Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- Dec 4, 2008

- 4,567

- 3,944

Lost Gold Mines of the American West

By Charles Michelson

Charles Michelson was born in Virginia City, Nevada, in 1869. He ran away from his Comstock Lode home thirteen years later, eventually becoming a newspaper reporter for William Randolph Hurst’s San Francisco Examiner. In the tradition of another Virginia City reporter, Samuel Clements, Michelson was more concerned with writing a good story than he was in presenting his readers with facts. He described his time as a San Francisco police reporter as writing about “a thousand interesting incidents, some of which really happened.”

Hurst sent Michelson to Cuba to cover the Spanish American War. According to legend, Hurst wanted a war so he could sell newspapers. After the explosion of the USS Maine in the harbor of Havana, Hurst quickly and daily blamed it on the Spanish colonial government. Hurst dispatched Frederic Remington to Cuba as a war artist. Remington protested there was no war. Hurst, according to the story, replied “You supply the pictures. I’ll supply the war.”

In Cuba Michelson was captured as a spy. Released, he found his way to Hollywood and became a screen writer. Then he moved to Washington, DC, as a political reporter and newspaper bureau chief. In the 1930’s, Michelson became Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “press agent.” His detractors claimed that in his political work he showed the same cavalier attitude towards facts that he’d demonstrated as a newspaper reporter. Michelson has been credited with coining the name “Hoovervilles” for the shanty towns that sprung up during the Great Depression.

Michelson’s autobiography The Ghost Talks was published in 1944.

The following account was published in 1901. It draws on Michelson’s own frontier experiences – and his proclivity to never miss a good story.

On a hilltop in southern California, in sight of the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad, there is gold enough to satisfy the most avaricious man that ever loved the yellow god, ready to the hand of any one who will pick it up. It lies there in lumps, uncovered on the ground, much of it pure enough to be exchanged for coin at the mint. No fierce savages bar the way to it; no legal prohibitions make it inaccessible; it is not on any Indian reservation or other preserve whence any man might be prevented from taking it.

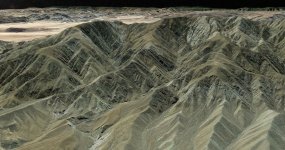

To make it easier for a seeker after this gold, I am at liberty to state that it lies between latitude 32:30 and 34, not further east than 115:30, nor further west than 117. In order that the hunter may identify the place, I can further inform him that the scattered nuggets are on the rounding peak of the highest of three hills, none of which is particularly hard to climb. To show the accessibility of the peak and the presence of the gold on its summit, it is sufficient to say that the treasure place has been visited at different times during the last fifty years by at least four people, one of them a woman. Each brought away as many bits of gold as could be conveniently carried, and told of the great quantity that remains. I am informed that specimens of these nuggets are on exhibition in various mining museums in the West.

It is possible to be still more explicit as to the locality. From the gold strewn hilltop the smoke of the railroad trains can be seen as they pass near Salton station. To reach the spot, one can go west from Fort Yuma on the old Los Angeles trail, which approximately follows the Mexican line, to a point near where it turns north. From this point the way lies a little to the eastward of Warner's Pass. If he is on the right road, the three peaks will loom before him; let him climb the highest one, and if he finds beneath his feet pebbles and cobbles of dark gold, then he may know he has found the lost Pegleg mine, the search for which has cost as many lives as most battles, and suffering and disappointment beyond reckoning.

The Pegleg is the greatest of all the mines which, having once disclosed their richness to man, have faded from his ken. It is in no sense a myth, like so many similar subjects of mining camp lore. There is an enormously rich deposit of gold somewhere in the fiery desolation of those southern mountains; gold from it has purchased articles of use or pleasure; some of its product has passed into the coin of the country. Its existence is proved by evidence that would be received in any court. Its history is a series of tragedies.

