Corporate Investigations

Sr. Member

- Aug 23, 2013

- 468

- 1,437

- Primary Interest:

- All Treasure Hunting

Dreams of fortune and glory is not a new one and even after the conquest of the Incas people so dreamed of fortune and glory in Peru.

One such claim came from Paolo Greer's research in 1978.

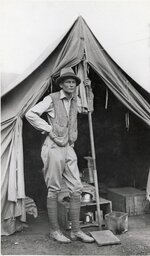

Greer posed the question was "lost city of the Incas", Machu Picchu, was it actually discovered forty years earlier than thought, and ransacked? Machu Picchu was famously discovered by Hiram Bingham in 1912. Greer claimed New evidence shows that it may have first visited in 1867 by an obscure German entrepreneur named Augusto Berns, who apparently looted the tombs with the Peruvian government's blessing.

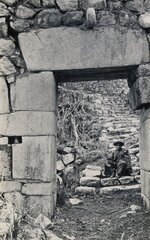

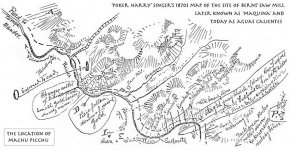

When Bingham arrived, he found a hut called "La Maquina". This was actually part of a sawmill which Berns ran in the area, after purchasing 25 kilometres of land along the Vilcanota River in 1867. He then realised the immense potential value of Machu Picchu's artefacts.

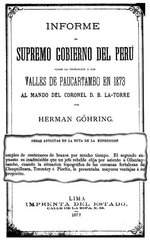

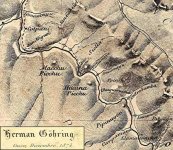

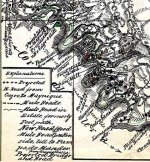

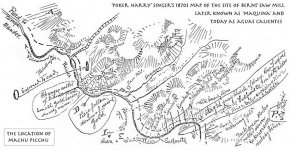

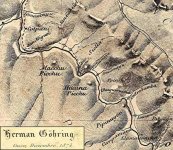

Berns' activities were uncovered by Paolo Greer, who in 1978 discovered an old map of the area and subsequently traced Berns' activities through documents in the National Library of Peru. Here below are some of the documents Greer uncovered, which you can see on the right. Greer uncovered a sketch map of the area by Berns' partner, a lost geology book with material based on Berns' work, a booklet describing Berns' plans to loot Machu Picchu, and his handmade map of the area.

Is there any truth in the story or is just another false claim in history?

Other historians claim Entrepreneur Augusto R. Berns was not the first man to promise treasure in the Andes, but he might have been the most fanciful. His 1881 prospectus – written while he was living in Detroit, Michigan – for the development of an alleged gold property in Peru’s Urubamba Valley, informed potential investors that the region was more like “the south of France more than any other” place on earth.

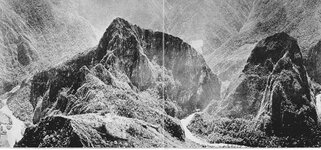

The property, “Torontoy or Cercada-de-San Antonio Estate in Southern Peru,” an 8-by-18 square-mile section of the valley, not only rivaled Provence, but also contained a stairway and paved road that ascended to certain ruins, which Berns extravagantly called “The Towns of the Gold and Silver Smiths of the Andes.” Was he refering to Machu Picchu?

Another auriferous trove on his land, “Llamajcansha,” Berns helpfully translated as “Gold Yard.” In reality, it means “Llama Yard.” Was Berns was selling his investors a load of llama dung?

All in all, Berns emphasized, “the WHOLE DISTRICT, generally, only requires to be known and opened up to be universally recognized as the greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world, and thus of immense value to any body of capitalists possessing really adequate means to profit by it in a MERCANTILE as well as mineral point of view.”

The enterprise would require the payment of a semi-annual $16 “mining License,” which would “entitle any proprietor to search for the precious metals or for hidden treasure (the last a common and sometimes lucrative occupation in Peru.)”

Berns was willing to sell the entire estate for $55,000 – more than a million dollars in today’s money – of which $30,000 was to pay off the mortgage, $15,000 to pay the claims of his former partners, and $10,000 to pay the expenses he had accrued. In other words, he was offering to sell what he had described as the “greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world” for nothing more than the amount of his outstanding debts.

But he set a high bar. His prospectus indicated that any buyer must be “a syndicate or company of bona fide capitalists,” willing to commit no less than $10 million – more than $200 million today – to the development of the property. The buyer must be agreeable to paying Berns $5,000 a year and, “as traveling is extremely expensive in Peru,” an additional $5,000 or more in annual travel expenses. In today’s money, that would be about $100,000 a year.

What became of the Torontoy scheme is not known. Today, some argue that Berns was referring to Machu Picchu, but the Torontoy property – assuming he even owned it – illustrated on his map was on the opposite side of the Urubamba River from Machu Picchu. In any event, there is no indication that any “bona fide capitalists” ever appeared at Berns’s door or that a single gold nugget was ever found.

