Old Bookaroo

Silver Member

- #1

Thread Owner

THE PEG-LEG MINE;

OR, THE GOD OF FURY’S BLACK GOLD NUGGETS

OR, THE GOD OF FURY’S BLACK GOLD NUGGETS

from The Miner’s Guide; A Ready Handbook for the Prospector and Miner, by Horace J. West (Los Angeles: Second Edition – 1925)

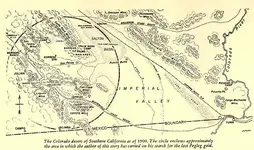

Just about twelve years ago [that is, circa 1909 – 1913] the Great Southwest was awakened by the possibility of the relocation of the widely known Peg-Leg Mine. The Southern Pacific Railroad was doing considerable work through Imperial valley, a valley which five years previously was one of the hottest and most forsaken deserts on the American Continent, but which, with the coming of water through the extensive irrigation system of the Government, has grown to be one of the brightest garden spots in the world.

The only human beings who ever ventured into the valley before the bringing-in of water were the prospectors and then the engineers and their crews of hardly lineman, rodmen and assistants who were surveying roads, lateral canals for subsequent irrigation, and similar work. A large crew was stationed between Ogeby and Salton, rebuilding much of the track. They were near a water-place named Glamis when the incident occurred which sent many of them scurrying from their work into the mountain ranges in a vain effort to find the wonderful property that they knew must exist.

While driving the work along slowly under the brazen sun and amid the occasional sand-clouds stirred up by a slight breeze from the mountains, a figure appeared in the distance, just a vague, traceable figure, slowly and wearily pushing along through the clogging sands. As it approached, it resolved itself into a wandering Indian squaw, apparently half dead from lack of water, who, without going near the work-men, passed on to the tank and there started to drink from the small open trough.

Thinking to assist her when she seemed about to drop into a heap from nothing more than exhaustion of her toilsome journey, several of the men started in her direction. She saw them coming. With an effort she arose and made off with all speed down the track in the opposite direction.

She was followed for a distance until she turned off into the desert again, and, having no great interest in a single squaw, the men returned. On arriving at the water-tank they discovered an old piece of blanket securely tied in a knot. On opening it they found a lot of black pieces of metal, which under a knife revealed pure gold of darkest hue. They were nuggets, dozens of them, varying in size from smaller than a dime to the size of an English walnut, and all of them black.

Hastily the men tried to follow the squaw, but by this time she had disappeared in the same range of mountains to the north from which she had been seen to emerge. When the finders of the gold had an opportunity of having the metal assayed and valued, they were brought to the realization of the worth of the discovery. The little pack had contained more than two thousand dollars’ worth of property.

Such a find could not help starting a search and creating talk, and it was but a short time before a number of old miners were on the scene. They knew the value of the black gold and also that in this section, buried far from observation or generally overlooked by prospectors who had been through the ranges before, lay the old Peg-Leg Mine with its fabled wealth. There was a stampede from the camp, which did not last long on account of the hardships the searchers had to face.

Only in the northwestern part of the range is there any living water, the Salvation Springs. Other portions of the range contain huge natural tanks in the mountains, which at that time were discovered in all but one or two instances to be dried up. As a result, only a few hardy prospectors were steady in their search, which had its original inception in 1853 when “Peg-Leg” Smith wandered into Mojave with nearly ten thousand dollars’ worth of black nuggets in his possession.

Pegleg Smith in San Francisco - 1861; from Hutchings' California Magazine

The day he pulled into the mining camp with its three saloons and two stores, his lips were cracked and black, his tongue parched and swollen, and his hands almost bursting from the pressure of blood caused by long tramping. His mule had saved his life by half dragging him to the camp, which he would never have located alone.

For several days he lay abed, gripping the saddle-bags which had been brought into his rooms in one of the shacks that served as saloon and hotel. When he recovered consciousness and health, he opened the saddle-bags and satisfied the curiosity of the hundred or so prospectors who were working in the vicinity.

What they saw startled them. It was black gold. Nuggets, hundreds of them, as black as coal on the outside, but pure dull gold within. “Where did you get it?” was the question, and Smith tried to tell them, after securing from each of them a promise to share in the wealth should they find it.

According to his story, he had been living with the Yuma and the Cocopah Indians along the Colorado River for several years. Away from the river the land resolved itself into the driest, most desolate region imaginable, a region they seldom ventured into because of their dislike for their God of Fury, who overwhelmed them and buried them beneath the swirling sand-dunes when they sought the black pebbles.

They told stories of great treasures of yellow metal, but never ventured after it themselves. Smith, who had lost a leg while in an encounter with the Indians in crossing the plains, hoarded up all the stories, and after securing all information possible he decided on a trip to San Francisco to obtain a partner in his work. At that time the desert was not mapped, and it was a really hazardous undertaking for any man to attempt.

In this desolate region Smith lost his bearings. The fierce yellow sun, the dancing, jiggling heat-waves, the dust-flurries confused his direction. He finally climbed upon a black butte that stood near by and, arriving at is summit, probably fifteen hundred feet in the air, he attempted to locate his whereabouts.

“When I reached the top,” he told some of his friends, “I saw just a short distance away another butte of exactly the same height and type as the one on which I stood. It was connected with a low saddle, and the twin buttes were isolated from the main range. Finally I decided on the way I was to continue and started back down the hill to my mule, which had remained at the foot of the incline.

“I had tied the animal to a boulder in order to prevent it from breaking away and carrying off the only water-supply available for perhaps a week or more. Rather restless, the mule had stamped about and kicked up some good-sized pebbles that showed a strange glint where the hoofs had struck. Picking one of the black stones up, I pulled out my pocket-knife, scratched its surface and found that it was gold.”