Most of the lost mines, real or chimerical, have a history of the same sort, particularly in that strange, sinister country where the deserts are beneath the level of the sea, and the rotten crust of the earth lets the unwary traveler down into a lye strong enough to eat shoe leather; where the mountains pierce the sky, but have not enough soil on their slopes to give a hold to the hardiest of desert shrubs.

MEN WHO HAVE SEEN THE PEGLEG

The Pegleg first came to the knowledge of men in the early fifties. A one legged frontier roustabout named Smith, coming from Yuma to Los Angeles, attempted a short cut across the desert and over the hills instead of following the trail, which winds its cautious way from water hole to water hole along the frontier of Mexico and finally turns north almost at a right angle to go up by Warner's Pass. Smith lost his bearings, and climbed a hill to search the horizon for a landmark. The hill was curiously sprinkled with dark, heavy lumps, which Smith did not recognize—people were not looking for gold in that country then. He took several fragments of convenient size to put with his snake rattles, arrow heads, and similar frontier curios, and went on to Los Angeles. Some years later he showed his collection to a man who knew gold. It was much darker than gold is usually, probably because of the presence of some natural alloy; but the Los Angelanos attributed the color to the gold's having been exposed to the sun, and the phrase "sun burned gold" became engrafted on the language of the Western miners.

Pegleg Smith, never an intellectual giant, promptly went crazy on learning of his escape from great wealth. Various people beset him during his lucid intervals, and to them he told all he could. Every man who thought he might find the place started out secretly to look for it, and for several years the hills between Warner's and Yuma were full of them. The skeletons of these searchers continue to be found to this day.

The search for Pegleg's find had pretty well subsided when a discharged soldier from Fort Yuma came into San Bernardino with a lot of dark nuggets. He knew what they were, and was willing to tell where he found them. He described the three peaks, and how he came to climb the gold crowned one. He went on a wild spree to celebrate his good luck, and would not guide anybody to the place until he had spent all his gold. At last he started out with half a dozen companions, well equipped with mule teams. Men not permitted to join the expedition trailed it far enough to learn that it did not go by Warner's Pass and Carriso Springs, which would have been the route had the soldier's account been a truthful one; but the trail was lost to the east of Warner's. Five years later prospectors ran across the skeletons of men and animals, in the foothills of the Cuyamaca Mountains, thirty miles southwest of Salton. According to one story, there were but two skeletons; but a man who said he helped bury the bones told me that a few rods away from the death camp he found a third, with a bullet hole in the skull.

One man is as competent as another to reconstruct the tragedy of the Cuyamaca foothills from these indications. At all events, neither the discharged soldier nor any of his companions ever appears again in the history of the Pegleg bonanza.

The mine next caused excitement in the days of the railroad building. The line was being run north from Yuma, and the rails had been laid to what is now Salton station. Suddenly there appeared to the track layers a squaw from the Indian reservation near the head of the Rio San Luis Rey. She fell exhausted as she came near, her tongue bursting from her mouth with thirst. They gave her water and revived her. In a handkerchief she had wrapped probably two pounds of the dark gold, a sight of which is enough to set any community in southern California in a frenzy. She explained that she and her buck were traveling to the Cocopah reservation, and that their canteen had leaked. In searching for a water hole they lost their way, and struck for high ground to look about. After two days' wandering they found the gold on the top of one of three hills, from which they caught sight of the smoke of the construction train. Her man, she said, had given out and died before they had gained the track.

The Indians of California know what gold is now, and the squaw knew the value of her find. She would not point out the treasure peak or even indicate its direction, and the various members of the section gang said they had seen her approaching the camp by utterly divergent paths. She had probably circled the camp, Indian fashion, before coming in. On this slight clue, most of the gang quit work and started for the hills, and the scattered graveyard of the Pegleg was further augmented.

The squaw went back among her own people and was never identified, though many of those who saw her on the desert tried to find her again.