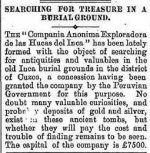

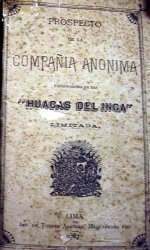

Several years later, now back in Peru, Berns launched another scheme, the “Compañía Anónima Exploradora de las ‘Huacas del Inca’ Limitada,” and recruited eminent Peruvians and foreign residents, including the British vice consul in Mollendo, as board members or agents. The company’s prospectus said that the government of Peru “has guaranteed the success of our enterprise.” Hardly. In 1888, one year after “Huacas del Inca” was organized, its vice-president resigned, charging that Berns had been using company funds for personal use and had failed to launch a single treasure-hunting expedition.

So you see the promised land of gold and treasure does also draw treasure hunters but as always like vultures waiting in the wings are con artists waiting to pounce of those wanting to dream. Was Berns a maligned treasure hunter or a con artist?

Corp

One such claim came from Paolo Greer's research in 1978.

Greer posed the question was "lost city of the Incas", Machu Picchu, was it actually discovered forty years earlier than thought, and ransacked? Machu Picchu was famously discovered by Hiram Bingham in 1912. Greer claimed New evidence shows that it may have first visited in 1867 by an obscure German entrepreneur named Augusto Berns, who apparently looted the tombs with the Peruvian government's blessing.

When Bingham arrived, he found a hut called "La Maquina". This was actually part of a sawmill which Berns ran in the area, after purchasing 25 kilometres of land along the Vilcanota River in 1867. He then realised the immense potential value of Machu Picchu's artefacts.

Berns' activities were uncovered by Paolo Greer, who in 1978 discovered an old map of the area and subsequently traced Berns' activities through documents in the National Library of Peru. Here below are some of the documents Greer uncovered, which you can see on the right. Greer uncovered a sketch map of the area by Berns' partner, a lost geology book with material based on Berns' work, a booklet describing Berns' plans to loot Machu Picchu, and his handmade map of the area.

Is there any truth in the story or is just another false claim in history?

Other historians claim Entrepreneur Augusto R. Berns was not the first man to promise treasure in the Andes, but he might have been the most fanciful. His 1881 prospectus – written while he was living in Detroit, Michigan – for the development of an alleged gold property in Peru’s Urubamba Valley, informed potential investors that the region was more like “the south of France more than any other” place on earth.

The property, “Torontoy or Cercada-de-San Antonio Estate in Southern Peru,” an 8-by-18 square-mile section of the valley, not only rivaled Provence, but also contained a stairway and paved road that ascended to certain ruins, which Berns extravagantly called “The Towns of the Gold and Silver Smiths of the Andes.” Was he refering to Machu Picchu?

Another auriferous trove on his land, “Llamajcansha,” Berns helpfully translated as “Gold Yard.” In reality, it means “Llama Yard.” Was Berns was selling his investors a load of llama dung?

All in all, Berns emphasized, “the WHOLE DISTRICT, generally, only requires to be known and opened up to be universally recognized as the greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world, and thus of immense value to any body of capitalists possessing really adequate means to profit by it in a MERCANTILE as well as mineral point of view.”

The enterprise would require the payment of a semi-annual $16 “mining License,” which would “entitle any proprietor to search for the precious metals or for hidden treasure (the last a common and sometimes lucrative occupation in Peru.)”

Berns was willing to sell the entire estate for $55,000 – more than a million dollars in today’s money – of which $30,000 was to pay off the mortgage, $15,000 to pay the claims of his former partners, and $10,000 to pay the expenses he had accrued. In other words, he was offering to sell what he had described as the “greatest gold and silver producing centre in the world” for nothing more than the amount of his outstanding debts.

But he set a high bar. His prospectus indicated that any buyer must be “a syndicate or company of bona fide capitalists,” willing to commit no less than $10 million – more than $200 million today – to the development of the property. The buyer must be agreeable to paying Berns $5,000 a year and, “as traveling is extremely expensive in Peru,” an additional $5,000 or more in annual travel expenses. In today’s money, that would be about $100,000 a year.

What became of the Torontoy scheme is not known. Today, some argue that Berns was referring to Machu Picchu, but the Torontoy property – assuming he even owned it – illustrated on his map was on the opposite side of the Urubamba River from Machu Picchu. In any event, there is no indication that any “bona fide capitalists” ever appeared at Berns’s door or that a single gold nugget was ever found.

Several years later, now back in Peru, Berns launched another scheme, the “Compañía Anónima Exploradora de las ‘Huacas del Inca’ Limitada,” and recruited eminent Peruvians and foreign residents, including the British vice consul in Mollendo, as board members or agents. The company’s prospectus said that the government of Peru “has guaranteed the success of our enterprise.” Hardly. In 1888, one year after “Huacas del Inca” was organized, its vice-president resigned, charging that Berns had been using company funds for personal use and had failed to launch a single treasure-hunting expedition.

So you see the promised land of gold and treasure does also draw treasure hunters but as always like vultures waiting in the wings are con artists waiting to pounce of those wanting to dream. Was Berns a maligned treasure hunter or a con artist?

Corp