Battlefield Archeology at Kings Mountain National Military Park, South Carolina

Although portable metal detectors have been used recreationally since the development of the equipment in the mid-1940s, little common ground had been established between archeologists and metal detecting hobbyists. It would have likely continued this way if not for a wildfire in 1984 that consumed the tall grass covering the Little Big Horn Battlefield in Little Bighorn Battlefield NM in eastern Montana. The fire provided a unique opportunity for an innovative archeologist and a group of metal detector hobbyists to establish a mutually beneficial working relationship that resulted in the collection of valuable data about the 130 year old battle. This collaboration on the plains of Montana provided the basis for a whole new line of inquiry which came to be known as Battlefield Archeology. Projects undertaken on battlefields in the Southeast United States by staff of the NPS Southeast Archeological Center employed, modified, and improved battlefield archeology methods to provide new and/or revised interpretations of battles associated with the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Indian Wars, and the Civil War.

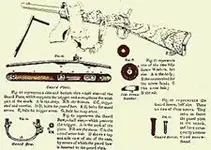

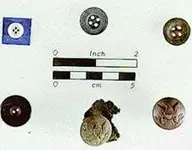

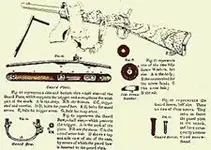

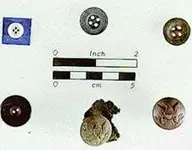

Various artifacts from the Revolutionary War surveys (NPS photo)

Various artifacts from the Revolutionary War surveys (NPS photo)

While the first working metal detectors were invented in the mid-1830s, and even used by Alexander Graham Bell to search for the assassin’s bullet in an American president, the hobby did not truly begin until the end of World War II (Roberts 1999). The demands for bomb detectors during the war led to the production of large numbers of metal detectors, which were later sold as surplus. The post war economic boom infused Americans with a new enthusiasm for leisure activities, including metal detecting. The hobby of metal detecting did not explode until the 1970s, after the introduction of the microprocessor, printed circuit board, and miniaturized transistors. These innovations reduced the price and weight of metal detectors, making them more accessible to the public. However, their usefulness as a tool for archeological inquiry was met with skepticism which extended to metal detecting hobbyists as well (Scott 2005).

Archeologists have been using metal detectors for as long as the machines have been available. Unfortunately during much of this time the machines and operators have not been effective for archeological pursuits. With few exceptions, the results were so poor that it led to the conclusion that a metal detector in the hands of an archeologist was the same as doing nothing at all. In many cases, archeologists only located large targets and then dismissed the machines as ineffective, never realizing that they were repeating a pattern common in novice metal detector users. Novice users, which include many archeologists, tend to locate larger targets, and to miss bullets and other battle related items.

As a result, many archeologists dropped metal detectors as an archeological data collection technique. Other archeologists felt that use of metal detectors would link them with looters who use them in the eyes of the public, and weaken arguments against allowing open detecting on federal lands.

Metal-Detecting and Battlefield Archeology

The most accurate data results from the proficient use of this technology by individuals who can effectively employ and interpret this technology, the number of successes has grown as archeologists developed an appropriate methodology. In 1972, when Snow (1981) demonstrated the archeological data potential of battlefield archeology at the Saratoga Battlefield in Saratoga National Historic Park, a Revolutionary War period site dating to 1777, in upstate New York. Snow discarded traditional archeological techniques and chose instead to use aerial photographs, magnetometers, and soil probes to locate battlefield positions. Although he did not employ metal detecting, his work clearly showed that there was an enormous historical and cultural data potential in American battlefields. This served to enhance the value of such studies and set the stage for the use of metal detecting as an archeological research tool.

A year after Snow's pioneering work, Dickens (1979) conducted an archeological investigation at Horseshoe Bend National Military Park in eastern Alabama that included a systematic sweep using metal detectors. This was the site of a battle that took place between the US Army and the Upper Creek Indian Confederation in March 1814. During the survey, eleven artifacts that related to the battle were recovered. These include “…lead rifle balls, three iron grape shot, and two iron-cut nails” (Dickens 1979:26). This study demonstrated that acceptable results could be obtained using metal detectors. The archeological literature is virtually devoid of successful metal detecting surveys on battlefields for the decade following Dickens' work, however.