The last trace of the Pegleg that Californians tell about is in connection with a Mexican cowboy on Warner's ranch, with, after being absent without permission for several days, suddenly reappeared with a quantity of the dark gold. For a time he was the most gorgeous thing in San Bernardino County. His saddle was a miracle of carved leather and silver; his sombrero weighed a pound and a half, so thickly was it incrusted with silver braid; he rode the finest horse in the Southwest, played the limit in every monte and faro bank within range, and made love to all the girls that would listen to him. Whenever his wealth ran low he would disappear for two or three days and return with more of the gold. A hundred men tried to trail him, but he took care of his tracks and nobody ever learned where he went. When he was cut to pieces in a knife duel with a rival, he had on deposit at Warner's four thousand dollars in nuggets and coarse gold, but he left no word of its source.

As usual, the country generally started out to search. Only Tom Carver [sic - should be "Cover"], former sheriff, had anything to go on. Once, while hunting horse thieves, he had met the auriferous Mexican in the hills. With a companion, Carver sought the Pegleg, taking the place where he met the cowboy for a starting point. One day he left his friend in a buckboard on the desert, while he went up a little canyon on foot. He never came back, nor was any trace of his body found, though it was faithfully searched for.

The story of the Pegleg is, with few variations, the story of nearly all the lost mines in this little corner of the United States, which holds more of them than all the rest of the country combined.

Munsey’s Magazine [Vol. XXVI, No. 3] – December 1901

In the May 1969 issue of Desert Magazine is the article Fifty Years on the Pegleg Trail, by Walter Ford. It is the story of Henry E.W. Wilson, an English immigrant, who spent five decades in the searing heat of the Borrego Badlands, seeking Pegleg’s lost gold nuggets, and other legendary bonanzas supposed to be located in California’s Imperial County.

After hearing an Old Timer recount the Pegleg story, Wilson read in “a popular magazine of the time” the “full account” of the Pegleg saga. Yes, the spell of the lost Pegleg nuggets had been cast – by the article quoted above.

Information on Charles Michelson was found in https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-man-who-went-full-trump-for-fdr. At the end of the article is a telling quote from Michelson: “Ours is the government that suits us.”

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

By Charles Michelson

Charles Michelson was born in Virginia City, Nevada, in 1869. He ran away from his Comstock Lode home thirteen years later, eventually becoming a newspaper reporter for William Randolph Hurst’s San Francisco Examiner. In the tradition of another Virginia City reporter, Samuel Clements, Michelson was more concerned with writing a good story than he was in presenting his readers with facts. He described his time as a San Francisco police reporter as writing about “a thousand interesting incidents, some of which really happened.”

Hurst sent Michelson to Cuba to cover the Spanish American War. According to legend, Hurst wanted a war so he could sell newspapers. After the explosion of the USS Maine in the harbor of Havana, Hurst quickly and daily blamed it on the Spanish colonial government. Hurst dispatched Frederic Remington to Cuba as a war artist. Remington protested there was no war. Hurst, according to the story, replied “You supply the pictures. I’ll supply the war.”

In Cuba Michelson was captured as a spy. Released, he found his way to Hollywood and became a screen writer. Then he moved to Washington, DC, as a political reporter and newspaper bureau chief. In the 1930’s, Michelson became Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “press agent.” His detractors claimed that in his political work he showed the same cavalier attitude towards facts that he’d demonstrated as a newspaper reporter. Michelson has been credited with coining the name “Hoovervilles” for the shanty towns that sprung up during the Great Depression.

Michelson’s autobiography The Ghost Talks was published in 1944.

The following account was published in 1901. It draws on Michelson’s own frontier experiences – and his proclivity to never miss a good story.

On a hilltop in southern California, in sight of the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad, there is gold enough to satisfy the most avaricious man that ever loved the yellow god, ready to the hand of any one who will pick it up. It lies there in lumps, uncovered on the ground, much of it pure enough to be exchanged for coin at the mint. No fierce savages bar the way to it; no legal prohibitions make it inaccessible; it is not on any Indian reservation or other preserve whence any man might be prevented from taking it.

