dangerous locale.

The climate of Death Valley is most distressing to the human body. While in Winter it is quite pleasant, in Summer is it almost unbearable. The dryness of the air is so excessive that moisture is withdrawn from the body faster than it can be supplied through the system. From this cause frequent cases of death have occurred when water was plenty, but could not be drank fast enough to supply the drain caused by the dessicative power of the dry hot air.

The Lost Gunsight Lead hunter should start with Death Valley in ’49 by William Lewis Manly (1894). It is readily available in any number of editions – and it is the foundation for any library on the subject of Death Valley. It is one of the great books about the America West. Of more utility for the Lost Gunsight hunter is The Jayhawkers’ Oath and Other Sketches, edited by Arthur Woodward (1949). It collects many of Mr. Manley’s newspaper articles about the mine – and it includes John Colton’s essential “The Death Valley Mines” (1895).

I highly recommend William Caruthers’ Loafing Along Death Valley Trails; A Personal Narrative of People and Places (1951). It includes a Lost Mines chapter – however, the whole book is a treasure.

William Manly, author of ‘Death Valley in Forty-Nine’ also tried but gained only another tragic experience and came nearer losing his life than he did with the Forty-Niners. Lost and without water and beaten to his knees, he was deserted by companions and escaped death by a miracle. How many have lost their lives trying to find the Gunsight no one knows. There are scores of sunken mounds on lonely mesas which an old timer will explain tersely: ‘He was looking for the Gunsight.’”

Harry Sinclair Drago presented a somewhat confusing version in his Lost Bonanzas; Tales of the Legendary Lost Mines of the American West (1966). Death Valley has not been kind to this otherwise generally reliable scribe.

He terms Harold O. Weight “the best of all Death Valley chroniclers.” This is quite true. Lost Mines of Death Valley (Twentynine Palms, California: 1953; revised and enlarged 1961 & again in 1970) is the single best work ever published on Death Valley’s lost mines and hidden treasures. The third edition is the best and most complete. I cannot recommend this book highly enough. If you were to only consult one book on the Lost Gunsight Lead, I would suggest it be Mr. Weight’s.

C.B. Glasscock’s Gold in Them Hills (1932) includes this brief account in the chapter “Lost Mines and Desert Thirst:”

Legend recites that the Gunsight was found originally in the Panamint Mountains on the western side of Death Valley by three Mormon emigrants seeking a way out of the valley for their main party, perishing at Bitter Springs. One man knocked the sight off his gun while climbing a cliff. Later he made a temporary sight from some malleable metal chipped from the ledge. When he reached civilization this sight was found to be virgin silver. Hundreds of men have searched in vain for that mine for three-quarters of a century [written in 1932] , and are still searching, and dying in the search. And there are a dozen others, less famous but equally dangerous.

Mr. Glasscock’s Here’s Death Valley (1940) includes considerably more information, including expeditions lead by Dr. Darwin French, and the George and Ives excursions after this elusive prospect.

A very valuable addition to Lost Gunsight lore is “Gunsight – On Target!” by George Koenig (True West, Vol. 18, No. 6 – Whole No. 94; July-August 1969). Mr. Koenig combines first-rate research with experience on the ground. Anything he writes about Death Valley is well worth reading.

Clarence E. Wager wrote an autobiographical account of searching for the Lost Gunsight in a Flivver during the 1920’s. “Death Valley Silver” was first published in Frontier Times (Vol. 33, No. 1 – Winter 1957-58); Reprinted in GOLD! 4th Edition (Vol. 3, No. 2 – Bi-Annual 1971). This is well worth reading.

Most versions of the Lost Gunsight story dwell on the astonishing number of prospectors who have died in the search. Indeed, while Mr. Hanks was obviously skeptical regarding the mineral wealth to be found in Death Valley, he had no trouble believing large number of searchers were lost in the hunt. To swallow whole his version – and many others - the floor of Death Valley must be carpeted with whitened bones like the sands of Arabia Deserta after the loss of King Cambyses II’s army.

Afar more sober note is struck by Daniel Cronkhite in his well-researched Death Valley’s Victims; A Descriptive Chronology 1849-1966 (1968). First he notes that a single Forty-Niner perished in their desert crossing: Capt. Culverwell.

After the emigrants got out of Death Valley and to the Coast, very little, if anything, was heard of the place until 1861. Mexicans had been mining in the region for several years (some say as early as 1844) but this wasn’t considered earth shaking news to most. The lost Gunsight Mine is a well known topic to history students (an outcropping of highgrade silver was found by one of the Forty-Niners in the Panamint Mountains) and some wanted to return and find the source. Thus Death Valley’s period of mining activity was launched.

Several attempts were made by different parties in 1861, but most were in vain. It was one of these groups, headed by S.G. George, which met a violent end. They found some promising minerals in Wildrose Canyon, and went so far as to run a tunnel, but Indians resenting the invasion of their meager hunting grounds, killed George and his party of three. The tunnel they had constructed became their grave.

One of the reasons the story of the Lost Gunsight is compelling is the number of first-hand accounts – from both those who found it and those who sought it. One classic is George Miller’s “A Trip to Death Valley,” which appeared in the Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California (1919). I recommend it highly.

Ed Bartholomew, writing as Jesse E. Rascoe, provided an account of the Lost Gunsight in Some Western Trails (1973). This is based on an October 26, 1886, article in the Wichita, Kansas, Eagle. That paper reprinted a report penned by W.E. Koop, the Los Angeles correspondent for the New York Sun where it apparently first appeared. In the 19h Century, before the wire services were established, it was quite common for papers to reprint articles from other newspapers.

The entire article is reproduced in facsimile at the end of “Rascoe’s” Southern California Treasures (1969). This also includes a brief version of the Lost Gunsight and Lost Breyfogle stories.

The book on single-blanket, jackass prospectors is Herman W. Albert’s Odyssey of a Desert Prospector (1967). Several excellent prospectors’ stories are available in Richard Lingenfelter’s Death Valley Lore; Classic Tales of Fantasy, Adventure, and Mystery (1988). These include “Prospecting Death Valley in Summer,” by Paul DeLaney; “ “Half a Century Chasing Rainbows,” by Frank “Shorty” Harris; and the very interesting “Breyfogle’s Lost Ledge,” by Standish Road – a rare first-hand account.

--- o0o ---

This is Part VIII of the Lost Mines of the Desert series. Part I was posted December 26, 2008. Part II – “The Lost Arch” Diggings went up January 3, 2009. Part III – The Peg-Leg Mine; Or, the God of Fury’s Black Gold Nuggets, was made available January 11, 2009, and may be found under the Lost Peg Leg Mine topic. Part IV – The Lost Papuan Diggings – again saw the light of day on January 19, 2009. Part V – The Lost Dutch-Oven Mine – was posted January 27, 2009. Part VI – The Lost Breyfoggle [sic] appeared February 8, 2009. After a too-lengthy hiatus Part VII – The Goler Placer Diggings – came out on April 26, 2011.

Once this series has been completed, I am considering collecting all these stories, along with The Lost Tub Placer yarn that will not be reprinted on the Treasure Net Forum, into a booklet for ready reference and convenient reading. If you would like to be notified when that is done, please send me a PM.

= 30 =