It was a repetition of the old Oriental fable of the stranded Arab on the desert, who came across a sack of pearls when he sought figs and water. Smith was running short of food and water and could take only a few pounds on the already overcrowded mule, and these he placed in his saddle-bags, proceeding then on his route.

After he had recovered sufficiently, he started out to relocate his valuable property. Others had preceded him, and a number followed close along, hoping to be with him in the find. For days he wandered about, but the twin buttes had disappeared as if by the magic of an Aladdin’s lamp. He tried time and again, as did dozens of others, to locate this immensely wealthy find, a place, as he explained, where black gold lay strewn for blocks over the ground and looked like mere chunks of rock and lava pebbles.

He never succeeded in his quest. Nor has any one else. There have been many mints located in the district of the desert – the Mesquite Placer Diggings in the central part of Imperial County [in this copy (ours) is written after “Diggings,” and the next seven words crossed out] which have produced thousands and thousands, the Ogleby Diggings, the Salvation Springs Diggings, but not the mine of black volcanic-like gold. There are many black buttes in the country, but they, too, have failed to give up the secret of Peg-leg’s lost properties.

to be continued…Next – “The Lost Papuan Placer Diggings.”

Further Reading:

I think there should be little argument that the saga of Pegleg Smith’s lost black gold nuggets is the most likely to be true of all the great lost mine stories of the American West. For my money “Mr. Pegleg’s” letters to Desert Magazine are enough proof.

In Lost Bonanzas; Tales of the Legendary Lost Mines of the American West (New York: 1966), Harry Sinclair Drago provides a reliable, albeit quite skeptical, introduction to the Lost Peg Leg Smith story. It is important to keep in mind, however, that Mr. Drago didn’t have the benefit of the “Mr. Pegleg” revelations.

A very interesting account may be found in Famous Lost Mines of the Old West, edited by John H. Latham (Conroe, Texas: 1971), a collection of tales first published in the old True Treasure and Treasure World Magazines. Historian John M. Townley relies heavily on Alfred G. Humphreys’ graduate thesis, placing the possible location along a tributary of the Virgin River in Southern Nevada.

The classic account is Philip A. Bailey’s Golden Mirages; The Story of the Lost Pegleg Mine, the Legendary Three Gold Buttes, and Yarns of and by Those Who Know the Desert (New York: 1940 – reprinted several times). The 1971 “Special Commemorative Edition” (Ramona, California) is a handsome piece of work; but it may have been produced without the proper permission of the copyright holder.

Mr. Bailey’s admonition is worth listening to very carefully: “The yarns that make up this story may be taken in any mood one chooses; but the deserts must be taken seriously.”

The first biography of Thomas Pegleg Smith remains an outstanding work: The Lame Captain; The Life and Adventures of Pegleg Smith, by Sardis W. Templeton (Los Angeles: 1965) Great West and Indian Series XXXVIII. Because he was a member of the fur brigades, there is a great deal of well-documented and reliable Pegleg Smith history that treasure hunters should not overlook. An obvious place to begin would Leroy R.& Ann W. Hafen’s excellent books. And, unlike so many lost mine yarns, this one enjoys a considerable body of contemporary newspaper article documentation. Pegleg Smith appears to have been a colorful and therefore frequent favorite interview subject for many reporters.

The Pegleg Smith saga enjoyed an enthusiastic group of hunters during the 1950’s and 1960’s. Copies of Harry Oliver’s Desert Rat Scrapbook dealing with the subject are rather pricey today. Perhaps you will be able to locate the charming On the Trail of Pegleg Smith’s Gold; Legend and Fact Combined to Provide Fresh Clues to the Location of Pegleg Smith’s Famous Lost Mine by J. Wilson McKenney (Palm Desert, California: 1957).

The always-reliable Douglas McDonald offers the “Second Lost Pegleg Mine” in Nevada Lost Mines & Buried Treasures (Las Vegas, Nevada: 1981).

Anytime a serious treasure hunter can take advantage of the late Ed Bartholomew’s thorough research, I highly recommend that it be done. Writing as Jesse Rascoe, he collected much of the lore in Pegleg’s Lost Gold (Fort Davis, Texas: 1973). There are also articles about the story in several other Rascoe books. Given his life-long interest in lost treasure, it is no surprise that Ed saw fit to include “Peg Leg” Smith in his Western Hard-Cases; Or, Gunfighters Named Smith (Ruidoso, New Mexico: 1960), although Thomas L. Smith was not really a "gunfighter."

I enjoyed reading John Southworth’s Pegleg; To Date – And Beyond; Peglegiana Today. The Story, Its History and Recent Developments. How It Got That Way and Where it is Going [Privately printed by the Author: No Place: 1975]. The title certainly sums up the book. I think he did a good job of analyzing several claims to have found the source of the black gold nuggets.

Finally there is the remarkable Vengeance! The Saga of Poor Tom Cover by Dan L. Thrapp (El Segundo, California: 1989) Montana and the West Series VI. After a full and adventurous life, Tom Cover vanished in the Mojave Desert searching for the lost Pegleg Smith mine.

In fact where is any town of substance between Yuma and San Bernardino ? We See the Bradshaw trail, we see where today the I-10 goes to AZ, we see Dos Palmas station, and a little N a Indian Village and then... Nothing until San Bernardino, even Beaumont and Banning are not shown, but wouldn't there be someone to help out a straggler SOMEWHERE within these miles

In fact where is any town of substance between Yuma and San Bernardino ? We See the Bradshaw trail, we see where today the I-10 goes to AZ, we see Dos Palmas station, and a little N a Indian Village and then... Nothing until San Bernardino, even Beaumont and Banning are not shown, but wouldn't there be someone to help out a straggler SOMEWHERE within these miles