To make it easier for a seeker after this gold, I am at liberty to state that it lies between latitude 32:30 and 34, not further east than 115:30, nor further west than 117. In order that the hunter may identify the place, I can further inform him that the scattered nuggets are on the rounding peak of the highest of three hills, none of which is particularly hard to climb. To show the accessibility of the peak and the presence of the gold on its summit, it is sufficient to say that the treasure place has been visited at different times during the last fifty years by at least four people, one of them a woman. Each brought away as many bits of gold as could be conveniently carried, and told of the great quantity that remains. I am informed that specimens of these nuggets are on exhibition in various mining museums in the West.

It is possible to be still more explicit as to the locality. From the gold strewn hilltop the smoke of the railroad trains can be seen as they pass near Salton station. To reach the spot, one can go west from Fort Yuma on the old Los Angeles trail, which approximately follows the Mexican line, to a point near where it turns north. From this point the way lies a little to the eastward of Warner's Pass. If he is on the right road, the three peaks will loom before him; let him climb the highest one, and if he finds beneath his feet pebbles and cobbles of dark gold, then he may know he has found the lost Pegleg mine, the search for which has cost as many lives as most battles, and suffering and disappointment beyond reckoning.

The Pegleg is the greatest of all the mines which, having once disclosed their richness to man, have faded from his ken. It is in no sense a myth, like so many similar subjects of mining camp lore. There is an enormously rich deposit of gold somewhere in the fiery desolation of those southern mountains; gold from it has purchased articles of use or pleasure; some of its product has passed into the coin of the country. Its existence is proved by evidence that would be received in any court. Its history is a series of tragedies.

Most of the lost mines, real or chimerical, have a history of the same sort, particularly in that strange, sinister country where the deserts are beneath the level of the sea, and the rotten crust of the earth lets the unwary traveler down into a lye strong enough to eat shoe leather; where the mountains pierce the sky, but have not enough soil on their slopes to give a hold to the hardiest of desert shrubs.

MEN WHO HAVE SEEN THE PEGLEG

The Pegleg first came to the knowledge of men in the early fifties. A one legged frontier roustabout named Smith, coming from Yuma to Los Angeles, attempted a short cut across the desert and over the hills instead of following the trail, which winds its cautious way from water hole to water hole along the frontier of Mexico and finally turns north almost at a right angle to go up by Warner's Pass. Smith lost his bearings, and climbed a hill to search the horizon for a landmark. The hill was curiously sprinkled with dark, heavy lumps, which Smith did not recognize—people were not looking for gold in that country then. He took several fragments of convenient size to put with his snake rattles, arrow heads, and similar frontier curios, and went on to Los Angeles. Some years later he showed his collection to a man who knew gold. It was much darker than gold is usually, probably because of the presence of some natural alloy; but the Los Angelanos attributed the color to the gold's having been exposed to the sun, and the phrase "sun burned gold" became engrafted on the language of the Western miners.

Pegleg Smith, never an intellectual giant, promptly went crazy on learning of his escape from great wealth. Various people beset him during his lucid intervals, and to them he told all he could. Every man who thought he might find the place started out secretly to look for it, and for several years the hills between Warner's and Yuma were full of them. The skeletons of these searchers continue to be found to this day.

The search for Pegleg's find had pretty well subsided when a discharged soldier from Fort Yuma came into San Bernardino with a lot of dark nuggets. He knew what they were, and was willing to tell where he found them. He described the three peaks, and how he came to climb the gold crowned one. He went on a wild spree to celebrate his good luck, and would not guide anybody to the place until he had spent all his gold. At last he started out with half a dozen companions, well equipped with mule teams. Men not permitted to join the expedition trailed it far enough to learn that it did not go by Warner's Pass and Carriso Springs, which would have been the route had the soldier's account been a truthful one; but the trail was lost to the east of Warner's. Five years later prospectors ran across the skeletons of men and animals, in the foothills of the Cuyamaca Mountains, thirty miles southwest of Salton. According to one story, there were but two skeletons; but a man who said he helped bury the bones told me that a few rods away from the death camp he found a third, with a bullet hole in the skull.