Arguably, the most important archeological metal detecting took place in 1984, at Little Bighorn Battlefield in eastern Montana. This is the site of a battle that took place between the US Army and Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne forces in 1876. During this survey Scott and Fox showed the effectiveness of working with metal detectors and metal detecting hobbyists to obtain information about battlefields (Scott and Fox 1987). Based on the results of their testing (Fox and Scott 1991) the researchers later described a post-Civil War battlefield pattern. The identification of a pattern began with the determination of individual actions identified from the distribution of artifacts with unique signatures or characteristics (e.g., rifling patterns on bullets, ejector marks, or firing pin marks). The individual patterns were aggregated into unit patterns, which in turn formed the battlefield pattern. Fox and Scott described battlefield patterns as “in the absence of unit tactical disorganization, signature patterning may reflect prescribed deployment” (1991:97).

While Scott and Fox (1987) worked on a battlefield where each side had different weapon types, this was not true of most of the other conflicts that have taken place in the southeastern U.S. One method used to compensate for the lack of unique bullet signatures was illustrated by Lees (1992). His study of the Mine Creek Battlefield in eastern Kansas led him to conclude that clusters of "unfired” or "dropped" bullets provide the best basis for reconstructing troop positions, because they mark the precise location of individuals. Concentrations of fired bullets falling behind unit positions, on the other hand, are most likely indirect indicators of lines, and thus these represent a "ghost" of those positions (Lees 1992:8).

Between 1992 and 1993, Haecker and Mauck (1997) conducted research at Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site in southeast Texas, the site of the first battle of the Mexican War (1846-1848). This research showed the effectiveness of using historic maps in conjunction with geographic information systems (GIS) to guide the archeological testing.

Beginning in 1992 and continuing until the present, the NPS Southeast Archeological Center (SEAC) has been conducting battlefield surveys using metal detector hobbyists. During that time methodological innovations have continued. These innovations include aggregating data into cells and producing contour maps of battle activity, creating a stability index for individual battle areas (Cornelison 2006a), using Sivilich’s (1996) shot calculation formula in conjunction with GIS maps to interpret battlefields (Cornelison and Cooper 2002a), and the application of multiple technologies on battlefield sites (Cornelison and Cooper 2002b).

At SEAC, the relationship between archeologists and metal detector hobbyists began in 1992. The Chattanooga Area Relic and Historical Association (CARHA), a local group of metal detecting hobbyists approached the historian at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park to offer assistance with the park’s battlefield survey. Fortuitously SEAC had just acquired an electronic total station and needed to field test the equipment. The project took place at Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, which is located in northwest Georgia and southeastern Tennessee, is the site of a Civil War battle that took place in September 1863.

An area inside the western edge of the Chickamauga Battlefield, slated for highway development, was selected as a test location for the transit and the metal detecting survey. This area had been previously surveyed using both metal detecting and shovel testing by an archeologist and had found no significant archeological resources. The survey was conducted between 1992 and 1993. The CARHA members were overwhelmingly hard-working and knowledgeable. The metal detecting teams located artifacts from the battle that conventional survey methods and archeologists’ use of metal-detectors had missed.

The 1992 work at Chickamauga and Chattanooga NMP demonstrated the usefulness of metal detecting as a research tool but more importantly it demonstrated that experience with the equipment made a significant difference in what was located and recovered and that a working relationship between archeologists and metal detecting hobbyists was not only possible but important to achieving reliable results. The SEAC has undertaken archeological survey using volunteer metal detector on five American Civil War parks (Cornelison 2000, 2005, 2007), on three Revolutionary War battlefields (Cornelison 2006b, Cornelison and Cooper 2002a, Cornelison and Groh 2007), on one Red Stick (Indian) battlefield (Cornelison 2006b), and one War of 1812 battlefield (Cornelison and Cooper 2002b). The following discussion of a Revolutionary War battlefield survey illustrates the results that can be obtained when there is a good relationship between archeologists and metal detector hobbyists.

The Battle of Kings Mountain - Revolutionary War, October 1780

Historical Account

The Battle of Kings Mountain was fought on October 7, 1780, in the northern part of the South Carolina colony. British Colonel Patrick Ferguson was in the area to recruit a militia force to aid the British cause. Ferguson was quite successful at raising the troops, but some of his actions had inflamed the Patriot Overmountain men from the western part of the state. Overmountain men were Patriots in eastern Tennessee and Southwestern Virginia.

When apprised of Ferguson’s activities, Patriot Militia Colonels Isaac Shelby, John Sevier, William Campbell, Charles McDowell, and Andrew Hampton conferred and decided to attack the Loyalist militia. These troops were met by Militia Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and Joseph Winston, whose troops increased the total to about 1400. They tracked Ferguson’s similar-sized force to Kings Mountain, where the British were camped along a large ridge, now known as Battle Ridge.

The Overmountain men encircled the base of the ridge and then began to fight up the slopes. The Loyalists’ British-supplied muskets, firing down slope, could not match the accuracy of the Patriots’ rifles being fired uphill. Once the Patriots made the summit of the ridge, the Loyalists were driven back to the east end of the ridge. After a bloody fight lasting less than 2 hours, some of the Loyalists were allowed to surrender. Ferguson attempted to escape and was shot dead. The battle, the death of Ferguson, and the harsh treatment of the Loyalists following the battle including hangings, effectively ended British recruiting of American militia (Blythe et al. 1995, Draper 1971).

Survey, Results, and Interpretation

Today, Kings Mountain Battlefield in located in

Kings Mountain NMP. The survey of the battlefield took place over two field seasons and almost 300 volunteer hours were logged. All total, some 90 acres were surveyed by metal detecting. During the survey, 139 Revolutionary War period artifacts were recovered, including 81 fired and 54 unfired lead shot from the battle. The locations of these rounds clearly show the location of the assaults up Kings Mountain.

The artifacts formed five clusters. The first cluster is located on the southwest end of the ridge. At the time of the survey this area was not considered to be part of the battlefield. Using the most accepted interpretation of troop positions, this southwest cluster represents Sevier’s assault (Draper 1971). Continuing northeast up the ridge, another cluster is located to the north. This cluster represents the assault of Shelby’s men. These two areas are gentle slopes where the top of the ridge can be mounted without much difficulty. It is logical to assume that the assaulting Patriot force would take the easiest route up the ridge and, in fact, the physical evidence bore this out.

The next cluster to the northeast is a linear cluster that runs on the south slope of the ridge. This cluster, consisting of many fired and few dropped shots, represents the firing of McDowell’s men on the unfortunate Loyalists. It is a hard climb to the top of the ridge from this side and would be hard to do under fire. The saddle of the ridge is virtually devoid of shot. This illustrates that once the western end was taken the Loyalists fled to the east end of the ridge and made their stand.

The forth cluster is important not for what was found but for what was not found. The flat area of the ridge was the presumed site of the location of Ferguson’s wagons. While some shot was collected in this area, no evidence of the wagons or their burning was encountered.

The final cluster, located on the eastern end of the ridge, shows the closing of the vise. The troops of Campbell, Cleveland, Chronicle, and Winston put pressure on the Loyalists as they clung to the top of the ridge. The absence of shot in the saddle shows that, as tactical stability broke down, there was a quick movement by the Loyalists along the ridge as they sought the perceived safety of those on the eastern end of the ridge (Draper 1971).

The results of this joint project between metal detecting hobbyists and archeologists show the benefits of such cooperation. The data derived from identification of metal objects from the metal-detecting was more accurate and more complete than previously known, giving a more accurate understanding of the battle.

Conclusions

This project clearly shows the level of information collection possible using a group of dedicated volunteer metal detector hobbyists. Without the metal detector hobbyists volunteering their time, none of the new information about the Kings Mountain battle would be available to the public. The relationship has been one of mutual benefit, as volunteers are able to work in places to which they would not otherwise have access and they can handle and photograph the artifacts found. This gives them “bragging rights” and additional information about material culture.

The archeologists, on the other hand, have a cadre of hard working volunteers. The volunteers are knowledgeable about the material culture and each individual is an important resource. They are willing to travel great distances, sometime at personal expense, to participate in the fieldwork. In short, park archeologists would be unable to do this work without the skills that these volunteers bring.

John E. Cornelison Jr. and George S. Smith, Southeast Archeological Center

NPS Archeology Program: Research in the Parks

Because I could easily have flagged 100 such signals, of which 99% were going to be modern cr*p.

Because I could easily have flagged 100 such signals, of which 99% were going to be modern cr*p.