One man is as competent as another to reconstruct the tragedy of the Cuyamaca foothills from these indications. At all events, neither the discharged soldier nor any of his companions ever appears again in the history of the Pegleg bonanza.

The mine next caused excitement in the days of the railroad building. The line was being run north from Yuma, and the rails had been laid to what is now Salton station. Suddenly there appeared to the track layers a squaw from the Indian reservation near the head of the Rio San Luis Rey. She fell exhausted as she came near, her tongue bursting from her mouth with thirst. They gave her water and revived her. In a handkerchief she had wrapped probably two pounds of the dark gold, a sight of which is enough to set any community in southern California in a frenzy. She explained that she and her buck were traveling to the Cocopah reservation, and that their canteen had leaked. In searching for a water hole they lost their way, and struck for high ground to look about. After two days' wandering they found the gold on the top of one of three hills, from which they caught sight of the smoke of the construction train. Her man, she said, had given out and died before they had gained the track.

The Indians of California know what gold is now, and the squaw knew the value of her find. She would not point out the treasure peak or even indicate its direction, and the various members of the section gang said they had seen her approaching the camp by utterly divergent paths. She had probably circled the camp, Indian fashion, before coming in. On this slight clue, most of the gang quit work and started for the hills, and the scattered graveyard of the Pegleg was further augmented.

The squaw went back among her own people and was never identified, though many of those who saw her on the desert tried to find her again.

The last trace of the Pegleg that Californians tell about is in connection with a Mexican cowboy on Warner's ranch, with, after being absent without permission for several days, suddenly reappeared with a quantity of the dark gold. For a time he was the most gorgeous thing in San Bernardino County. His saddle was a miracle of carved leather and silver; his sombrero weighed a pound and a half, so thickly was it incrusted with silver braid; he rode the finest horse in the Southwest, played the limit in every monte and faro bank within range, and made love to all the girls that would listen to him. Whenever his wealth ran low he would disappear for two or three days and return with more of the gold. A hundred men tried to trail him, but he took care of his tracks and nobody ever learned where he went. When he was cut to pieces in a knife duel with a rival, he had on deposit at Warner's four thousand dollars in nuggets and coarse gold, but he left no word of its source.

As usual, the country generally started out to search. Only Tom Carver [sic - should be "Cover"], former sheriff, had anything to go on. Once, while hunting horse thieves, he had met the auriferous Mexican in the hills. With a companion, Carver sought the Pegleg, taking the place where he met the cowboy for a starting point. One day he left his friend in a buckboard on the desert, while he went up a little canyon on foot. He never came back, nor was any trace of his body found, though it was faithfully searched for.

The story of the Pegleg is, with few variations, the story of nearly all the lost mines in this little corner of the United States, which holds more of them than all the rest of the country combined.

Munsey’s Magazine [Vol. XXVI, No. 3] – December 1901

-------- o0o --------

In the May 1969 issue of Desert Magazine is the article Fifty Years on the Pegleg Trail, by Walter Ford. It is the story of Henry E.W. Wilson, an English immigrant, who spent five decades in the searing heat of the Borrego Badlands, seeking Pegleg’s lost gold nuggets, and other legendary bonanzas supposed to be located in California’s Imperial County.

After hearing an Old Timer recount the Pegleg story, Wilson read in “a popular magazine of the time” the “full account” of the Pegleg saga. Yes, the spell of the lost Pegleg nuggets had been cast – by the article quoted above.

-------- o0o --------

Information on Charles Michelson was found in https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-man-who-went-full-trump-for-fdr. At the end of the article is a telling quote from Michelson: “Ours is the government that suits us.”

Good luck to all,

The Old Bookaroo

Amazon Forum Fav 👍

Last edited: